ODOT’s proposed I-5 Rose Quarter project would turn a school yard into a freeway

The widened I-5 freeway will make already unhealthy air even worse

Pollution from high volume roads has been shown to lower student achievement

ODOT also proposes to build sound walls in Tubman’s school yard

Portland’s Harriet Tubman Middle School is one of the city’s most diverse. Located in the heart of what historically was the center of the state’s African-American population, more than 60 percent of those enrolled are students of color. The Harriet Tubman School has long been the focal point in the struggle against racist policies. Community activism helped save the school in the 1980s. There’s another historical legacy nearby as well: the Interstate 5 Freeway, which, as we’ve chronicled was rammed through the neighborhood in the early 1960s, and which triggered a two-thirds decline in Albina’s population in just two decades.

We’re looking at Tubman Middle School today because the Oregon Department of Transportation is proposing to double-down on the environmental insult done to the area by widening the I-5 freeway, moving it even closer to the school. As Oregon Public Broadcasting has reported, ODOT wants to move the freeway onto school property, and also build two 1,000-foot long, 22-foot tall noise walls between the school and the expanded freeway. On Friday April 9, 150 community members rallied at the school to oppose the freeway widening project. Two of the speakers were 9th grade students Adah Crandall and Malina Yuen, who had attended Tubman.

Moving the freeway closer to the school

When it was built in the early 1960s, the freeway sliced through a portion of the then Eliot School’s grounds, removing a portion of both the school yard and the adjacent Lillis-Albina Park. Plans for a wider I-5 Rose Quarter Freeway showed it would move the roadway closer to the school. The group No More Freeways commissioned the following video showing how the freeway would cut away the hillside between the current roadway and the school. No More Freeways filed suit in federal court to challenge the project’s environmental impact statement on April 2.

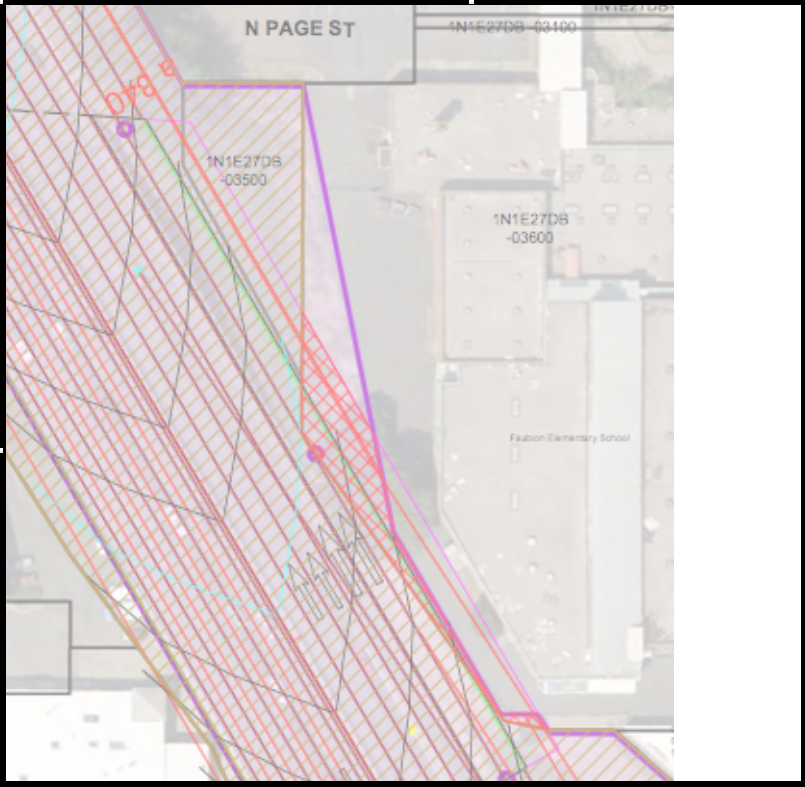

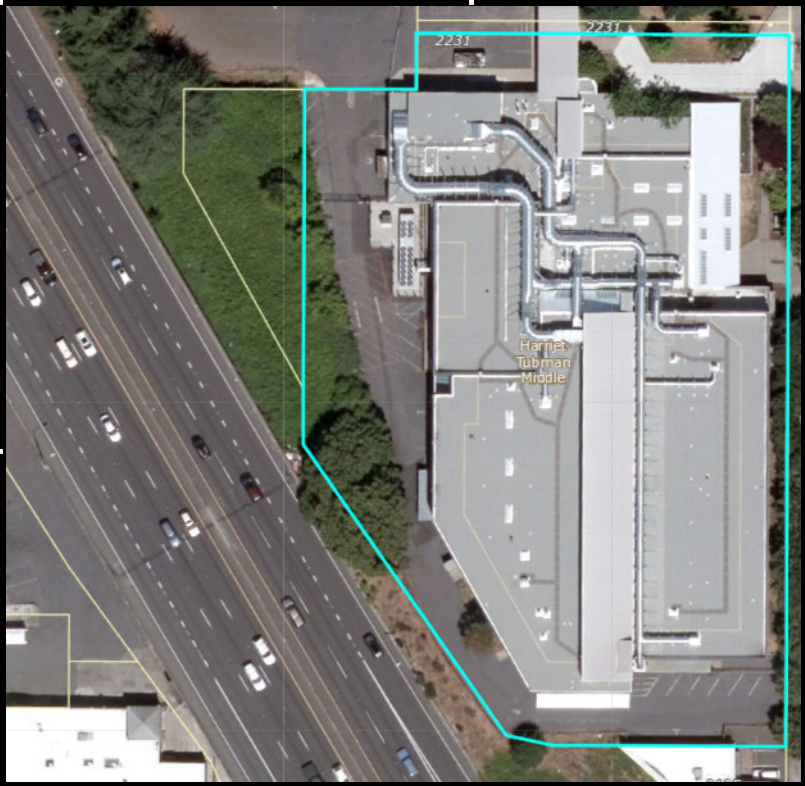

Taking School Property

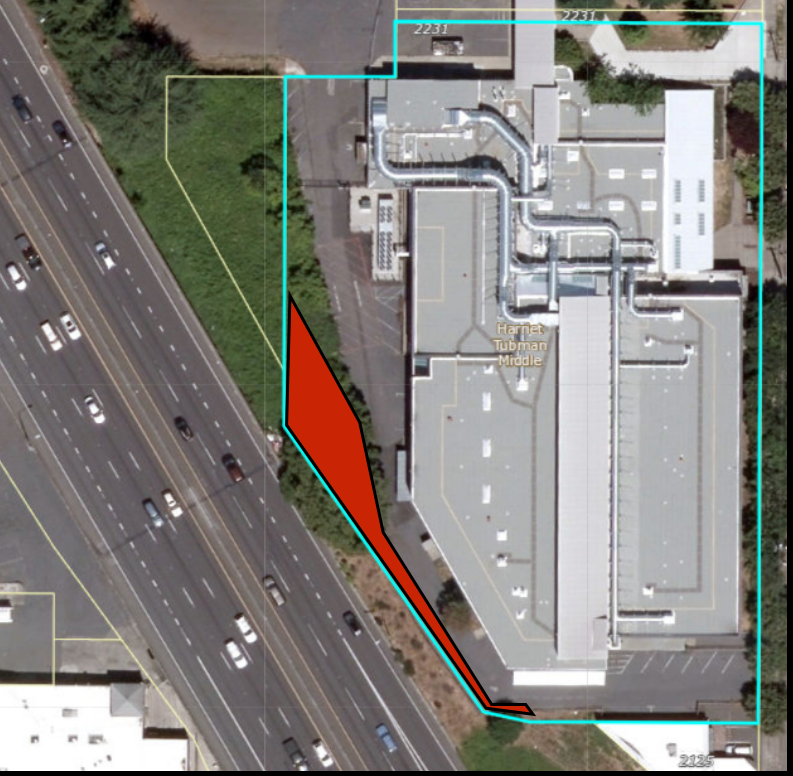

It hasn’t always been clear that the new freeway would intrude onto school property. Newly obtained documents, released as part of a public records request, show that ODOT intends to take property now owned by the school district for its expanded freeway. The following diagram shows the ODOT plans overlaid on a City of Portland map of property lines. The turquoise lines on the chart correspond to property lines. The red cross-hatched area on the diagram is school property that would be taken for the freeway.

[compare]

[/compare]

It’s a bit difficult to visualize the proposed taking of school property, so we’ve created a separate map which shows the take as a solid red area. It’s clear that the new, wider freeway will be built by expanding on Tubman School property. In a very real sense, we’re taking this land away from neighborhood school kids, and turning its use over to people driving through the area on the Interstate highway.

A wider freeway will worsen already unhealthy air at Tubman Middle School

The major environmental issue posed by the proximity of the I-5 freeway to Harriet Tubman Middle School is the air pollution from automobile traffic on the roadway. In its discussion of the issue, ODOT has been deceptive and inaccurate, both in estimating levels of pollution, and describing the standards of review required by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA).

ODOT has dramatically understated the air pollution associated with the freeway widening for several reasons. First, as we’ve pointed out, it has modeled traffic only for a six-lane freeway, when in fact the 160 foot roadway it is building could accomodate 10 lanes, and vastly more traffic. Second, its traffic modeling made factually false assumptions about both baseline and no-build levels of traffic on I-5 (inflating them by assuming that the Columbia River Crossing had been built in 2015 and allowing the model to have volumes in excess of capacity in the no-build scenario). Third, it understated the amount of traffic growth (and pollution) in the build scenario, because its modeling made no allowance for induced demand from added capacity.

In addition, ODOT (and its peer review panel) engaged in a bit of regulatory sleight-of-hand in characterizing the project’s air quality impacts. First, ODOT has repeatedly claimed that air quality in the area will be better in the future under the build scenario than it is today. That may be true, but if it is, it is only because of factors entirely external to the project, specifically a changing vehicle mix (i.e. assumptions that fossil fueled vehicles become cleaner due to fuel efficiency requirements, and that a larger fraction of the fleet is electrified). Whether this is true or not, it is actually irrelevant for purposes of the analysis required under NEPA. NEPA requires a comparison of environmental effects with and without the project (i.e. “build” vs. “no-build”). Since we will get vehicle efficiency and electrification regardless of whether this project is built or not, the fact that pollution levels are less than today (or not) are irrelevant. The real, and unanswered (or incorrectly answered) question is whether air pollution will be higher under the “build” scenario, rather than the “no-build” scenario. As we enumerated above, because ODOT systematically over-estimated “no-build” traffic, and systematically under-estimated “build” traffic, it got that analysis wrong. Application of a scientifically calibrated induced travel calculator to the project shows that widening I-5 will generate millions more miles of car travel and thousands of tons more greenhouse gases and pollution each year.

The second bit of sleight of hand is claims by ODOT and its peer review panel that the project is either in compliance with the Clean Air Act or that no analysis of this project is required by the Clean Air Act (CAA). That’s interesting information, but for the purposes of complying with NEPA, is irrelevant. NEPA requires a disclosure of a project’s environmental impact, not simply an assurance that the project hasn’t violated some other federal law. The peer review panel maintains that because Portland is not a “non-attainment” area under CAA, that ODOT is not required to do a “hot spot” analysis of the project. The panel and ODOT also maintain that because no regulatory standards exist for greenhouse gas emissions, the project need not consider them. Again, this may be true under the Clean Air Act, but by omitting this information, ODOT is failing to meet its obligations under NEPA to reveal the environmental effects of the measure. In addition, NEPA requires that a project demonstrate conformity with applicable state and local laws; Oregon statutes call for an 80 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions statewide by 2050, and nothing in the project’s environmental assessment indicates how this project would comply; again, estimates using the induced travel calculator indicate the project will generate 8-15,000 additional tons of greenhouse gases annually.

Third, and perhaps most important, none of this analysis indicates whether either current or future levels of air pollution at Tubman School will be healthy or tolerable for Tubman students, staff and the public. Even at current traffic levels, Tubman School’s air quality is problematic. An independent assessment advised the school district to restrict outdoor activities by students. The district spent more than $12 million of its own funds to add air filtration to make air inside the building safe for students to breathe. Portland School Board member Julia Brim-Edwards raised exactly this issue at the March 22, 2021 meeting of the Executive Steering Committee. In reply, she was told by members of the peer review panel that they didn’t look at that issue and that they were only tasked with judging compliance.

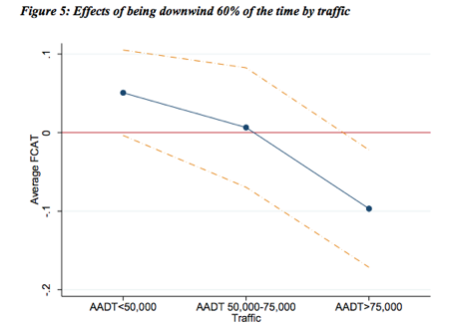

It is entirely possible for a freeway-widening project not to violate the Clean Air Act but also to worsen air pollution in a way that is deleterious to the health and well-being of people near the freeway. We have a growing body of scientific evidence that higher levels of traffic near schools tend to impair student performance. A recent study published by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that after controlling for a variety of other factors, proximity to high volume roadways (like I-5) had a statistically significant negative effect on student performance on standardized assessment tests. According to ODOT, this stretch of road carries about 120,000 vehicles per day, putting in the highest category on this chart, and the expansion project would allow even more cars in this area.

Jennifer Heissel, Claudia Persico, David Simon,

Does pollution drive achievement? The effect of traffic pollution on academic performance.

NBER Working Paper No. 25489.

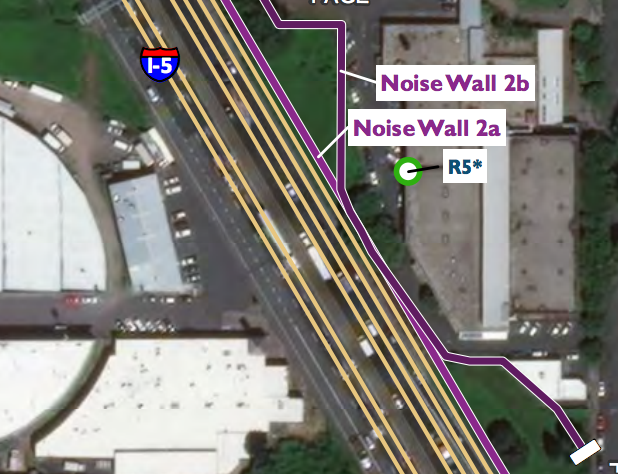

A closer freeway means more noise pollution and towering sound walls

But ODOT isn’t just going to take school property for the freeway. It is also proposing to build two 1,000-foot long, 22-foot tall noise walls between the newly widened roadway and the school. In the following ODOT diagram—taken from the project’s 2019 environmental assessment—the two walls are shown as “2a” and “2b” and are shaded purple.

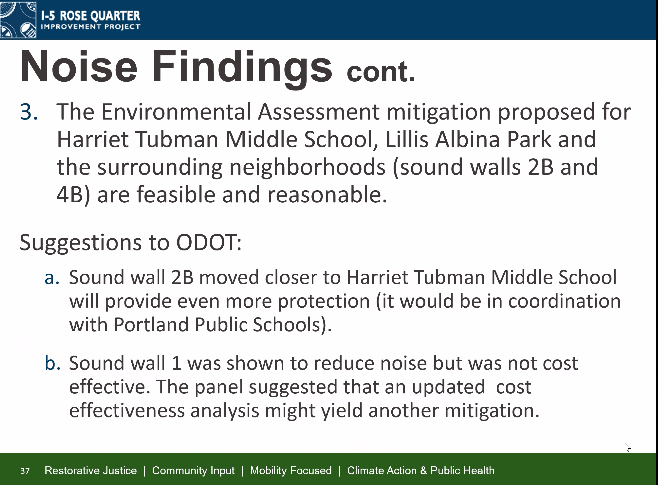

The exact location of these noise walls doesn’t appear to be final. The plans are a bit vague as to whether they’ll be built on ODOT property or on the school grounds. In theory, the walls are supposed to attenuate the noise from the closer, wider freeway at the school. In fact, ODOT’s own peer review panel raised concerns about whether the walls would be effective, and recommended that the walls be moved closer to Tubman School. This would almost certainly mean that the walls would be built on school property—so in addition to having some of its land taken for the roadway, the panel’s recommendation is that a further portion of school property be taken for the noise wall.

The two twenty foot walls will be roughly as tall as the Tubman building itself (and are nearly twice as tall as the Berlin Wall), while they might reduce sound somewhat, they’ll also turn the school’s grounds into a cramped area dominated by a 1,000 foot long concrete wall, arguably more like a prison yard than a school yard.

Making a mockery of equity and restorative justice

As we’ve made clear at City Observatory, decades of highway building by the Oregon Department of Transportation decimated the Albina neighborhood, leading directly to a decline of two-thirds in the neighborhood’s population (the leading to the Eliot School—original occupant of today’s Tubman building—being merged with the nearby Boise School, because of falling enrollment. The Oregon Department of Transportation’s I-5 Rose Quarter Freeway widening project benefits car travelers, particularly suburban commuters, while imposing significant financial, health and learning costs on Tubman students. While the average peak hour single occupancy car commuter from Clark County Washington has a median household income of $82,000; half of Tubman students are on free and reduced price lunches. In addition, three quarters of those commuters a non-Hispanic whites, while two thirds of the Tubman student body is children of color. The $800 million project will subsidize these car commuters, and meanwhile Portland Public Schools has had to spend $12 million (that could otherwise be spent improving education) on making the air in the school building fit to breathe. These stark disparities in who bears the costs and who gets the benefits of this freeway widening make a mockery of its claim to be promoting “restorative justice.”