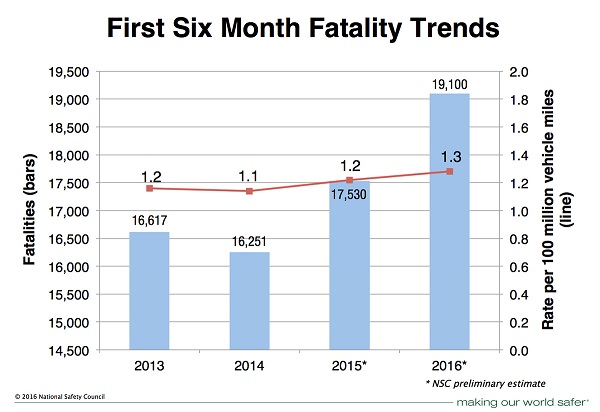

More grim statistics from the National Safety Council: The number of persons fatally injured in traffic crashes in the first half of 2016 grew by 9 percent. That means we’re on track to see more than 38,000 persons die on the road in 2016, an increase of more than 5,000 from levels recorded just two years ago.

Just two weeks ago, we wrote about the traditional summer driving season as a harbinger of the connection between the amount of driving we do and the high crash and fatality rates we experience. And these data show, for the first half of the year, that things are not going well. As alarming as these statistics are, the bigger question that they pose is why are crash rates rising? And what, if anything can we do about it?

It’s not the economy, stupid.

There are undoubtedly many factors at work behind the rise in crashes and crash deaths. There’s clearly much more we can do to make our city streets and roadways safer for all travelers.

We have to disagree with the National Safety Council on one key point: we shouldn’t mindlessly blame the economy for our safety woes. In their press release, they attribute the increase in fatalities to an improving economy, saying:

That’s an unfortunate, and probably incorrect framing, in our view. Chalking the rise in traffic deaths up to an improving economy seems a bit fatalistic: implying that more traffic deaths are an sad but inevitable consequence of economic growth, one which might prompt some people to shrug off the increase in deaths. That would be tragically wrong, because, at least through 2013, the nation experienced a decrease in traffic deaths and an improving economy.

What has changed, since 2014, is not the pace of job growth or the steady decline in the unemployment rate (both of which have been proceeding nicely since the economy bottomed out in 2009), but rather a reversal of the increase in gasoline prices which started in the summer of 2014. As we pointed out a few weeks ago, gas prices have been steadily declining, and as a direct result, Americans have begun driving more.

Now it would be fair to point out that a three percent increase in driving has been accompanied by a nine percent increase in traffic deaths. But we have good reasons to believe that the additional driving (and additional drivers and additional trips) that are prompted by cheaper gasoline are exactly the the ones that involve some of the highest risks. A study of gas prices and crash rates found that the relationship was indeed “non-linear”–that small changes in gas prices were associated with disproportionately larger increases in crash rates.

Higher gas prices not only discourage driving generally, they seem to have the effect of reducing risky driving, and thus produce a safety dividend. Its time to do more than just lament tragic statistics: if we want to make any progress toward Vision Zero, we ought to be putting in place policies that bring the price of driving closer to the costs that it imposes on society. If people reduce their driving–as they did when gasoline cost more than it does today–there will be fewer crashes and fewer deaths.