“Affordable housing” can seem like a hopelessly vague term. First of all, affordable to whom? (Follow the link to a description of an “affordable” program targeting people making 40 percent more than the median income in San Francisco.) And even assuming we know who’s paying, what is a reasonable amount for them to pay?

But “affordable housing” also suffers from an ill-defined relationship to the market. Typically, the phrase “affordable housing” means “below market rate,” as in a home that receives some sort of subsidy, private or public, to be cheaper than what the owner could otherwise charge. (Of course, even this distinction—subsidized versus unsubsidized—is problematic, or just plain incorrect, given the massive subsidies to middle- and upper-income homeowners through mechanisms like the mortgage interest tax deduction.) But in most of the country, the vast majority of homes that are actually “affordable” to lower-income people are sold or rented at market rate. They just happen to have some characteristics—size, appearance, or location in a less-desired neighborhood—that make their market prices relatively low.

Homes that receive no special low-income subsidy, but are nevertheless relatively affordable, in Chicago’s Little Village neighborhood.

But very little private housing in the United States was originally built for low-income people. Instead, homes built for the middle or even upper classes gradually became cheaper as they aged, as people with high purchasing power moved into trendier, more modern homes in “better” neighborhoods. As higher income households move on, the now somewhat older homes or apartments they formerly occupied are sold or rented to people with more modest incomes.

This process is called “filtering.” While the evidence that filtering is a real phenomenon has been around for a long time—the core of nearly every American city contains neighborhoods with once-luxurious homes now occupied by people of modest incomes—the first study to provide a rigorous measure of how it happens was published only in 2013. In it, Stuart Rosenthal of Syracuse University uses nearly 40 years of data from the American Housing Survey to figure out the average pace of filtering across the country, and what makes housing filter more quickly in some places than others.

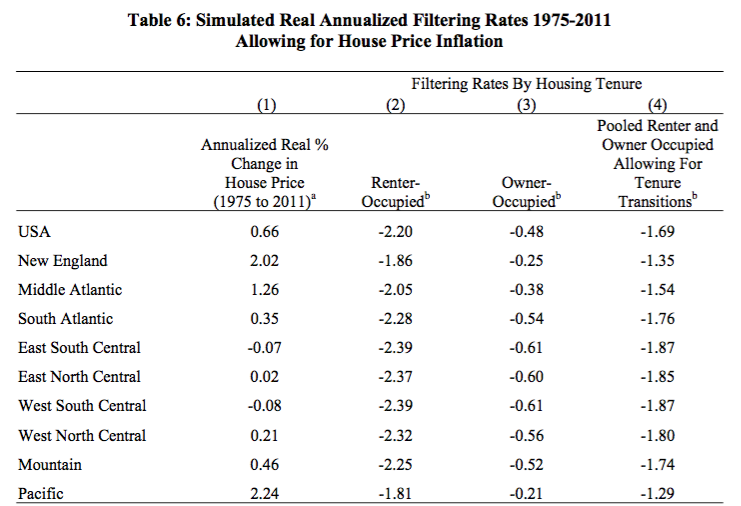

Rosenthal uses the AHS to compare the incomes of people living in the same units of housing over time. He estimates that nationwide, housing “filters” by roughly 1.9 percent a year—meaning that a 50-year-old home is typically occupied by someone whose income is about 60 percent lower than that home’s first occupant. (All of these numbers are adjusted for inflation.) You might think of this process as something like “reverse displacement.”

But that average nationwide figure obscures a lot of important variation. For one, owner-occupied homes filter much more slowly: just 0.5 percent per year, compared to as much as 2.5 percent for rentals. (Though homes that begin as owner-occupied are often converted to renter-occupied as they age.) Moreover, filtering doesn’t happen evenly over time: it’s much more dramatic over the first 40 years or so of a home’s life. That means the difference between a house that is brand new and one that’s 20 years old is much bigger than the difference between one that’s 60 years old and one that’s 80 years old. In fact, once a home hits the half-century mark, it’s as likely to “filter up” (become occupied by wealthier people) as filter down.

Perhaps the most important nuance, however, is that strong regional housing price inflation—that is, metropolitan areas where home values grow much more quickly than the cost of other goods—can make filtering happen much more slowly, or not at all. That helps explain why homes in New England and the West Coast filter about 35 percent more slowly than homes in the Midwest or South. In those coastal regions, severe restrictions on new housing construction since the 1970s have created a “shortage of cities,” driving up home prices and preventing the kind of filtering that has historically produced the lion’s share of affordable housing—and which still does in much of the rest of the country.

This makes a lot of intuitive sense: Filtering is driven largely by upper-income people who leave their aging homes for new ones. But if housing construction is restricted, there won’t be “enough” new homes, and some of those upper-income people will have to settle for older ones that might otherwise be occupied by people with less money. This is exactly the process that the apartments we wrote about in Marietta, Georgia went through. In the 1960s they were higher-end housing for middle-class singles and young couples; 50 years later, they were home to the city’s least prosperous citizens.

The lesson, then, is twofold. First, in normally-functioning housing markets, filtering really can produce a large amount of housing that’s affordable to people of modest incomes without special subsidies. One of the most common refrains in the housing affordability debate is that little to none of today’s newly-built housing directly serves low- or moderate-income households. And that’s true—but Rosenthal’s paper shows that that new housing is nevertheless crucial to making room for those households in older homes. While housing assistance is still necessary for people with very low incomes and to promote integration, the scale of the nation’s affordable housing challenge would be much, much greater without filtering.

Which leads to the second lesson. By putting severe limits on new housing, the wealthy metropolitan areas of the East and West Coasts have embarked on a several-decades-long experiment in what happens when housing filters down much more slowly than normal. The result has been a disaster: highly inflated prices for older homes that have left so little room for people of low and modest incomes that they’ve changed national migration patterns.

As a result, these regions have created a need for much broader and deeper housing subsidies than would be required if they had allowed for normal filtering. (Recall the link at the top of this post to a story about San Francisco giving significant housing assistance to people making over $100,000 a year.) In the short run, Rosenthal argues (and we agree) that his paper helps make the case for a dramatic expansion of housing assistance in these metropolitan areas.

But in the long run, he also shows that places like San Francisco and Boston must re-start the filtering process. Many of these regions, by refusing to make that room, have clearly already reached the point where no realistic amount of low-income subsidies will create a sufficient amount of affordability—and if legal restrictions on new construction continue to exacerbate their housing shortages, that gap will only widen further.