The Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) blames its financial crisis on declining revenue from cleaner, more efficient cars.

The reality is that the agency suffers from chronic overspending on highway megaprojects.

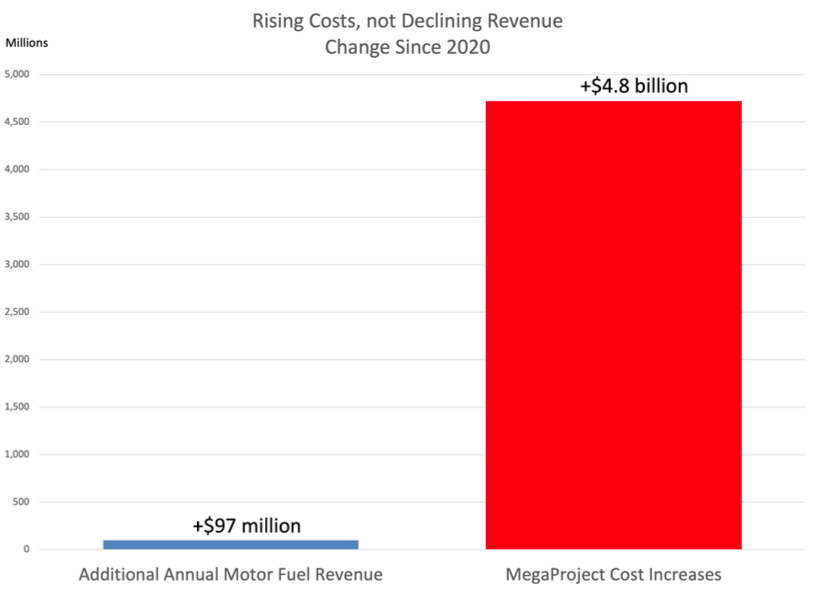

Motor fuel revenue is actually up $100 million per year compared to 2020, but in the past five years, cost overruns on just three Portland area highway expansion projects in amount to nearly $5 billion.

ODOT has a spending problem, not a revenue problem.

ODOT’s poor management is to blame for these overruns, and they promise to become worse in the years ahead.

Joe Cortright’s testimony to the Oregon Transportation Commission

March 13, 2025

For the record. Joe Cortright, I’m an economist with City Observatory. I’d like to address two issues on the agenda today. They have to do with finance and climate.

ODOT claims to be facing a fiscal crisis, and it blames electric vehicles and more efficient cars. It says:

“. . . with increased fuel efficiency and more EVs, Oregon sees lower tax revenue and less money available to maintain the transportation system.”

In fact, that’s untrue. Annual motor vehicle fuel tax revenue, the revenue source most closely tied to fuel consumption, is up by $100 million over the last five years, and going forward, the latest revised forecast has increased the amount of money you expect from motor fuel taxes by $60 million from now through 2033

The real problem isn’t revenue. It’s mega project cost overruns:

- The Interstate Bridge Replacement (IBR) project has gone from $4.8 billion up to $7.5 half billion, and will go higher still

- The I-5 Rose Quarter freeway widening was approved at $450 million, and is now 1.9 billion.

- The I-205 Abernathy bridge was given a go ahead at $250 million; it’s now $815 million, and will go higher.

To put these cost overruns in perspective, costs on just these three projects have risen by $4.8 billion in the last five years, which is vastly greater than any change in motor fuel tax revenue–which has been up.

ODOT is a spending problem, not a revenue problem. And that’s not all we know. The Hood River Bridge has gone from $500 million to $1 billion dollars; the Salem Center Street bridge tripled to $200 million. There are a lot of reasons for these cost overruns, but there’s a common element. Four of them are bridges and drilling shafts for these bridges is vastly more difficult and expensive than ODOT has estimated, and they have overlooked key geo-technical issues.

And it’s not that they’re not aware. IBR’s risk analysis, published two years ago, showed that they knew there were problems with drilling shafts. They called it ” a contractor’s pot of gold,” meaning that when you ran into obstacles, there’d be change orders and contractors would make lots of money.

It’s a management axiom that you get the behavior that you reward. And faced with chronic overruns, this body, the Transportation Commission, has time and again, frowned, shrugged, and then simply given more money to the same people to do more of the same. You are rewarding people for low-balling early cost estimates, minimizing and ignoring risks, and then they stick you with the bill later on.

As a result, we can expect more of the same in the future. In fact, all three of the mega projects I mentioned earlier are all pending new and higher cost estimates. And the Interstate Bridge Project which knew it needed to increase its estimate in January of 2024 has delayed releasing a new cost of estimate until June of this year, i. e. after the legislature adjourns. So you have cost overruns, because that’s what you’re managing for. That’s the set of incentives you’ve given to your employees and to contractors. That, not declining revenue, is the source of your financial problems.