Ten things legislators, reporters and citizens should know about the special session

In the next week, the Oregon Legislature will meet in special session to take up transportation finance. A draft bill, LC 2, is being considered. In theory, ODOT’s share of a six cent gas tax increase and parallel fee increases is a “band-aid” to just cover maintenance and operation shortfalls.

But ODOT can—and has repeatedly—diverted any available money to start huge mega-projects and then pay their ensuing cost overruns. That’s the real cause of the agency’s financial woes, and LC 2 does nothing to prevent that from happening in the future.

Here are ten facts everyone should know about this transportation package:

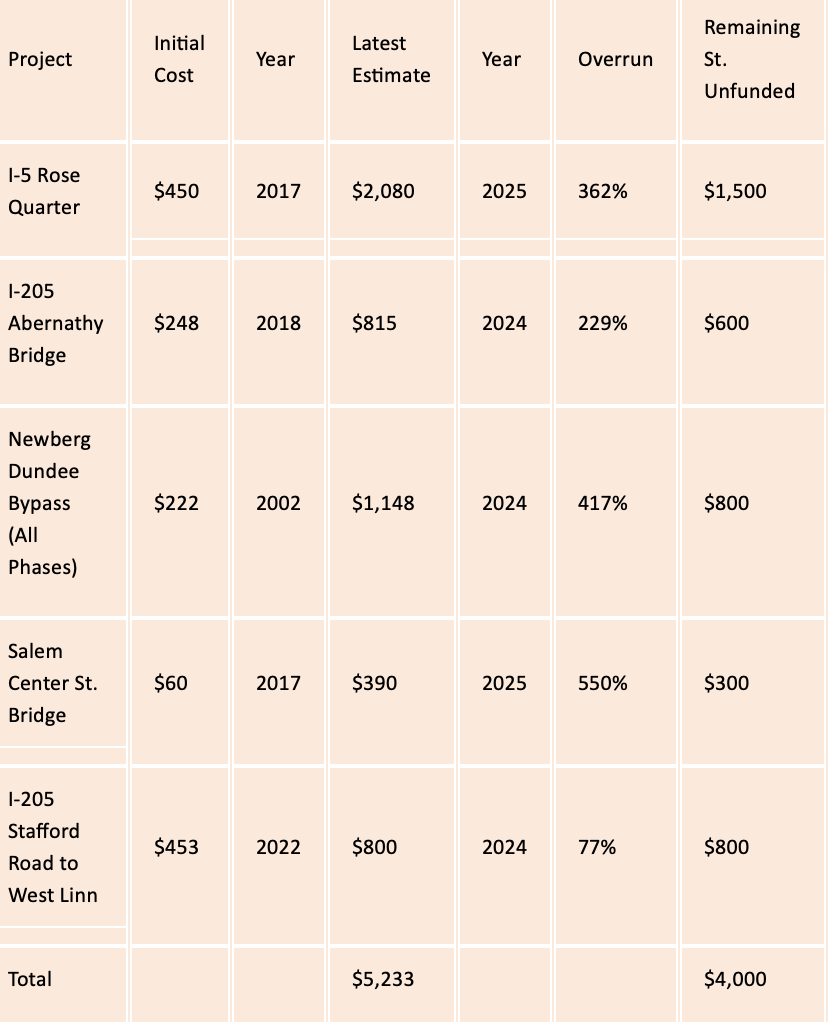

- Cost Overruns. ODOT’s financial problems are largely due to cost overruns on mega-projects. ODOT projects are exploding in costs: The Abernethy Bridge has tripled from $250 million to 815 million, and the Rose Quarter has quadrupled from $450 million to $2.1 billion. And more megaproject cost overruns threaten future budget stability.

This is alarming because essentially none of ODOT’s explanations of its budget woes make any reference to cost overruns. If you don’t acknowledge that you have a problem, you can’t possibly fix it.

- Requiring Maintenance. There no guarantee LC 2 will fix ODOT’s obsession with megaprojects. Nothing in LC 2 restricts new ODOT funding to paying for maintenance and operations. The Oregonian editors wrote on August 24, 2025:

And even as state officials paint a dire picture of crumbling roads, unplowed highways and other maintenance nightmares if new taxes aren’t approved, they have yet to insert any language that requires the new revenue to go to those crumbling roads, unplowed highways and other maintenance nightmares.

Instead, elected officials and ODOT could choose to use those dollars to support ongoing highway megaprojects whose costs have already quadrupled their original estimates, exposing ODOT’s profound “accountability” gap.

- Borrowing against future revenue. Debt is a powerful tool for diverting revenue from basic priorities to expensive frills. ODOT could borrow against future new LC 2 revenue to fund megaproject cost overruns.

ODOT has repeatedly used its short-term borrowing authority—which doesn’t require legislative authorization—to borrow against future gas tax revenues to pay for current expenses. In the past 2 years, ODOT has borrowed $271 million using this government equivalent of a payday loan, and used it, in part, to cover cost overruns on the Abernethy Bridge project, .

- No accountability. There are no new accountability measures in LC 2, and they have already been proven ineffective.

LC 2 provides for a legislative oversight committee and audits, which have been tried before and failed. Nothing in LC 2 really provides for any accountability.

Tried and failed accountability measures

| Proposed “Accountability” Measures | Previously Implemented Oregon Measures |

|---|---|

| Create a “major projects office” to centralize management of large projects | 2019: ODOT created the “Office of Urban Mobility and Megaproject Delivery” |

| Create a “major projects dashboard” | 2022: ODOT launched “Transportation Project Tracker” (updated daily) |

| Establish joint executive/legislative/stakeholder “major projects committee” to oversee large projects | 2017: Legislature created “Task Force on Transportation Mega Projects” and “Continuous Improvement Advisory Committee” |

| Employ “RACI” management tool (responsibility, accountability, consultation, information) for decision-making processes | 2017: McKinsey recommended RACI to ODOT; agency already maintains RACI checklists for contracting |

One accountability measure is having the Governor appoint the ODOT director; ironically this exactly reverses what was billed as an accountability measure in HB 2017: giving appointing authority to the Oregon Transportation Commission.

Even when the Legislature required some accountability in the form of “sideboards” for the Interstate Bridge Project, ODOT simply got them repealed in a late in the session measure that got essentially no public debate.

- Phony claims to prioritize maintenance. ODOT has always claimed it prioritizes maintenance, when in fact it doesn’t. Last time the Legislature passed a major transportation package, ODOT claimed it would prioritize operations and maintenance, before expanding the system–it didn’t.

Here’s the agency’s current deputy director, Travis Brouwer, speaking to OPB, in April, 2017 as the Legislature was considering a giant road finance bill.:

Of course, patching potholes are far from the only thing ODOT has to spend money on. So how does the agency decide what to prioritize? According to ODOT assistant director Travis Brouwer, basic maintenance and preservation are a top priority.

“Oregonians have invested billions of dollars in the transportation system over generations and we need to keep that system in good working order,” he said. “Generally, we prioritize the basic fixing the system above the expansion of that system.”

Back in 2017, the Oregon Department of Transportation put out a two-page “Fact Sheet” on the new transportation legislation. It’s first paragraph stressed that most of ODOT’s money would be for maintaining the existing system:

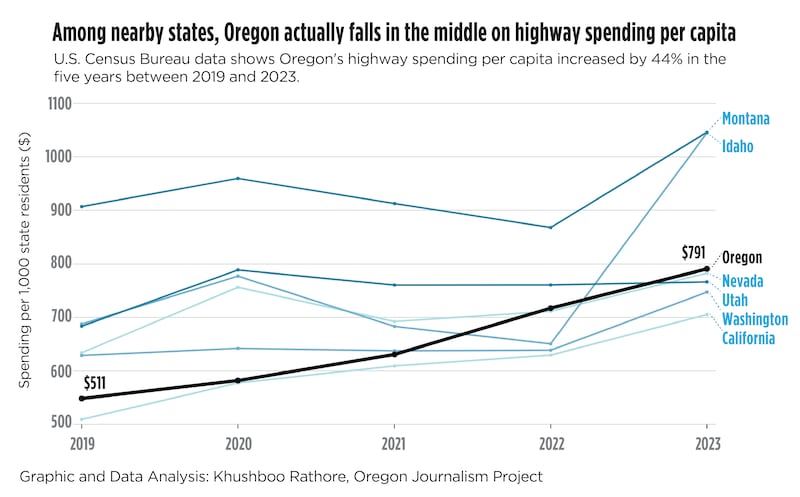

- Misleading spending comparisons. ODOT fabricated a misleading comparison of state transportation taxes which has been used to claim Oregon spends less on transportation than other states, which is untrue, according to Willamette Week:

Oregon falls roughly in the middle of the other six states cited by ODOT: California, Washington, Nevada, Utah, Idaho and Montana (see graph below).

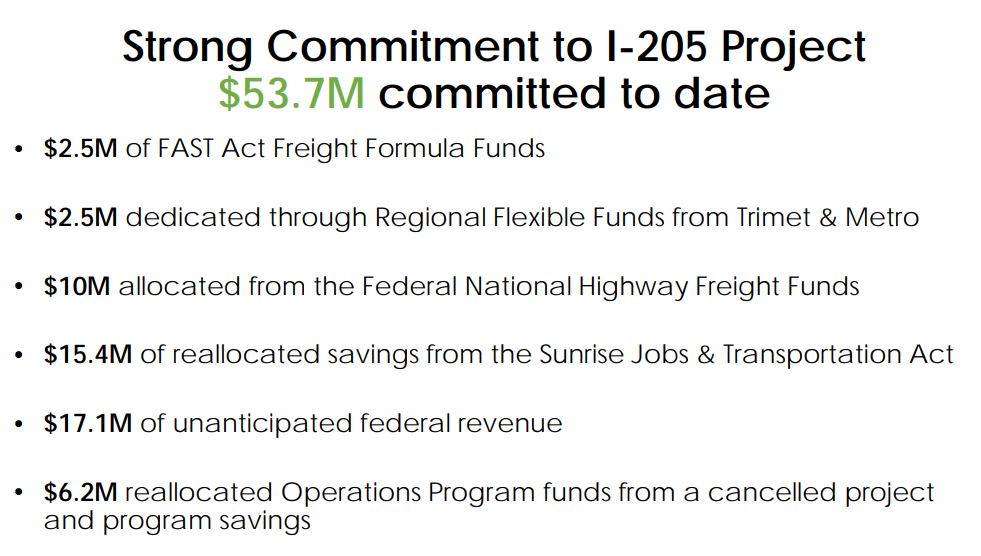

- Diverting preservation and operations money to mega-projects. Contrary to claims that its discretion is limited, ODOT has repeated diverted both operations and preservation funds to pay for the Abernethy Bridge—a project for which the legislature has provided no dedicated funding, even though its costs has grown to $815 million. In 2018, ODOT started the Abernethy Bridge by diverting $6.2 million from operations programs.

In December 2024, The Oregon Transportation Commission approved taking $100 million set aside for bridge preservation to pay for a portion of the cost overruns on the I-205 project.

- Motor fuel tax revenue hasn’t declined. ODOT’s revenue has not declined: Motor fuel tax revenue is up nearly $100 million over the past five years.

Between Fiscal Year 2020 and Fiscal Year 2024, motor fuel taxes on diesel and gasoline sales in Oregon increased by $97 million. That pales in comparison to the increase in mega-project costs, which have gone up by about $4.7 billion. Revenue isn’t actually declining as ODOT claims, and fuel efficiency and electric vehicles are not to blame for ODOT’s fiscal problems.

- Hiding a new IBR cost estimate. ODOT is hiding a new Interstate Bridge cost estimate which will add billions to ODOT’s unfunded costs

For the past 20 months, ODOT has been doing its best to conceal the rising cost of the Interstate Bridge Replacement Project. In January 2024, project leaders admitted the price was going to rise from the estimated $7.5 billion maximum. Now they say a new estimate won’t be available until late this year or early next. It’s likely to push the project’s cost into the $9-10 billion range, with Oregon’s share being an additional $1-2 billion. That means we’ll face another crisis, and added pressure to divert money from maintenance before the ink is dry on LC 2.

- Rose Quarter $1.5 billion deficit. The Rose Quarter project faces a $1.5 billion deficit, yet ODOT is proceeding with construction

ODOT lost more than $400 million in federal grant funding, and the project’s cost has ballooned to more than $2.1 billion, but ODOT contintues to move ahead, even though the Daily Journal of Commerce reports the state’s own analysis shows it will be “exceedingly difficult or impossible to complete the project.

“While an initial $60 million contract for paving and stormwater work that is part of phase 1 has advanced, constructing the remainder of phase 1 and phase 2 will be exceedingly difficult, if not impossible, without federal funding,” the Financial Office [DAS] stated.