2020 was a trying, tumultuous and often tragic year. Here are some of the top commentaries that marked the year.

Like so many, we were preoccupied with global crisis of the Covid-19 pandemic. Early on there was a chorus of voices blaming cities and urban density for the rapid spread of the pandemic. We pushed back with a string of analyses debunking the density theory. We also punctured a related series of anecdote driven claims of urban flight. As it turns out some of the densest places in the country (and the world) weathered the pandemic well, while the worst outbreaks were in rural areas. Initially, poverty and housing overcrowding, not urban density were the strongest correlates of viral spread.

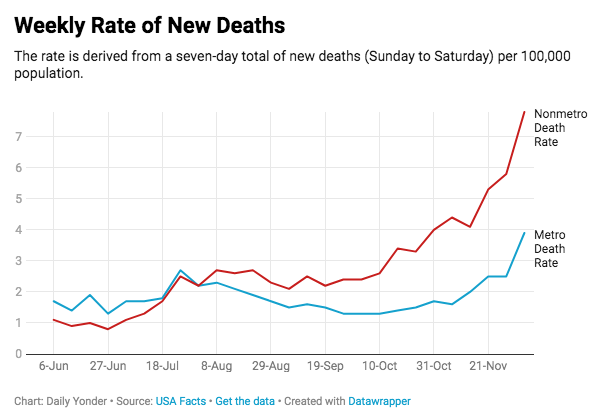

In the summer and fall, as the pandemic worsened dramatically in its second and third waves and was far worse in rural areas than in the nation’s large cities. With the pandemic becoming universal, low density and sparse population were no protection from the virus.

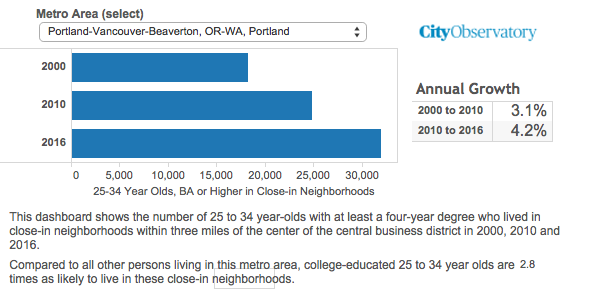

In June, we released our latest CityReport: Youth Movement, chronicling the latest data on the movement of well-educated young adults to the close-in urban neighborhoods of the nation’s largest cities. We found that the number of 25- to 34-year-olds with a four-year or higher degree living within three miles of downtown increased in every one of the 52 largest metro areas, and moreover that the rate of increase accelerated in 80 percent of these large metro areas since 2010.

The death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police provoked a wave of national revulsion and a reawakening of the unfinished conversation about racial justice. We refreshed our analysis of racial segregation in the nation’s large cities, ranking the most and least segregated cities. We’ve also explored the ways that our current transportation system discriminates against the poor and people of color. There’s much work to be done to make our cities more just and inclusive.

Even though the pandemic and associated lockdowns and recession produced a decline in vehicle miles traveled (and even a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions), they didn’t make our roads safer, as speeding worsened, and traffic fatalities increased. We challenged the notion that spending money for elaborate and circuitous pedestrian overpasses actually promotes walkability, arguing that these structures are really to benefit cars, not people walking.

In our home base, Portland, the proposed I-5 Rose Quarter Freeway widening project has ballooned in cost—as we predicted—to nearly $800 million. We identified more than two dozen reasons, from safety, to climate, to racial justice, to bike and pedestrian access, to better air quality, as to why this expensive folly shouldn’t go forward. And 2020 marked a dramatic shift in the project’s political fortunes, as key community groups and city leaders came out in opposition.

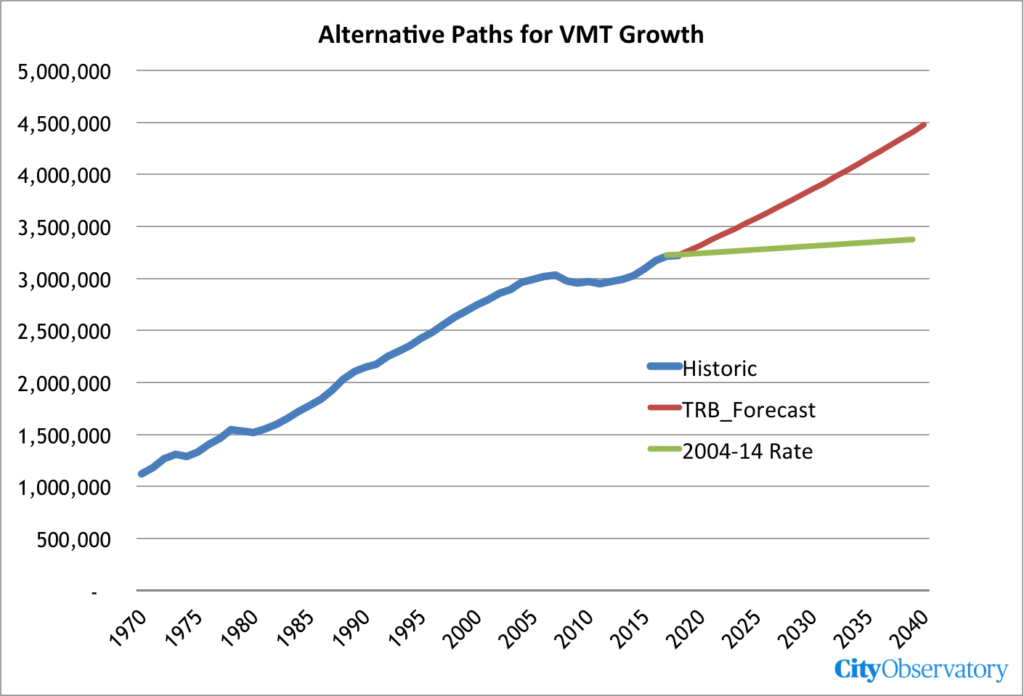

Portland’s freeway battle is just a microcosm of an emerging national battle over whether we’ll continue the expansion of urban freeways, which will generate even more travel, sprawl, and greenhouse gas emissions. Tragically, groups like the Transportation Research Board are implicitly endorsing climate arson with reports that call for vastly expanded subsidies to road construction and driving, something we called out in our essay “highway to hell.”

Cities will have important decisions to make in the coming year about whether to continue down the path to a worsened climate crisis, or whether to begin reducing car dependence. We and others are optimistic that building great urban spaces is a foundation of a sustainable and just solution to the climate crisis.

Housing affordability continues to be a widespread concern. Unlike previous recessions, the Covid recession has been marked by a robust housing market with rising home prices. Concerns about affordability in some city neighborhoods inevitably touch on gentrification. Two of our most-read commentaries in 2020 summarized the latest research findings on neighborhood change (long time residents benefit from gentrification), and constructing more new housing tends to hold down rents. While gentrification generates popular press, its still the case that concentrated poverty and neighborhood decline are vastly more widespread and destructive.

Looking forward to 2021, many people are worrying about the fate of cities. Despite the pandemic, we’re optimistic that the same powerful forces that have driven city dynamism and success will re-assert themselves. In a long essay looking forward, we argued that seven “C’s” are likely to buttress urbanism in the years ahead. We think people are too quick to assume that the work-around of work-at-home will displace the power of face-to-face interaction, which happens best and most in cities. In particular, we argue that the competitive nature of the workplace and labor markets advantage those who are in the office, and disadvantage those who are at a distance, a fact that’s not apparent when everyone is forced to work from home, but which will change as people are able again to return to the office. And beyond that, going to work is far from the only (or even the most important) reason people choose to live in cities. The personal, social, and consumption opportunities of cities continue to be a powerful draw, especially for well-educated young adults. We suspect that as the pandemic fades a large, pent-up demand for close personal interaction will powerfully stimulate urban economies. Once again, we’ll want to be in the “room where it happened” and won’t settle for being digital bystanders on Zoom.

As Covid-19 vaccines become more widely available in the new year, we’ll be looking for a resurgence of more normal activities, including city living. We’ll be watching in 2021. Happy New Year!