Since Covid started, rents are down in some cities, but up in most

“Superstar” cities have experienced the most notable declines; the demographics of renters in these cities are different than elsewhere.

Rent declines are also much more common in larger cities, with higher levels of rents.

City Observatory is pleased to publish this guest post from Alan Mallach. Alan is a senior fellow with the Center for Community Progress, known for his work on legacy cities, neighborhood change and affordable housing. His most recent book is The Divided City: Poverty and Prosperity in Urban America, and he is currently co-authoring a book on neighborhood change.

Alan Mallach

A lot of attention has been given to the decline in rents in a handful of high-profile superstar cities like San Francisco or Washington DC. But, as I’ve had occasion to observe in the past, those cities are only a handful among the hundreds of cities and housing markets across the United States. The real question is whether the trends observed in the superstar cities reflect broader national trends, or whether – once again – they are the outliers in a larger, more complicated picture.

To get a sense of the trends, I looked at rental data gathered by the website Apartment List (www. apartmentlist.com) by city, pulling out those of the 100 largest cities for which data was provided, supplementing it with data from smaller cities as well as metro-level data. I looked at the trend for all rental units between January 2020 and January 2021, and for comparison purposes, the preceding year. While far from a complete picture of the rental markets in the United States or even in these cities, it’s a useful starting point for an overall perspective on what’s going on. This short piece will try to highlight some initial findings and offer some suggestions about the mechanisms behind the trends.

The short answer is yes, they are outliers. More cities are still seeing increases in median rents than decreases in the face of the pandemic, by a ratio of roughly 3 to 2.

Figure 1: The 100 largest cities by rent change from January 2020 to January 2021

Still, the fact that over a third of all cities saw declining rents, and in many cases significant declines, is notable. The year before, rents declined in only 6 out of 95 cities, and in no case by as much as 2 percent.

Two clear patterns jumped out:

- The bigger the city, the more likely rents were to decline. Rents, on average, declined by 6 percent from January to January in the nation’s 10 largest cities. The only one where rents went up was Phoenix, while rents stayed flat in San Diego.

- The higher rents were before the pandemic, the more likely rents were to decline. Rents on average went up 2 percent in the 10 lowest rent cities but went down by a whopping 13 percent in the 10 highest rent cities.

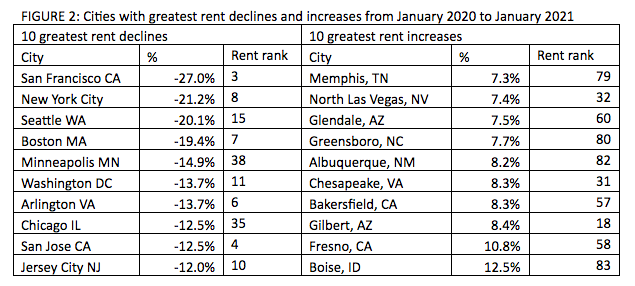

Looking at the ‘top 10’ and ‘bottom 10’ in terms of rent increases or declines, and how their January 2020 rent ranked out of 100 cities, shows an interesting pattern.

Of the cities with the greatest declines, most are recognizable as superstar cities, with Jersey City and Arlington being appendages – from a housing market standpoint – of New York and Washington respectively. Chicago and Minneapolis are less so, but both have seen extensive construction of upscale rental housing over the past 10 or so years. All but the last two are in the top rent quintile. By contrast, the cities with the greatest rent increases are medium-sized and smaller Sunbelt cities well outside superstar cities’ orbits. While these cities tend to skew toward moderately low rents, they are far from the lowest rent cities.

The following chart (Figure 2B) shows the relationship between the change in rent over the past 12 months and the average level of rents in January 2021. (The size of circles corresponds to the relative population of each city; hover over a circle to see the identity of each city and its rent level and rent change).

Figure 2B: Change in rents and rent levels, 100 largest US cities

What can explain this pattern? There may be a few factors at work. A major one is the difference in the character of the renter population. The cities with the greatest declines are cities where large numbers of renters are young and affluent, a market to whom those cities’ rental developers and landlords have been increasingly catering in recent years. Many of these renters appear to be moving – in part out of these cities, but also in part to homeownership in the same cities. Notably, the 10 cities with the greatest rent declines saw a simultaneous average 6 percent increase from December 2019 to December 2020 in Zillow’s Home Value Index. It also is likely to reflect a decline in in-migration of young, affluent renters, as suggested by recent research from the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, as the same reasons that have prompted out-migration have made in-migration, at least for the time being, less appealing.

Strong anecdotal evidence suggests that the declines are largely concentrated in the upscale or Class A rental market, as a recent report from WAMU in Washington DC noted,

“The drop [in rent levels] is driven primarily by price reductions in “Class A” apartments — newly-built units that have more luxurious amenities: Think buildings like The Apollo on H St. NE, or The Hepburn in Kalorama. As of October, the average rent for apartments like these dropped from $2,669 to $2,387 per month.”

It’s not surprising. Driven by Millennial migration, the upscale rental sector has been riding a wave for the past decade. Reflecting typical copycat developer behavior, upscale rentals have arguably been overbuilt in all of the cities seeing the sharpest declines in rent levels. Thousands of units have been built on spec, and with previous downtown workers moving out and fewer new workers coming in, vacancies increased and demand plummeted. Supply may eventually adjust to reflect lower demand, but that may take years.

In most cities, however, renters are mostly lower to middle income, which brings in another factor.

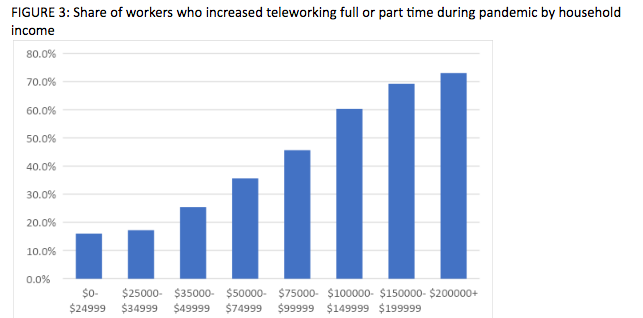

Upper income, highly educated workers are far more likely to have shifted to working from home during the pandemic than lower-income, less educated workers. As Figure 3 (from the Census Bureau’s Housing Pulse Survey) shows, two-thirds of workers in households with incomes over $100,000 (and nearly three-quarters of those with incomes over $200,000) have moved to full or part time telework, compared to little more than 15% of those earning under $35,000. The education gap is similar.

Source: Census Bureau, Housing Pulse Survey

With mortgage interest rates at all-time lows, affluent teleworkers can easily segue to homeownership. For a couple paying $2500 or $3000 in rent, a mortgage on a $600,000 house in a large, expensive city is only a moderate reach, and a $300,000 house in a smaller, attractive but more moderately priced city is a bargain.

Low wage workers, who tend to be concentrated in service, health care, distribution or other sectors where working from home is not an option and often lack the means to become homeowners, are less likely to move. Thus, cities like Cleveland or Des Moines, where renters are predominantly lower income households, are seeing little change in rental demand. What they are likely to see, although its impact will not be visible until well into 2021 or later, is growth in rental arrears, as thousands of lower income tenants who have lost their jobs find it impossible to make rent payments. Unless forestalled by adequately funded rental assistance, that could end up creating far more dire problems for far more people than rent declines in upscale San Francisco apartment buildings. The threat of evictions, however, is unlikely to lead to declines in rent levels, at least in the short run, as landlords try to compensate for lost rental income.

Few tears need be shed for the owners and developers of upscale apartment buildings in superstar cities. A correction was timely if not overdue. A more important question is whether the high-wage employment that drove the wave will grow back, or whether telework will become increasingly the norm. If the latter, not only are rents unlikely to revive, but the knock-on effects to the retail and service sectors supported by high-wage employment could be disastrous, with bars, restaurants, dry cleaners and other firms going out of business and thousands of lower-wage workers left unemployed.

If the markets in these cities can be considered losers, those of the secondary cities of the Sunbelt shown in Figure 2 may be considered at least so far the winners. Not only have they seen sharp rent increases, but they saw even greater sales price inflation, with house values going up an average of 13% in the past year, well above the national average. Boise, Idaho topped the charts with a whopping 21% annual increase, while, according to Albuquerque Business First, “the [Albuquerque] market shows no signs of slowing down, with homes going for record high prices and newly-listed property going under contract in less than 30 days.” Whether what’s good for the housing market in these cities is good for the people who live there, of course, is another matter.