New York City is getting all the attention–much deserved–for the breath-taking success of congestion pricing.

Speeds are up, congestion is down, there are fewer crashes, less noise, more people on the streets and better business.

But congestion pricing also works in much smaller metro areas, and doesn’t depend on big investments in transit to work wonders

Louisville, Kentucky’s pricing of the I-65 bridges has reduced traffic by half on I-65, and lowered total crossings of the Ohio River by 15 percent.

Residents of the suburban county North of Louisville now drive about 18 percent fewer miles per day than before pricing was implemented.

Traffic congestion, and bloated highway construction costs, are result of our failure to manage our roads with pricing

There’s a persistent myth in transportation policy that you can’t do pricing until you provide copious and comprehensive improved transit alternatives. That’s bunk. Pricing makes road systems more efficient by giving people incentives to drive less, particularly at peak hours.

Even if some people have no option but to use a priced roadway, many, if not most users have abundant options: they can take alternate routes, travel at different times, change destinations, combine trips, as well as take transit, bike and walk. They can even forego some trips entirely. Transportation policy is founded on a “lump of travel” fallacy: that whatever trips we observe people making are an irreducible minimum: people must travel between a set of origins and a set of destinations, and will do so regardless of the transportation system, or any road pricing.

That’s nonsense, as repeated “carmageddon” experiences show. When roadway capacity is removed–for example by a bridge failure, or fire, or natural disaster, or construction project–traffic doesn’t mindless pile up lemming-like. Instead, much traffic actually evaporates: fewer trips are taken when roadway capacity is reduced. Travel demand, especially car travel in urban environments, is like a gas: it expands to fill available capacity, but if constricted it can be compressed.

Pricing eliminates congestion in Louisville

The recent experience of Louisville Kentucky shows that, just as in New York, pricing leads to significant reductions in traffic and traffic congestion. While it costs you $9 to drive into Manhattan South of 59th Street, it costs you $2.61 to drive across the Ohio River on I-65 into downtown Louisville from Southern Indiana (and vice-versa). And guess what: Just like in New York, pricing dramatically reduced traffic.

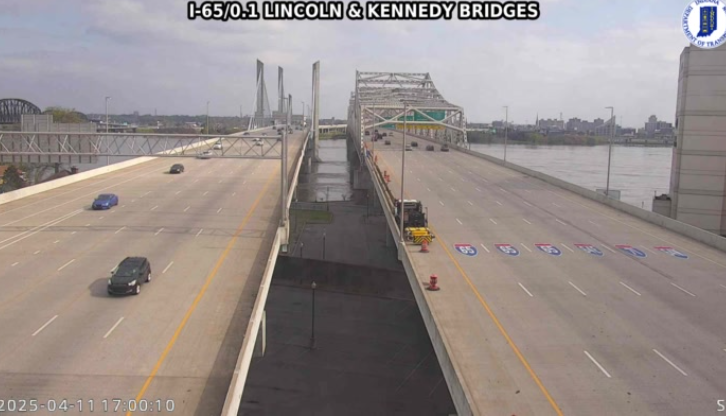

Friday, 5 PM Traffic on I-65 Lincoln and Kennedy Bridges (April 11, 2025).

These pictures were taken by a traffic camera pointed at the I-65 bridges across the Ohio River at Louisville, Kentucky on Friday, April 11, 2025 at rush hour (5:00 pm). Traffic engineers have a term for this amount of traffic: They call it “Level of Service A”—meaning that there’s so little traffic on a roadway that drivers can go pretty much as fast as they want. Highway engineers grade traffic on a scale from LOS A (free-flowing almost empty) to LOS F (bumper-to-bumper, stop-and-go). Most of the time, they’re happy to have roads manage LOS “D”.

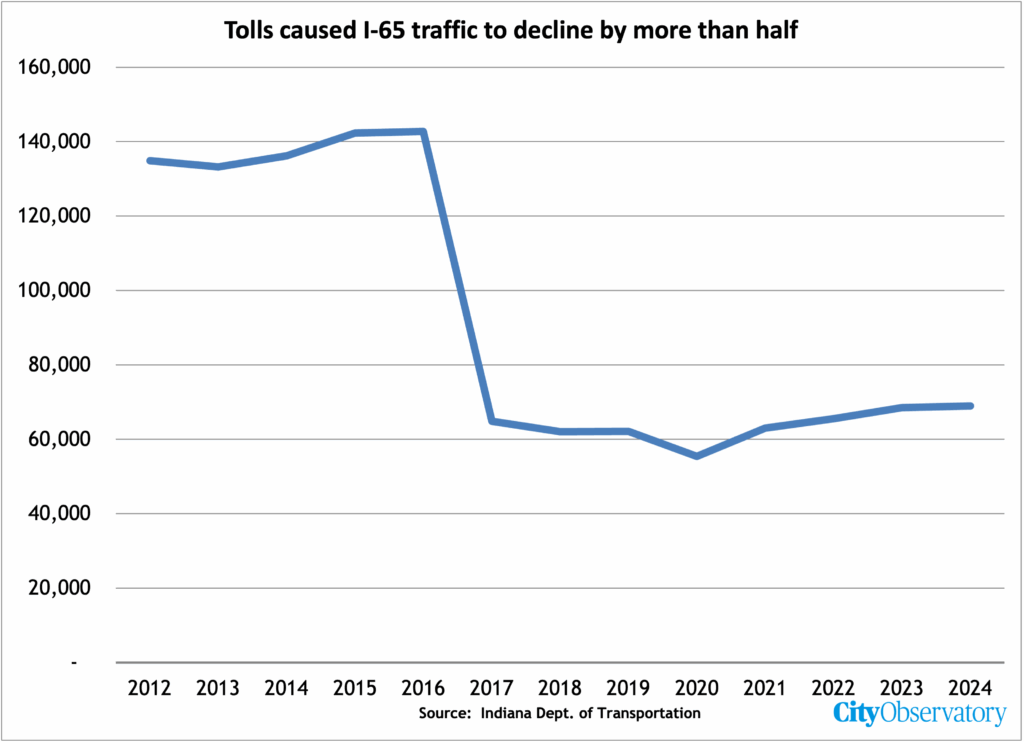

A decade ago, the then six-lane I-65 was much more crowded. Kentucky and Indiana spent about a billion dollars to double the size of I-65 across the Ohio, and to pay for part of it, they started charging a modest toll. After the tolls went into effect in 2017, traffic on I-65 fell by half. Here’s the average daily traffic count on I-65, according to data tabulated by the Indiana Department of Transportation. In the years just prior to the tolling, traffic was in the 135,000 to 140,000 vehicles per day level. But as soon as tolling went into effect, traffic dropped to 60,000 vehicles per day (with a very slight downward blip due to Covid-19 in 2020).

Tolling has reduced car travel across the Ohio River

Obviously, tolling the i-65 bridges ought to decrease traffic on I-65, but there’s evidence that total traffic across the Ohio River is lower now, and much lower than predicted for this project. Recall the that rationale for widening I-65 and also building a new I-165 crossing on the eastern edge of the metro was to relieve congestion and accommodate a huge predicted increase in traffic across the Ohio River. But with tolling, not only has traffic across the river failed to come close to projections, but has actually declined from pre-construction levels–even there’s a new crossing and many more lanes across the river. The following table compares traffic volumes on the 3 bridges across the river in 2014 with the 2024 projected and actual levels of traffic across the five bridgs in 2024. (The projections are from the Investment Grade Traffic and Revenue study prepared by CDM Smith)

| Louisville Area Ohio River Crossings | ||

| Total | Change from 2014 | |

| 2014 Actual | 239,000 | – |

| 2024 Predicted | 292,000 | +53,000 |

| 2024 Actual | 205,000 | -34,000 |

The traffic study predicted that traffic would rise more than 20 percent over the decade, increasing by more than 50,000 river crossings per day over 2014 levels. Instead, pretty much the opposite happened: total traffic across the river fell my more than 15 percent, by about 34,000 trips per day.

Tolling also appears to have reduced driving in the region

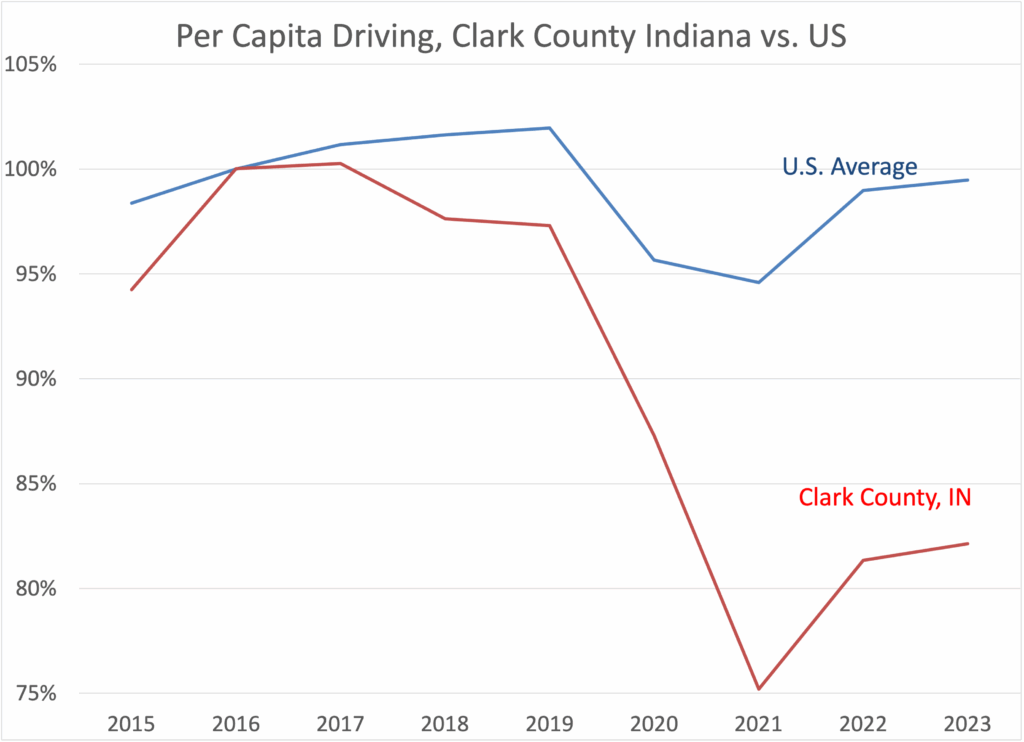

And it isn’t just river crossings that have declined. Data from Clark County, Indiana, the suburban county just North of Louisville on I-65, shows that per capita daily auto travel has declined significantly since the bridge was tolled. (Clark County is the second most populous county in the region, and has seen steady population growth before and after bridge construction). Daily vehicle miles traveled (VMT) per person in Clark County declined from 38.8 in 2016, just before the bridge tolls were implemented, to 31.9 in 2023 a decline of 18 percent. At the same time VMT per person in the US fluctuated, and declined by 0.5 percent. The following chart shows the trend in VMT per capita for the period 2015 through 2023 with (2016 = 1.0).

On its face, this evidence suggests that tolling the I-65 bridges reduced significantly the amount of driving in Clark County. A pernicious myth of pricing is that it will somehow trigger vastly more driving as people go out of their way to avoid tolls. But strikingly the evidence from Louisville shows that tolling the I-65 bridges actually reduced the driving. Traffic across the Ohio River has actually gone down since the tolls were imposed (even though there is now a mix of tolled and non-tolled bridges (the I-64 bridges to the west of downtown are un-tolled, as is the older and much narrower US 31 bridge near downtown; the new I-165 bypass bridge to the east is tolled just like I-65).

Managing demand, at last

These observations are consistent with the principle of induced travel: People take trips more trips and longer trips when roads are free than when they have to pay for those trips.

There are many who dismiss the applicability of congestion pricing to cities other that New York because they don’t have either the subway system or comprehensive bus service to handle trips displaced by pricing. That misses the point that even in New York, most of the gain comes from reducing trip taking–not shifting trips to transit. Even in a typical, relatively automobile dependent U.S. metropolitan area, road pricing leads to less travel and less congestion.

We’re at a point where attempting to fix urban congestion by expanding highways is prohibitively costly (as well as futile). Adding a lane or two to an urban freeway in Portland costs only the order of a billion dollars a mile. That expenditure could be avoided, and traffic congestion solved, if states would implement congestion pricing.

It’s great when the proceeds of congestion pricing are invested to make other transportation alternatives more widely available, but as one pundit noted, it would still be a net positive for society even if you lighted the proceeds on fire. Charging a price for the use of a scarce resource improves efficiency, and using the proceeds to promote alternatives is both better and fairer than an inefficient system that clogs roads and slows everyone by pretending to provide service for “free.”

You can make it there, you can make it anywhere

Usually, as we know, simply widening highways, to as many as 23 lanes, as is the case with Houston’s Katy Freeway, simply generates more traffic and even longer delays and travel times. And, with no sense of irony, highway boosters even tout the Katy Freeway as a “success story,” despite the fact it made traffic congestion worse. In contrast, Louisville’s I-65 is an extraordinarily rare case where traffic congestion went away after a state highway department did something.

You’d think that the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet and the Indiana Department of Transportation would be getting a special award, and holding seminars at AASHTO to explain how to eliminate traffic congestion. The fact that they aren’t tells you all you need to know about the real priorities of state highway departments–they really only care about building things, not about whether congestion goes away or not.

The default pundit view is that New York City is the only place in the US where pricing makes sense because of the availability of buses and subways. The Louisville traffic experience shows us that there’s a surefire fix for traffic congestion that works, not just in New York City, but even a mid-sized metro area: road pricing. Even a very modest toll (one that asks road users to pay only a third or so, at most of the costs of the roads they’re using) will cause traffic congestion to disappear.

If state DOTs really cared about congestion, they’d be implementing congestion pricing. A small toll, probably less than a dollar per crossing, would have been sufficient to get regular free-flow conditions on the I-65 bridge—without having to spend a billion dollars. But the truth is, state DOTs don’t care about congestion, except as a talking point to get money to build giant projects. The next time you hear someone lamenting traffic congestion, ask them why they aren’t trying the one method that’s been shown to work.