What City Observatory did this week

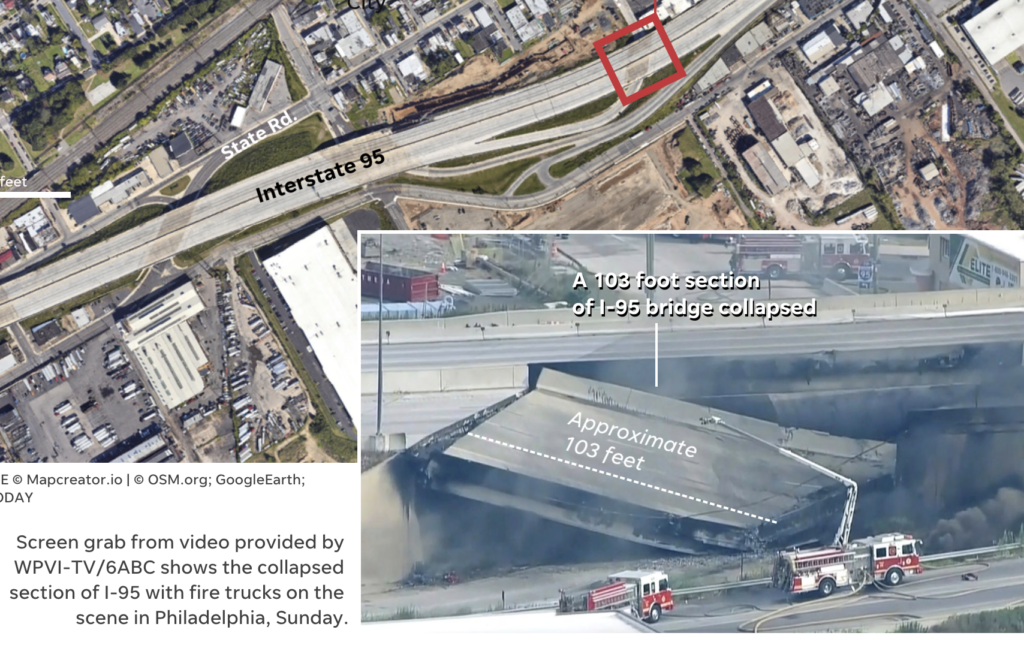

Carmageddon does a no-show in Philly. A tanker truck caught fire and the ensuing blaze caused a section of I-95 in Philadelphia to collapse. This key roadway may be out of commission for months, and predictably, this led to predictions of “commuter chaos.” But on Monday morning, traffic in Philadelphia was surprisingly . . . normal.

It’s yet another instance of traffic evaporation–when roadway capacity is suddenly reduced (by a disaster or construction project), travelers quickly adapt to the newly constrained roadway system. This evaporation is the mirror image of “induced demand”–the tendency of newly widened roadways to fill up and become just as traffic clogged as before. The lesson of these false carmageddons is that travel is much more dynamic and flexible than we imagine.

Must Read

Block that metaphor: Stop saying micromobility. In an incisive essay for Streetsblog, Sarah Risser questions our use of the term “micromobility” to describe bikes, e-bikes, scooters and other similarly sized modes of transport. In this case, the use of the diminutive effectively diminishes the seriousness of these modes of transport, and reinforces the notion that that there are “regular” or “normal” modes of transport (cars, trucks, SUVs), and that smaller, safer greener ways of getting around are just toys, or marginal and substandard modes.

This kind of subtle bias pervades much transportation policy debate (calling all crashes “accidents,” and the term “jay-walking”). As Risser says:

SUVs, pick-up trucks, and passenger cars should not be the benchmark by which we judge the size of other forms of transit, and the term ‘micromobility’ encourages us to believe that they are. Instead, we should intentionally drop the preface “micro” in micromobility and start referring to bikes, scooters, and the human body simply as “mobility,” And we should also add an appropriately descriptive prefixes to ever-larger cars, SUVs and pick-up trucks: Maybe we could call them “oversized-mobility;” “space-hogging-mobility”; or better yet, “deadly-mobility.”

The words we use matter: We shouldn’t inadvertently embrace and reinforce automobile dominance by using a term that marginalizes sustainable, human-scaled transport.

Will Minnesota live up to the promises of its new transport legislation? There’s some good news that’s come out of Minnesota, where the legislature adopted language injecting some sound climate protection policies into the state’s transportation investment laws. Writing at StreetsMN, Alex Burns takes a closer look at the fine print, and points out, that while there’s progress, there’s a lot more work to do here. Although the law requires an emissions analysis for new highway expansion projects, the bill essentially grandfathers everything that’s already in an adopted highway plan, which is bad enough, and could get worse if highway engineers amend those plans before the new laws take effect in 2025. Burns writes:

. . . the bill did add some important protections against highway expansion but they do not go far enough [it] requires MnDOT to assess the impacts of a project on state climate and vehicle miles traveled (VMT) goals and perform mitigation measures only if the project adds travel lanes. A project that reconstructs a freeway with the same number of lanes is exempt, even though it will likely mean 60-plus more years of greenhouse gas emissions (not to mention air pollution, noise and human carnage) over that project’s lifespan.

More to the point, the legislation still provides the bulk of state funding for roads and highways: $7 billion of the $9 billion appropriated for transportation primarily or exclusively serves car and truck traffic. As Brent Toderian frequently says: show me your budget and I’ll show you your priorities.

Downtown offices may be struggling, but dense, mixed-use neighborhoods are flourishing. Tracy Hadden Loh of the Brookings Institution’s Metro program has a thoughtful op-ed in the Los Angeles Times pushing back against the anti-urban “doom-loop” messaging that seems to dominate the media. Citing Brookings’ analysis of Census data, she notes that residential neighborhoods in cities are seeing renewed growth.

people are enjoying walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods where they can both live and work, in contrast to the 20th century mode of cities and suburbs that rigidly separates work zones from other activities.

Pointing to a series of Los Angeles neighborhoods that are flourishing, Loh says

Why are some neighborhoods doing extraordinarily well? These are not the richest parts of L.A. Rather, they gather big, diverse collections of economic, social, physical, and civic assets in close proximity

The common narrative about cities implies that the only reason people live in or near cities is to be close to places of work. The resilience of urban neighborhoods that offer a wide range of social, cultural, economic and consumption opportunities is evidence that cities are about much more than access to jobs.

In the news

StreetsblogUSA re-published our commentary on the “meh” of Carmaggedon in Philadelphia after the collapse of a section of I-95.