La-La Land voters deal a crushing defeat to a “NIMBYism on steroids”

The latest returns show Los Angeles’ Measure S–the self-styled “Neighborhood Integrity Initiative”–failing by a 31 percent “Yes” to 69 percent “No” margin. If it had passed, Measure S was predicted to bring new housing development in Los Angeles to a screeching halt for the next two years, and probably longer.

This was a landslide vote against one of the most NIMBY ballot measures we’ve ever seen. And strikingly, it came under a set of circumstances that should have greatly favored the NIMBY cause. The proponents of the ballot measure cleverly chose to place it on the March local election ballot, rather than on last November’s general election ballot. Not only is turnout in local elections much lower (it was an estimated 13 percent of registered voters in Los Angeles yesterday*, compared to about 74 percent in the Presidential election), but the demographics of the local election voters skew much more heavily to older, whiter voters, and importantly to homeowners.

For a long time, the “homevoter” theory has held that restrictive local zoning regulations represent profit-maximizing behavior by local homeowners. Restricting the supply of new housing in your neighborhood, the argument goes, not only means that there are more free-curb parking spaces, but the value of your home increases.

While that logic holds strongly at the neighborhood level, the defeat of Measure S signals that at a larger level (and Los Angeles is a city of 3.9 million residents) it’s possible–just possible–for people to recognize that the policies that might make a neighborhood more livable or valuable, only result in higher rents and displacement when applied to a larger geography. Opponents of Measure S argued that it would have blocked new development, aggravating the region’s housing shortage and further driving up rents. Apparently their arguments were successful, even with this very much smaller segment of the electorate who ought to have been more pre-disposed to accept the NIMBY arguments. Like the 2015 rejection of a proposal in Boulder, Colorado, to allow a neighborhood level veto of new development, there’s growing public support for policies that enable housing supply to increase. This also tends to confirm the logic that if we make land use decisions at larger geographic levels (city-wide, rather than by neighborhood), we tend to get results that are more inclusive.

It’s too early to call this a turning point, but the strong rejection of this measure in a setting that should have maximized the chances of NIMBY success is a hopeful sign that American’s are recognizing that we have a shortage of cities, and that our affordability problems are a manifestation of the need to accommodate the growing demand for urban living. Who knows, maybe we can actually talk about “supply and demand” in the context of housing markets, and voters will respond.

What Measure S would have done

While nominally aimed at correcting the supposed abuses of the city’s re-zoning process–it’s common for many new developments to have to seek rezoning to move forward–the effect of Measure S provisions would have been much more sweeping. The proponents of Measure S made a lot of political hay by pointing out how out-dated and broken the city’s land use plans have become. Most of the city’s neighborhood plans are hopelessly out of date, and as a result, most sizable new developments require separate city council approval of plan amendments to move forward. To be sure, this is a political process, where the City Council gets to flex its muscles, and look out for the interests of citizens and constituents on a case-by-case basis. And when new development does move forward, there’s always the implication that developers curried political favor to get approval. The Yes on Yes on Measure S campaign made this a key talking point:

“Yes on Measure S released today a special report of official city information that reveals how L.A. City Hall works behind closed doors, on behalf of developers and usually without the knowledge of the public, to get around the city’s zoning rules. Most developers donate to L.A. elected leaders throughout the backroom process”

Nominally, Measure S would have called a time out–in the form of a two-year moratorium on most spot-zoning type plan amendments–until such time as full neighborhood plans are up dated. But the measure would have done more than that. Others have already offered up keen analyses of the flaws in Measure S. Planetizen’s Reuben Duarte explains that the Measure’s requirement that comprehensive plan amendments involve not less than 15 acres, and that they may not allow an increase in overall density:

More ominously, and less discussed than the moratorium, Measure S amends Los Angeles’ Charter to require all future potential general plan amendments meet a minimum threshold of 15 acres, and require all future plan updates to limit increases in density based on the existing average density of the planning area.

An impressive group of Los Angeles based academicians excoriated Measure S as likely to lead to increased sprawl and traffic, to worsen the city’s affordability problems, and make it harder for the children and grandchildren of today’s Angelenos to live in the city.

Measure S wouldn’t have made Los Angeles any less desirable as a place to live, but it will surely would have made it much harder to build new housing. As we’ve seen in cities around the country, the combination of rising demand and fixed supply has the fully predictable effect of driving up rents and making housing less affordable. Had it passed, it seems like a near certainty that Measure S would have made the plight of Los Angeles renters even worse.

California is one state where ballot box zoning has become increasingly common. In San Francisco, voters have decided height limits for individual projects. Voters in Davis cast up or down votes on subdivisions. These initiatives have made it difficult, expensive and highly uncertain for new development to move forward, limiting the growth in housing supplies and driving up rents.

Who votes in local elections

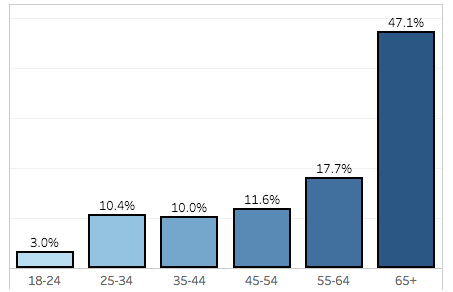

The defeat of Measure S is all the more surprising, because of the sponsor’s decision to place it on the March municipal election ballot, rather than last fall’s general election ballot. Not only was turnout in yesterday’s municipal election dramatically lower, it skewed heavily toward older, whiter voters and homeowners, the heart of the NIMBY constituency. As our friends at Portland State University have shown, the electorate in local elections is, on average, a generation older than those voting in general elections. Los Angeles has just shy of 2 million registered voters. In last November’s general election, about 58 percent of them (1.1 million) made it far enough down the ballot to vote on city measure JJJ, an affordable housing measure (it passed 65 percent to 35 percent). But in yesterday’s election, it looks like total voter turnout will be something like 13 percent.

While we won’t have final data on turnout for a few more days, the data on the characteristics of early voters clearly suggested this election was headed in an ominously NIMBY-leaning direction. In Los Angeles, more than 40 percent of registered voters received their ballots in advance. As of March 6, about 117,000 ballots had been returned. The election consulting firm Political Data, Inc, tracks these ballot returns. They reported than about 47 percent of the ballots were cast by those 65 or older (who represent about 20 percent of registered voters), and only 13 percent were cast by those 34 and younger (who constitute 34 percent of those registered. The firm also estimates turnout by homeowners and renters. While homeowners make up about 48 percent of those sent ballots in advance, they represented fully 60 percent of the ballots returned as of March 6. (Hat tip to Jordan Fraade for pointing us to this excellent data).

* – As of Wednesday March 8, about 250,000 ballots had been tabulated from about 2 million registered Los Angeles voters. In California, voters who receive vote by mail ballots have to have the ballots post-marked not later than election day, and received by the election office not later than three days after the election. Some additional vote-by-mail ballots will come in during the next few days and increase the turnout slightly.