For many, it’s all but a certainty that our world will soon be full of self-driving cars. While Google’s self-driving vehicles have an impressive safety record in their limited testing, it’s just a matter of time until one is involved in a serious crash that injures someone in a vehicle, or a pedestrian.

So, in a way, it’s good news that Google is devoting some of its considerable intellectual energy to figuring out ways that we might lessen the seriousness of pedestrian injuries in the event of such collisions. Earlier this month, Google unveiled plans for a novel plan to coat the exterior of self-driving cars with a special adhesive that would cause any pedestrians the vehicles struck to adhere to the car rather than being thrown by the impact.

Whether it would be better to find oneself stuck to the car that struck you, rather than being pushed aside, is far from clear. But pedestrian safety in a world of self-driving cars is clearly an issue that needs to be dealt with.

Here at City Observatory, we’ve come up with our own concepts for, if you will, lessening the impact of autonomous cars on pedestrians. In the interest of safety and advancing the state of the art, we’re putting our ideas into the public domain, and not patenting any of them.

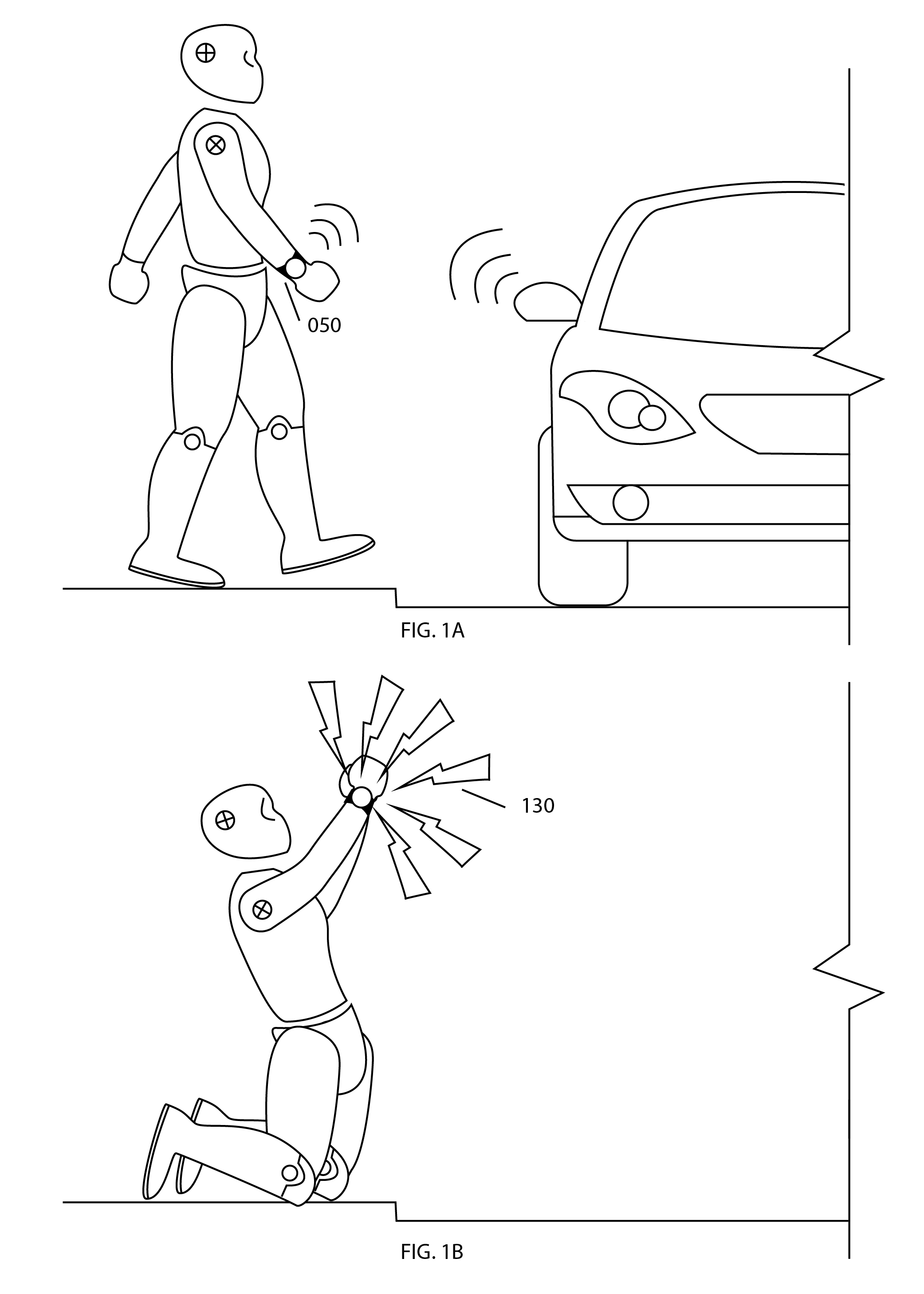

Pedestrian Shock Bracelets. Most pedestrians are already instrumented, thanks to cell phones, and a large fraction of pedestrians have fit-bits, apple watches and other wearable, Internet-connected devices. We propose adding a small electroshock device to these wearables, and making it accessible to the telematics in autonomous vehicles. In the event that the autonomous vehicle’s computer detected likelihood of a car-pedestrian collision, it could activate the electroshock device to alert the pedestrian to, say, not step off the curb into the path of an oncoming vehicle.

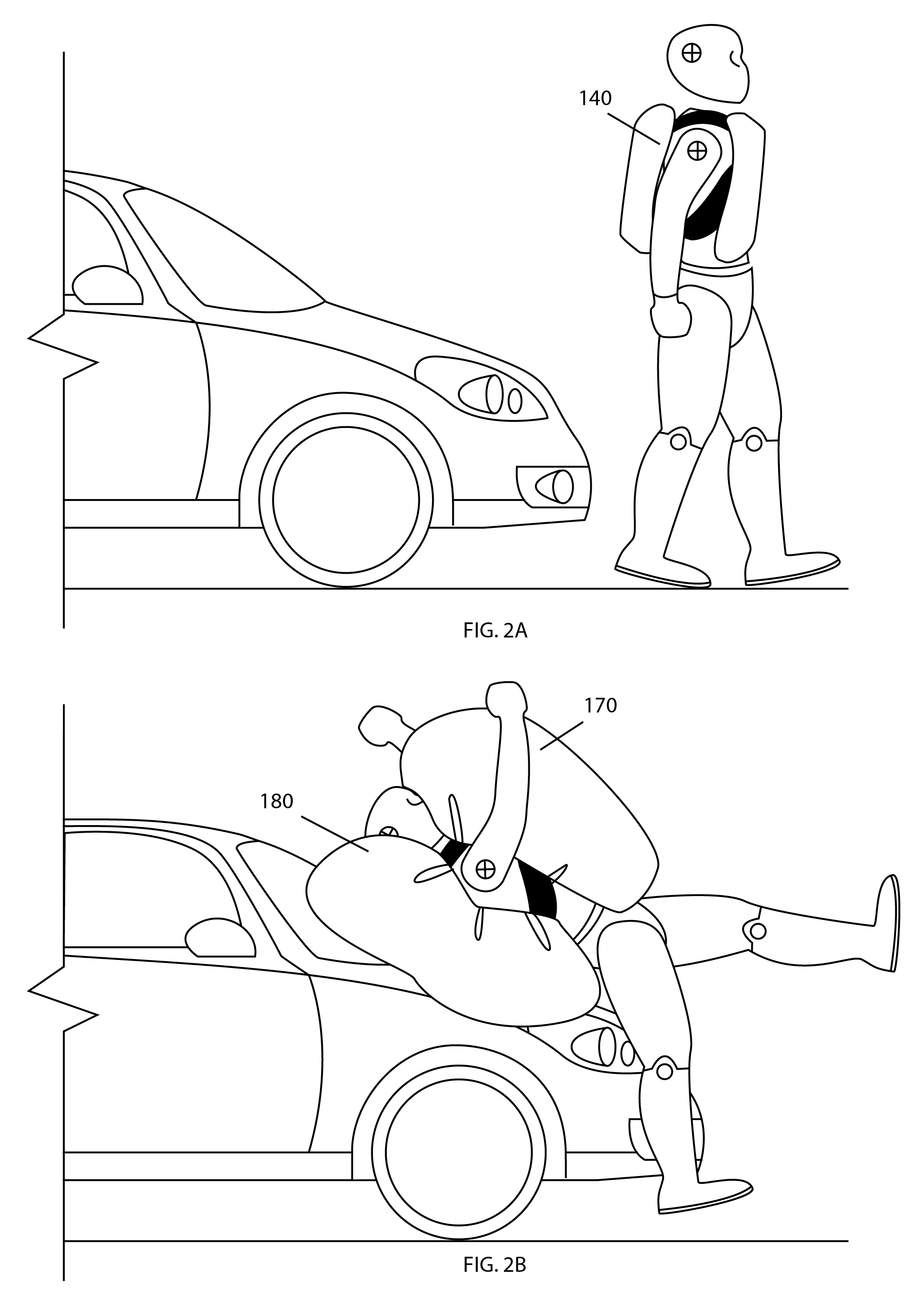

Personal airbags. Airbags are now a highly developed and well-understood technology. Most new cars have a suite of frontal impact, side curtain and auxiliary airbags to insulate vehicle passengers from collisions. The next frontier is to deploy this technology on people, with personal airbags. Personal airbags could have their own sensors, inflating automatically when the pedestrian was in imminent danger of being struck by a vehicle.

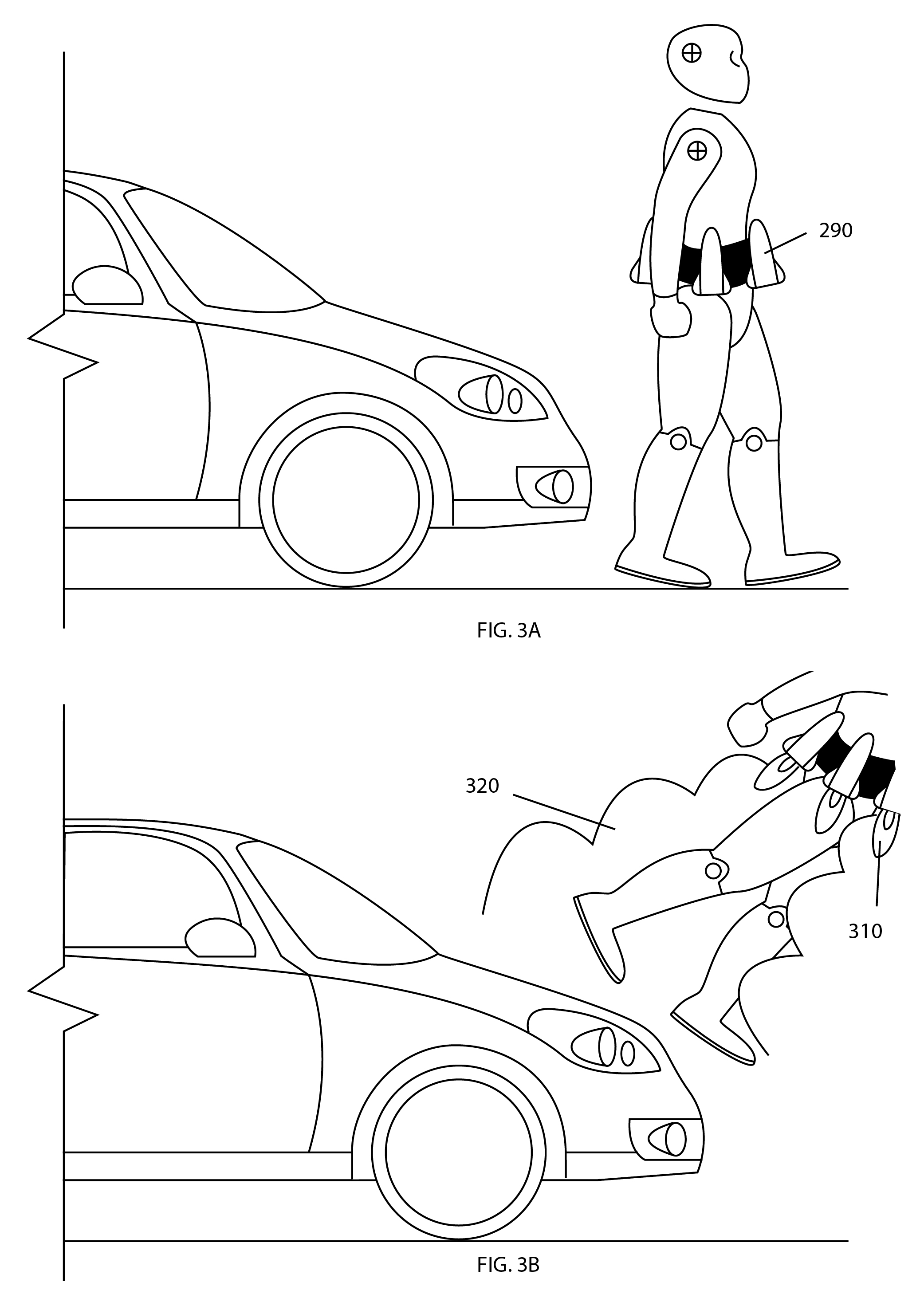

Rocket Packs. While a sufficiently strong adhesive might keep a struck pedestrian from flying through an intersection and being further injured, perhaps a better solution would be to entirely avoid the collision in the first place by lifting the pedestrian out of the way of the collision in the first place. If pedestrians were required to wear small but powerful rocket packs, again connected to self-driving cars via the Internet, in the event of an imminent collision, the rocket pack could fire and lift the pedestrian free of the oncoming vehicle.

We offer these ideas partly in jest, but mostly to underscore the deep biases we have in thinking about how to adapt our world for new technology.

It has long been the case with private vehicle travel that we’ve demoted walking to a second class form of transportation. The advent of cars led us to literally re-write the laws around the “right of way” in public streets, facilitating car traffic, and discouraging and in some cases criminalizing walking. We’ve widened roads, installed beg buttons, and banned “jaywalking,” to move cars faster, but in the process making the most common and human way of travel more difficult and burdensome, and make cities less functional.

Everywhere we’ve optimized the environment and systems for the functioning of vehicle traffic, we’ve made places less safe and less desirable for humans who are not encapsulated in vehicles. A similar danger exists with this kind of thinking when it comes to autonomous vehicles; a world that works well for them may not be a place that works well for people.

Consider this recent “Drivewave” proposal from MIT Labs and others to eliminate traffic signals and use computers to regulate the flow of traffic on surface streets. The goal is to allow vehicles to never stop at intersections, but instead travel in packs that create openings in traffic on cross streets that allowed crossing traffic to flow through without delay. Think of two files of a college marching band crossing through one another one a football field.

It’s thoroughly possible to construct a computer simulation of how cars might be regulated to enable this seamless, stop-free version of traffic flow. But this worldview gives little thought to pedestrians—the video illustrating drivewave doesn’t show any pedestrians, although the project description implies they might have access to a new form of beg button to part traffic flows to enable crossing the street. That might be technically feasible, but as CityLab’s Eric Jaffe pointed out, “it would be a huge mistake for cities to undo all the progress being made on human-scale street design just to accommodate a perfect algorithm of car movement.”

Not all of our problems can be solved with better technology. At some point, we need to make better choices and design better places, even if it means not remaking our environment and our communities to accommodate the more efficient functioning of technology.

Thanks to Matt Cortright for providing the diagrams for our proposed pedestrian protection devices.