Attention freeway builders! Want to make up for dividing the community and destroying neighborhoods? How about replacing the homes you demolished?

One of the carefully crafted talking points in the sales pitch for the $450 million proposed Rose Quarter I-5 freeway widening project in Northeast Portland is the idea that it is somehow going to repair the damage to a community split asunder by a combination of road building and urban renewal in the 1960s. The Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) has created the illusion that the slightly widened freeway overpasses its building will be aesthetic “covers” that will somehow knit the neighborhood–historic center of the region’s African-American community–back together.

And political leaders have jumped on the bandwagon to make this point.

Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler went so far as claiming that the project,

“. . . restores the very neighborhood that was the most impacted by the development of I-5 and that’s the historic African American Albina community.”

And also following up in an interview:

One of the parts of this that nobody talks about, that frankly is the most interesting to me, is capping I-5 and reconnecting the street grid for the historic Albina community. And that of course is mostly a bicycle and pedestrian play. So I think this is being mischaracterized somewhat when people say, ‘Oh this is just a freeway expansion and it’s never going to meet its goals of congestion reduction.’ This is far from just focusing on just congestion reduction, this is an opportunity to restore one of our most historic — and not coincidentally — African American neighborhoods in this community.

City Commissioner Dan Saltzman added:

These new, seismically upgraded bridges will provide better street connections, improved pedestrian and bicycle facilities, a new pedestrian and bicycle-only bridge as well as lids (or covers) of the freeway that can provide much needed community space.ODOT is selling the project as a way of fixing the damage the freeway did to the area.

Public Policy and Community Affairs Manager Shelli Romero talked up the agency’s “environmental and public process” which will include:

“. . . a robust understanding, research and engagement strategy of the historically wronged African-American community and other communities of color. We understand the historic inequity concerns and will engage all communities in this project,” Romero promised.

Noble sentiments to be sure. But in our view this project does nothing to right the wrongs of freeway construction. Despite the high-minded rhetoric, widening the freeway repeats the same errors made a half-century ago and make the neighborhood’s livability worse. If these leaders are serious about redressing the historical wrongs done here, they could do much better.

The freeway and the damage done

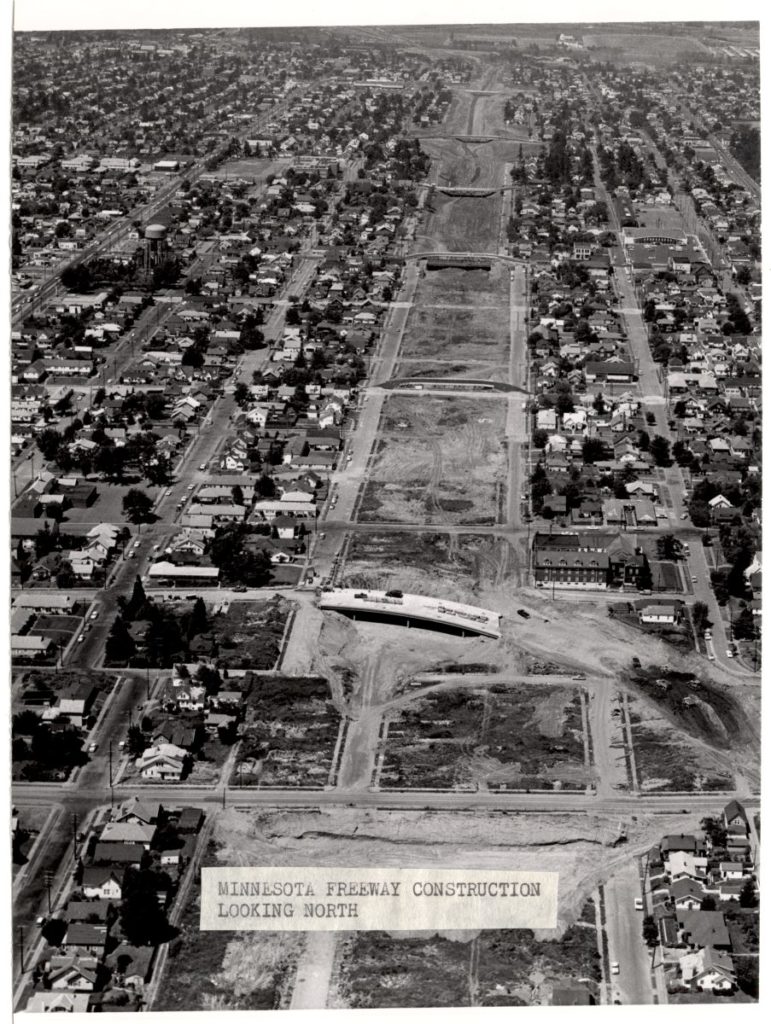

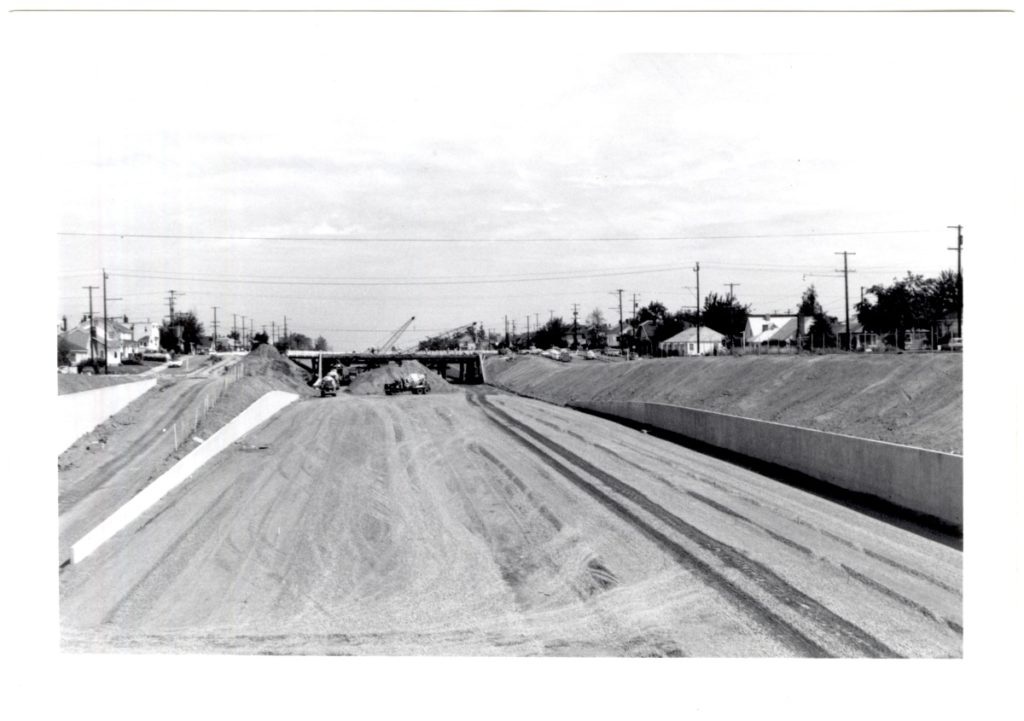

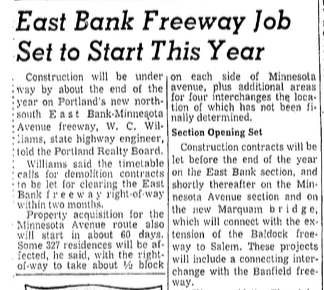

But let’s step back for a minute and look at what the construction of the Rose Quarter Freeway did to the North and Northeast Portland neighborhoods is slashed through in the 1960s. Originally, I-5 was called the Minnesota Freeway, not because it led to that state, but because it followed the route of Minnesota Avenue. A few vestiges of that street remain, but mostly, I-5 runs in a trench that was excavated right down the middle of the former Minnesota Avenue (in some places also wiping out parts of the adjacent Missouri Avenue. The freeway runs for 3 miles from Broadway to just north of Lombard Street. In that stretch of road, the city also ended up dead-ending some 25 East-West cross streets. The southern portion of the route passed through the historically African-American neighborhoods of Albina.

When it built the freeway, the city condemned or purchased hundreds of homes in the neighborhood. We haven’t been able to locate any official Oregon State Highway Department records, but contemporary press accounts say at least 327 homes were demolished for the freeway.

The highway department paid as little as $50 for homes, and because it judged that there were a sufficient number of vacant units in the region, it didn’t build any replacement housing. (Decades later, the highway builders did construct concrete sound walls to buffer the adjacent neighborhoods from the freeway noise.) The City of Portland tried to find money to help offset the displacement, but was barred from using urban renewal funds for the project. There’s no evidence the Oregon State Highway Department replaced even one of the more than 300 homes it demolished.

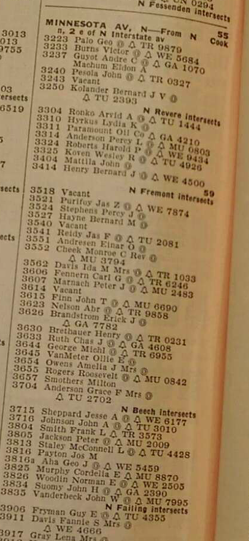

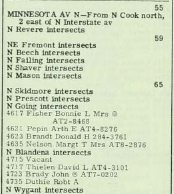

It’s now mostly lost to memory, but real people were displaced by freeway construction. We can get a glimpse of their presence and identity by looking at the City Directory for N. Minnesota Avenue for 1958, which lists the names and house numbers of all the families living along the street. George Palo, Victor Burns, Andre Guyot, Eldon Methum, John Pesola, Bernard Kolander, Arvid Renko, Lydia Kyrkus, Perry Anderson, Harold Roberts, Wesley Koven, John Mattila, Bernard Henry, Percy Stevens, Ida Davis, Reverend Monroe Cheek, and hundreds of others were living on Minnesota Avenue.

Just four years later all these people were gone. The 1962 City Directory contains a blank spot where these houses and their hundreds of Portland residents had lived. Not a single building or resident remained on the blocks between N. Cook Street and N. Going Street.

With hundreds fewer homes and residents, there were fewer customers for local businesses, fewer students for local schools, and less property tax revenue to pay for public services. The quality and health of this neighborhood was sacrificed to speed through traffic and facilitate increasing suburban car commuters. The freeway had other effects on the neighborhood. It bisected the attendance area for the Ockley Green Elementary School, meaning many students could no longer easily walk to school. Several local neighborhood streets were transformed into busy, high speed off ramps. In the planning process, local officials raised these concerns with the state highway department, and were offered assurances that “every effort” would be made to solve these problems. The words spoken by highway department officials then sound almost identical to the assurances offered by ODOT spokesmen in response to concerns raised today about the Rose Quarter project. University of Oregon historian Henry Fackler describes the 1961 meeting convened by the city to address the effects of street closures:

At the meeting’s conclusion, state engineer Edwards assured those in attendance that “every attempt will be made to solve these problems.” The freeway opened to traffic in December 1963. No changes were made to the route.

As part of today’s Rose Quarter freeway widening process, ODOT is holding similar meetings to the ones it held 55 years ago. When the Cascadia Times recently tried to follow up on concerns about construction and air quality impacts of the proposed freeway widening project on local schools, and was given a similar vague reassurance:

ODOT declined to make Johnson or Braibish available for comment. But spokesperson Don Hamilton pointed out that any ODOT construction is several years out, and that planning is in a very preliminary stage. He noted that PPS [Portland Public Schools] is moving on a different time frame than ODOT, but that when all is said and done, “We’ll work with them to make sure their needs are met …”

A tale of two agencies

Public leaders have acknowledged that freeway building and urban renewal devastated neighborhoods in Portland (and in cities around the US). It’s one thing to acknowledge a past transgression, but the sincerity of that admission is measurable by whether there’s any actual willingness to repair the damage done.

In recent years, the Portland Development Commission (now Prosper Portland) has publicly acknowledged the role its urban renewal programs played in undermining North and Northeast Portland neighborhoods. Its dedicated a substantial portion of its tax increment financing moneys in the area to building new housing. The city even has a program to identify households displaced from the neighborhood by urban renewal, and give them preferential access to newly constructed subsidized housing.

In contrast, the Oregon Department of Transportation is proposing to double down on the scar it carved through the neighborhood. Its proposal widens the freeway. Despite talking points to the contrary, three key design features of the project show that the agency has the same old indifference to its impacts on the neighborhood. First, the widening project will run theeven closer to Harriet Tubman Middle School, so close, in fact that construction may undermine part of the building’s foundations, and worsen air quality. The Portland school district is contemplating a million dollar proposal for a wall and vegetation to shield the school from existing freeway emissions. Second, as we’ve discussed at City Observatory, the project will demolish the nearby Flint Avenue Bridge, a key low-speed, bike-friendly neighborhood street that crosses the freeway. Third, the project re-arranges the local streets connecting to the freeway into a miniature “diverging diamond” interchange, designed to speed car traffic, but creating a hostile and dangerous situation for pedestrians. Far from righting historical wrongs, ODOT is embarked on an expensive plan to repeat them, and inflict further damage on this neighborhood.

What ODOT should do: Build housing

If it really wants to make amends for the extensive damage freeway building did to North and Northeast Portland, and fulfill Mayor Wheeler’s pledge of “restoring” the neighborhood, a good place to start would be by replacing the housing demolished to build the Minnesota Freeway in the 1960s. The average price of single family homes adjacent to the freeway (which is no doubt negatively affected by noise and air pollution) is about $424,000. If ODOT were to build 330 or so homes to replace those lost in the 60s, the total cost would be approximately $140 million.

It’s worth keeping in mind that for the past 50 years, Portland has been negatively affected by the loss of that housing. Not only were its original residents displaced, but the loss of that housing meant fewer options for people who wanted to live in that neighborhood, fewer students at local schools, fewer customers for local businesses, and less property tax revenue for the city and schools. More housing in this neighborhood would come at a propitious moment: helping alleviate a housing shortage, and providing more opportunities to live in one of the region’s most walkable, bike-friendly locations.

This freeway slashed through Portland neighborhoods, destroyed housing, and displaced families. Widening that freeway–at the cost of half a billion dollars–does nothing to right that wrong. It actually repeats the same mistake. If it’s serious about fixing the damage it’s done, it could do something very different and meaningful: build homes.

This post has been revised to correct identify Missouri Avenue as the other street affected by freeway construction, and to correct formatting errors in the originally published version.