Last month, we took exception to critics of Detroit’s economic rebound who argued that it was a failure because the job and population growth that the city has enjoyed has only reached a few neighborhoods, chiefly those in and around the downtown. A key part of our position was that successful development needs to achieve critical mass in a few locations because there are positive spillover effects at the neighborhood level. One additional house in each of 50 scattered neighborhoods will not have the mutually reinforcing effect of building 50 houses in one neighborhood. Similarly, building new housing, a grocery store, and offices in a single neighborhood makes them all more successful than they would be if they were spread out among different neighborhoods. What appears to some as “unequal” development is actually the only way that revitalization is likely to take hold in a disinvested city like Detroit. That’s why we wrote:

. . . development and city economies are highly dependent on spatial spillovers. Neighborhoods rebound by reaching a critical mass of residents, stores, job opportunities and amenities. The synergy of these actions in specific places is mutually self-reinforcing and leads to further growth. If growth were evenly spread over the entire city, no neighborhood would benefit from these spillovers. And make no mistake, this kind of spillover or interaction is fundamental to urban economics; it is what unifies the stories of city success from Jane Jacobs to Ed Glaser. Without a minimum amount of density in specific places, the urban economy can’t flourish. Detroit’s rebound will happen by recording some small successes in some places and then building outward and upward from these, not gradually raising the level of every part of the city.

While this idea of agglomeration economies is implicit in much of urban economics, and while the principle is well-understood, its sometimes difficult to see how it plays out in particular places. A new research paper prepared by economists Raymond Owens and Pierre-Daniel Sarte of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and Esteban Rossi-Hansberg of Princeton University tries to explore exactly this issue in the city of Detroit. If you don’t want to read the entire paper, CityLab’s Tanvi Misra has a nice non-technical synopsis of the article here.

The important economic insight here is the issue of externalities: In this case, the success of any persons investment in a new house or business depends not just on what they do, but whether other households and businesses invest in the same area. If a critical mass of people all build or fix up new houses in a particular neighborhood (and/or start businesses) they’ll benefit from the spillover effects of their neighbors. If they invest–and others don’t–they won’t get the benefit of these spillovers.

Analytically this produces some important indeterminacy in possible outcomes. Multiple different equilibria are possible depending on whether enough people, businesses, developers and investment all “leap” into a neighborhood at a particular time. So whether and how fast redevelopment occurs is likely to be a coordination problem.

Without coordination among developers and residents Owens, Rossi-Hansberg and Sarte argue, some neighborhoods that arguably have the necessary fundamentals to rebound won’t take off. Immediately adjacent to downtown Detroit, for example, there are hundreds of acres of vacant land that offer greater proximity to downtown jobs and amenities than other places. Why, the authors ask, “do residential developers not move into these areas and develop residential communities where downtown workers can live?”

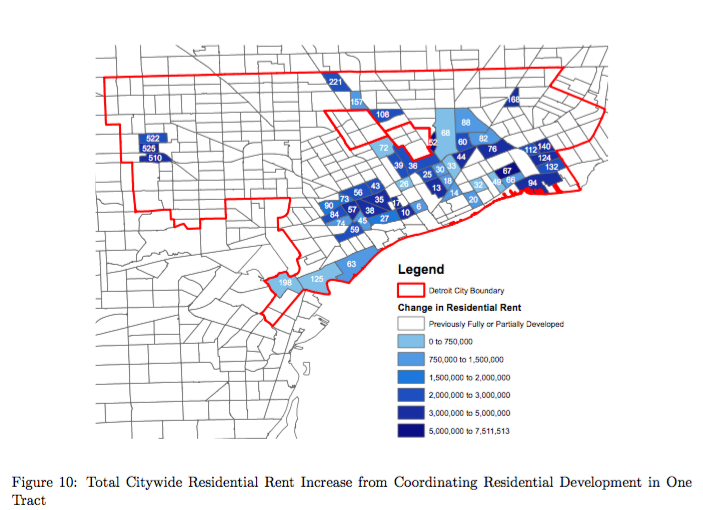

The authors measure the potential for future growth by estimating the total increase in rents associated with additional housing development and population growth in each neighborhood. Some neighborhoods are well-positioned for development to take-off, and would show the biggest gains in activity, if the coordination problem could be overcome. That coordination problem is apparent in neighborhoods near downtown Detroit: even though it would make sense to invest, no one wants to be the first investor, for fear that other’s won’t invest. So Owens, Rossi-Hansberg and Sarte suggest this obstacle might be overcome if we could create a kind of “investment insurance”–if you invest in this neighborhood, then we’ guarantee a return on your home or business.

As a thought experiment, the authors estimate the amount of a development guarantee that would be needed to trigger a minimum level of investment needed to get a neighborhood moving toward its rebuilding. In theory, offering developers a financial guarantee that their development would be successful could get them to invest in places they wouldn’t choose to invest today. That investment, in turn, would trigger a kind of positive feedback effect that would generate additional development, and the neighborhood would break out of its low-development equilibrium. If the author’s estimates are correct, its unlikely that the guarantees would actually need to be paid.

While this concept appears sound in theory, much depends on getting the estimates right, and also on figuring out how to construct a system of guarantees that doesn’t create its own incentive problems. In effect, however, this paper should lend some support to those in Detroit who are attempting to make intensive, coordinated investments in a few neighborhoods.

More broadly, this paper reminds us of the salience of stigma to neighborhood development. Once a neighborhood acquires a reputation in the collective local consciousness for being a place that is risky, declining, crime-ridden or unattractive, it may be difficult or impossible to get a first-mover to take the necessary investment that could turn things around. The collective action problem is that no one individual will move ahead with investment because they fear (rationally) that others won’t, based on an area’s reputation. A big part of overcoming this is some action that changes a neighborhood’s reputation and people’s expectations, so that they’re willing to undertake investment, which then becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. While economists tend to think that the only important guarantees are financial , there are other ways that city leaders could actively work to change a neighborhood’s reputation and outlook and give potential residents and investors some assurance that they won’t be alone if they are among the first to move. New investments, for example, like the city’s light rail system, may represent a signal that risks are now lower in the area’s it serves than they have been.