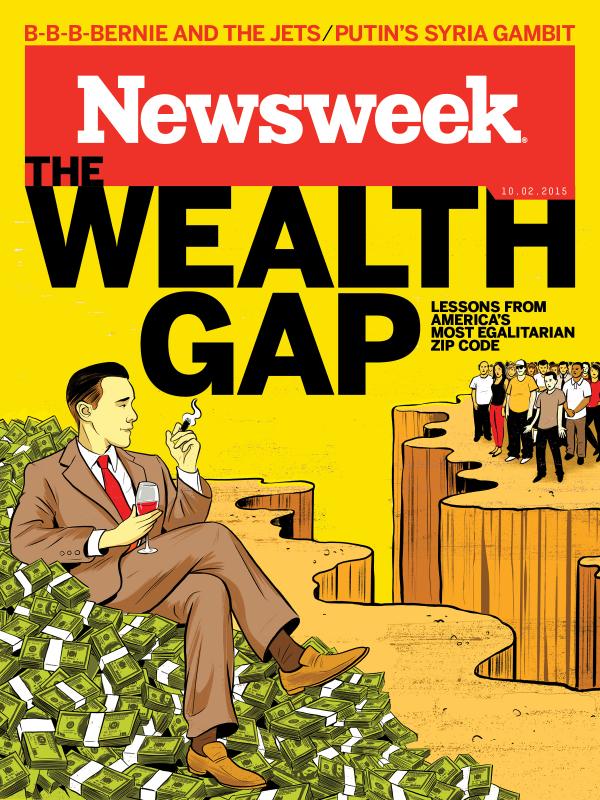

Two recent press features have suggested that one Utah city has worked out the recipe for equitable development. The cover story from Newsweek’s October 2, issue offers “Lessons from America’s most egalitarian zip code.” It proposes that Ogden, Utah is a model for how the US can address income inequality.

The article is at least the second in this vein. Writing in the Los Angeles Times in July, writer Don Lee said that quiet Ogden offers a surprising glimpse of income equality.

The premise of both of these stories is that the Ogden-Clearwater metropolitan statistical area has the lowest reported Gini coefficient (.3949) of any U.S. metropolitan area, an indication that income inequality is less there than in any other place.

The fact that one metropolitan area should have a measured rate of inequality that is lower than other metropolitan areas is hardly a surprise: somewhere, obviously, has to rank first, and somewhere else has to rank last. From a policy perspective, however, the question has to be: Is there anything we can learn from Ogden that we can apply to other metropolitan areas, or the nation as a whole?

Ogden has several unique characteristics. First, it’s very much in the economic orbit of the considerably larger Salt Lake City metropolitan area. While it is now classified as a separate metropolitan area, until 2000 Ogden and Salt Lake City were combined for federal statistical purposes. In some respects, Ogden resembles a large somewhat distant suburb of Salt Lake. Like many metropolitan areas, very high income and very low income households are somewhat more likely to be found in the urban center. Just as many of the suburbs of metropolitan areas have measurably less inequality than large urban cities, it shouldn’t be any surprise that Ogden has lower measured inequality than Salt Lake City.

As we pointed out in our post, high marks for equality may actually be a symptom of exclusiveness rather than equality: cities that exclude poor people frequently have higher measured equality than do more inclusive cities.

It’s also worth considering the structure of the Ogden economy. Two of the largest employers are arms of the federal government: Hill Air Force Base and the Internal Revenue Service. While neither pays particularly high wages, federal jobs are disproportionately large source of jobs and income in Ogden. According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, federal payrolls account for more than 15 percent of all non-farm income in Ogden: more than $2 billion annually in a local economy of about $13.7 billion. And at more than 12 percent of the local economy, the share of Ogden’s metro economy made up of federal civilian payrolls is the third-highest in the country among large and mid-sized metropolitan areas. Federal paychecks are a bigger share of the local economy only in Huntsville, Alabama, and metropolitan Washington, D.C. In the typical large metropolitan area, federal civilian payrolls make up about 2.2 percent of the local economy; in Ogden, they are more than five times larger.

One thing is clear about the Utah experience: Cities in Utah (and many other Mountain West states) have higher rates of measured intergenerational economic mobility than the U.S. as a whole. Relying on statistics from the landmark Equality of Opportunity study conducted by Raj Chetty and his colleagues, both articles report than kids growing up in poor households have measurably better chances of moving up in the income distribution as adults than the typical American.

The Newsweek article attributes the city’s low rates of inequality to its economic and community development efforts. Apparently the city has revived its downtown and added to employment in the past decade or so. But there’s little evidence that higher measured equality in Ogden is the product of any recent policies or programs. The Chetty study measured the intergenerational mobility of kids who grew up in Ogden in the 1980s and ‘90s—at a time when Newsweek says the economy and community were struggling. And even in 1999, Ogden—then combined with Salt Lake City for federal statistical purposes—had one of the nation’s lowest levels of measured inequality. And as we’ve noted, the same pattern holds for many other communities in the Inter-Mountain West.

The statistics in the Chetty study show that the strong correlates of high intergenerational mobility across all communities are intact families, strong schools, limited sprawl, and low levels of racial and ethnic and income segregation. These factors tend to be more deep-seated and slow changing than economic development programs.

So what are the real lessons Ogden offers for those looking to reverse the growing tide of inequality in the US?

First, it really helps to have a strong source of good, or at least middle-wage, jobs. While those have been increasingly hard to find in the private sector, if you’re lucky enough to have a substantial government employment presence—like a big military base or extensive administrative offices—you’ll probably have a bit more income equality. Whether that’s a recipe for other communities or the nation isn’t clear: quintupling the number of federal jobs in every metropolitan area doesn’t seem to be on anyone’s political agenda. Being one of the fortunate few cities with a large concentration of government employment isn’t a scaleable solution to inequality.

Second, while some smaller metros on the periphery of a big city do well on the inequality statistics, many of the problems of inequality end up being outsourced to cities. Suburbs, especially exclusionary ones, tend to ban the kinds of affordable housing construction that enable poor people to live in a community. Cities offer a bigger base of job opportunities, more affordable transportation (workable transit systems) and often have better social support networks. Cities also attract high income households. Big city centers have more inequality, but it’s because they facilitate diversity and inclusion—not because they generate inequities.

While it may show up differently in different locales, the roots of the nation’s inequality problem are national and not merely the sum of local inequalities. The diminished value of the minimum wage, the falling clout of unions to raise worker wages, the growth of global competition, a tax code that favors the accumulation of wealth and the rise of superstar returns in a range of industries have all caused inequality to increase nationally. These challenges are largely beyond the power of cities to address.

Ironically, as we’ve pointed out at City Observatory, those places with a low measured level of equality may be the one’s that are the most diverse and inclusive, providing both attractive places for talented higher income workers to live and invest, and also providing access to housing and job opportunities for those at the bottom of the income scale.

So the story of Ogden is reminiscent of H. I. McDonough’s dream at the end of “Raising Arizona”:

But still I hadn’t dreamt nothin’ about me ‘n Ed, until the end. And this was cloudier, ’cause it was years, years away. But I saw an old couple bein’ visited by their children, and all their grandchildren too. The old couple wasn’t screwed up, and neither were their kids or their grandkids… And I don’t know. You tell me. This whole dream, was it wishful thinkin’? Was I just fleeing reality like I know I’m liable to do? But me and Ed, we can be good, too. And it seemed real. It seemed like us, and it seemed like, well, our home. If not Arizona, then a land not too far away, where all parents are strong and wise and capable, and all children are happy and beloved. I don’t know. Maybe it was Utah.