The Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) desperately wants to build a mega-freeway through NE Portland, and is planning to double the freeway from 4 lanes to 8 or 10 lanes. But it has hidden its true objective, by claiming only to add two “auxiliary” lanes to the existing 4 lane freeway, and arguing (falsely) that these lanes won’t increase traffic. But when you look closely at its sketchy information revealed in its Environmental Assessment, it’s actually building a 160 foot right of way, easily wide enough to accommodate 8 or 10 full traffic lanes. Recent modifications to the I-5 project design on a viaduct section of the project, where ODOT is going to re-stripe the freeway rather than widen the viaduct to add a lane, shows that ODOT can easily squeeze 8 or even 10 lanes into the project. That’s important because the project’s environmental assessment has neither considered the traffic and pollution from an eight lane freeway, or explained why the right of way needs to be vastly wider than needed to accommodate the supposed 6 lane configuration the agency says it is building.

- The Rose Quarter freeway widening is now narrower, which shows ODOT has wide discretion to re-stripe lanes and shoulders to add capacity

- To avoid intruding on the Eastbank Esplanade, ODOT has dropped its plans to widen the viaduct overhanging the pathway, but will squeeze in another lane of traffic by re-striping the existing 83′ wide viaduct.

- At the project’s key pinch point, the Weidler overpass, ODOT is engineering a crazy-wide 160 foot wide roadway ostensibly for just for six travel lanes. But this roadway is more than enough to fit 8 or even 10 lanes of traffic, just by striping it as they are now planning to stripe the viaduct section of the project.

- ODOT’s environmental analysis has violated NEPA by failing to consider this “reasonably foreseeable” eventuality that ODOT will re-stripe the project to 8 or more lanes, which would produce even more traffic, air pollution and greenhouse gases, impacts that are required to be disclosed.

- ODOT has also violated NEPA by failing to consider a narrower right of way: 96 feet would be sufficient to accommodate its added “auxiliary lanes” and would have fewer environmental impacts and lower costs.

- ODOT’s safety analysis for its narrowing of the viaduct section shows that narrower lanes and shoulders make almost no difference to the crash rate, and further show that the project’s claims that it would reduce crashes on I-5 by 50 percent are exaggerated by a factor of at least seven. The analysis also shows that the project has a safety benefit-cost ratio of about 1 to 200, meaning it costs ODOT $2 for 1 cent of traffic crash reductions, about 2,000 times less cost-effective that typical safety projects.

- The safety analysis also confirms that ODOT made now allowance for the effects of induced demand: It makes it clear that the project assumed that traffic levels would be exactly the same in 2045 regardless of whether the freeway was expanded or not.

In a seemingly innocuous appendix to its Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI), ODOT has tipped its hand: It’s really building the right of way for an 8- or 10-lane freeway at the Rose Quarter. The reason this project’s budget has ballooned from $450 million in 2017 to $1.45 billion today is because they’re not simply adding a single so-called “auxiliary” lane, but instead are doubling the freeway’s footprint as it cuts through North Portland.

ODOT narrows part of its proposed I-5 freeway to protect a park

ODOT had a problem with the Eastbank Esplanade. It’s a linear parkway that between the Willamette River and I-5. The original proposal for the freeway widening project called for this section of freeway, which rises on a viaduct, to be widened into the park. Unlike other requirements of NEPA, which are essentially procedural, and only require disclosure of impacts, provisions pertaining to parks have real teeth. Expanding highways onto public park lands has to comply with tougher requirements under what is called Section 4(f).

ODOT initially tried to conceal the intrusion of the widened freeway viaduct onto the Esplanade. The agency didn’t publish detailed design drawings as part of the Environmental Assessment. It produced these preliminary engineering plans only after threat of legal action (and after denying that they even existed). The plans became available only days before the deadline for public comment on the project EA. Even then, it took sleuthing by project opponents to discover and document the widened viaduct.

A widened viaduct would have extended over the Eastbank Esplanade. Illustrations produced by Cupola Media from data suppressed by ODOT. (Bike Portland)

A widened viaduct would have extended over the Eastbank Esplanade. Illustrations produced by Cupola Media from data suppressed by ODOT. (Bike Portland)

Recognizing that they were unlikely to meet the 4(f) requirements, or would be dramatically delayed by doing so, ODOT project engineers decided to simply lop off the viaduct-widening portion of the project. Instead of widening the viaduct section to 105 feet, ODOT will simply re-stripe the existing 83 foot wide viaduct section with narrower lanes and narrower shoulders. (Lane width data calculations shown in Appendix, below). And apparently, they decided this very recently: The safety analysis for the new narrower viaduct section memorandum is dated October 6, 2020 and was last revised on October 23, 2020, only a week before the FONSI decision (dated October 30, 2020). (This document now appears in the Rose Quarter Library here).

Because it is not widening this 1,200 foot stretch of the I-5 freeway, but wants to add another travel lane to I-5, ODOT has now decided that it can have both narrower shoulders and narrower vehicle travel lanes on this stretch of the freeway. Here is its description of current conditions (the No Build-83′), the revised plan (“Scenario 1”-also 83′), and the widened viaduct originally proposed in the EA (“Scenario 2”-105 feet).

This decision and its supporting analysis proves two key points:

First, that ODOT can and will re-stripe existing roadways to provide more capacity, and there’s nothing about their regulations, engineering practice or concerns about safety, that preclude them from doing so. The memorandum essentially argues that there’s only a minor increase in crashes as a result of the lane and shoulder narrowing, and that this is acceptable. It also notes that a “design exception” will be required, but that’s in no way a barrier to undertaking this action. (In essence, if it’s necessary to avoid an environmental impact, ODOT believes it has complete flexibility to make an exception to its design standards to narrow both lanes and shoulders).

Second, the safety analysis presented here undercuts all of the overblown claims that widening I-5 is a “safety project”—time and again, ODOT officials have cited the inadequate width of the freeway and its narrow shoulders as safety problems. All this is was a big lie, as we and other independent observers have documented.. And ODOT has even conceded that we were right in our critique. But this new analysis shows that the crash reduction from wider roads is trivial. The analysis estimates the value of crash savings from the project $400,000 per year. (Never mind, for a moment that these estimates are almost certainly wrong because they are computed using an ISATe model that explicitly says that it cannot be used to compute crash rates for freeways with ramp metering, which this section of I-5 has). Even relying on ODOT’s own calculations, the safety benefits of this project are negligible, so much so, that ODOT has no trouble narrowing both lanes and shoulders in a significant section of the project.

Why is this 6 lane freeway 126 feet wide? ODOT’s real plan for an 8-lane freeway

Nearly two years ago, we called out ODOT for failing to disclose that what it was proposing to build at the Rose Quarter was really a massive, eight-lane freeway. It was engineering a broad right-of-way, that with a few gallons to paint, could easily be striped to provide 8 full travel lanes, four in each direction, essentially doubling the capacity of the roadway through the Rose Quarter.

Forget for a moment the labels ODOT attached to lanes, and look, simply at the actual width of the highway right of way they are proposing to build. Take out your tape measure, and follow along. From curb to curb at the NE Weidler overpass, they’re planning to widen the freeway’s footprint from 83 feet to 126 feet. It’s actually a challenge to figure out how wide the freeway is and how much wider it’s going to be, because ODOT consciously chose to exclude that data from most of the project’s Environmental Assessment.

Currently, most of the corridor is 83 feet wide. This image, taken from Google Maps, show cross-section of the existing I-5 freeway, just south of the key Weidler overpass, As Google Maps scale measure indicates, this freeway cross sections is approximately 83 feet wide.

ODOT has not released detailed cross-sectional plans of what it proposes to build. The project’s Right of Way technical report, has this crude illustration of existing and proposed widths. Note that in the “Existing conditions” section, ODOT has left out the width of inside and outside shoulders (“varies”), which obscures the exact width of the overall cross section, which we know from Google maps to be 83 feet at the Weidler overpass.

The proposed width of the I-5 freeway can be calculated (roughly) from the ODOT diagram. If we add together the travel lanes, the shoulders and an allowance for the width of the median barrier, we get roughly 126 feet—six 12-foot travel lanes, four 12-foot shoulders and an additional six feet for the width of the barrier (72+48+6=126). (See Appendix below for additional detail).

Why, might you ask, has ODOT selected 12-foot inside and outside shoulders? No explanation is provided for this exact choice in the EA. (ODOT asserts that wider shoulders are needed for “safety”—more about that claim below—but that doesn’t explain the choice of 12 feet. In fact, 12 feet is vastly wider than any shoulder width on an urban stretch of I-5 anywhere in the City of Portland. Typical shoulder widths are 4-8 feet.

The real reason for these excessively wide shoulders is to allow ODOT to re-stripe this section of freeway at some future date to allow eight lanes of traffic. Here’s how.

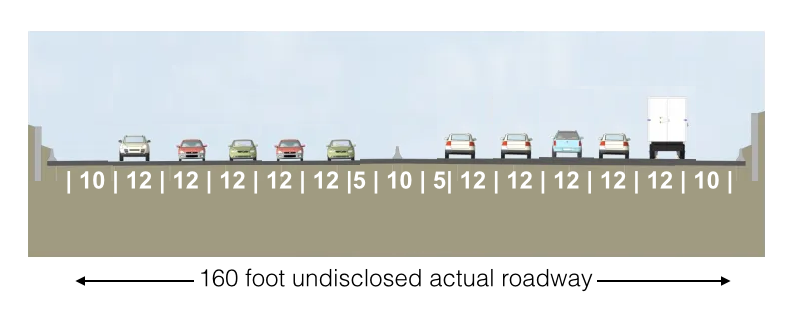

A 126 foot right of way can easily accommodate 8 lanes of traffic. Here we’ve juxtaposed ODOT’s illustration of the proposed freeway cross-section with six traffic lanes from the EA, with a revised version that adopts the shoulder widths ODOT has adopted for the revised viaduct section.

These shoulder and lane width measurements for this potential future re-striping are taken directly from ODOT’s own memorandum describing its revised design for the viaduct section of the I-5 freeway. We’ve simply applied these same measurements—6.5 foot outside shoulders, 4 foot inside shoulders and a mix of 11 and 12 foot travel lanes—to this 160 feet of right of way. We even have about 8 feet of roadway left over. The point is that ODOT has proposed to construct a roadway that could easily be reconfigured to carry eight or ten lanes of traffic with a few gallons of paint.

Re-striping for 8 or 10 lanes is a reasonably foreseeable event

Not considering the possibility that a wider I-5 could be re-striped for 8 or 10 lanes of traffic is a violation of the National Environmental Policy Act’s requirement that the agency disclose and evaluate the cumulative impacts of reasonably foreseeable future events.

ODOT’s analysis of the environmental effects of the Rose Quarter project is based on the premise that there are only six lanes of freeway capacity through the Broadway-Weidler section of the I-5, and that widening the road to from four to six lanes in this area will have no effect on freeway traffic volumes. (This flies in the face of what we know about induced demand).

But more to the point: the EA failed completely to consider the traffic and environmental effects of an eight- or ten-lane freeway. And because the project is constructing a 160-foot right of way, it has more than enough room to increase the freeway to 8 or 10 full travel lanes with even wider shoulders than it is proposing on the re-striped viaduct section. This is important because, having built such a wide right-of-way, it is in fact “reasonably foreseeable” that in the future, ODOT will fire up its paint trucks and re-stripe this section of the freeway—just as it has effectively done with the revised plan for the viaduct section.

It doesn’t matter whether ODOT has “no current plans” to widen the freeway to 8 or 10 travel lanes or not. The agency’s intent is not the legal standard. The standard instead is whether it’s reasonably foreseeable that an agency might do so. Given that they designed a right-of-way easily wide enough to handle eight or ten lanes, and that the agency’s own analysis shows neither lane widths nor shoulder widths make much difference to safety, and that the agency is willing to re-stripe an existing section of the same roadway to accommodate more traffic, and that the sponsoring agency, FHWA, regards such restriping projects as a “best practice”—even holding up ODOT’s work as a national example—it’s quite clear than one can reasonably foresee that once this project is built at its much larger scale, with wider shoulders than found anywhere else on the urban sections of I-5, that in the future the agency may re-stripe it to eight or ten through travel lanes.

What NEPA then requires is that ODOT evaluate the likely environmental impact of an eight- or ten-lane freeway in this area—something it simply hasn’t done. If it analyzed the impact of an 8- or 10-lane roadway here, it would get much higher traffic counts, many more vehicle miles traveled, more air pollution and greenhouse gases. These are exactly the kinds of impacts that ODOT is required to reveal as the likely “cumulative impact” of their chosen project—and they have not done so. This omission alone should force the agency to conduct a full Environmental Impact Statement.

Why build 160 foot freeway? Why not much narrower and less disruptive?

ODOT has also violated NEPA for failing to consider a narrower right of way through the project area. What remains completely unexplained and unexplored in the EA is why, assuming it needed only six lanes, the agency elected to build a 160 foot wide right of way. This will be extremely expensive, both for additional land acquisition and construction costs. If it were truly interested in only a six-lane cross-section, the right of way, using ODOT’s own standards (from the viaduct section), would only need to be 96 feet wide (See Appendix for calculation). That smaller cross-section would be cheaper to build and would have fewer environmental impacts, both because it would be less disruptive to existing adjacent uses like Harriet Tubman Middle School, but also because it would foreclose the future risk of the freeway being widened to eight lanes. ODOT’s own engineering consultants, ARUP, have said that the project could be at least 40 feet narrower than what ODOT is proposing if the need is for a total of six travel lanes. Again, the purpose of NEPA is to force agencies to consider a range of options, and present objective information on the relative environmental consequences of different options. By not looking at a 96-foot (or similarly narrower) right of way for the widened freeway, ODOT has violated NEPA.

In addition, the much wider freeway right of way makes it much more difficult and expensive to construct freeway covers that would support buildings, as some in the community are calling for. The reason is that a 160 foot freeway footprint would require spanning a 80 foot clear area (assuming that supports are built on the side and in the median of the freeway). If the freeway were only wide enough for 3 lanes, plus the type of shoulders ODOT is now proposing for the viaduct, the clear span distance would be about 50 feet. It would also reduce the cost of the project—less excavation would be required, overpasses and other structures would not have to be as large.

Widening the I-5 Rose Quarter does virtually nothing for safety

In theory, one reason that ODOT could argue that they need a 160 foot right of way for the Rose Quarter is safety. But this new safety memorandum disproves that point. It argues that shoulder widths of as little as 4 feet and narrower travel lanes make almost no difference to the safety level of I-5.

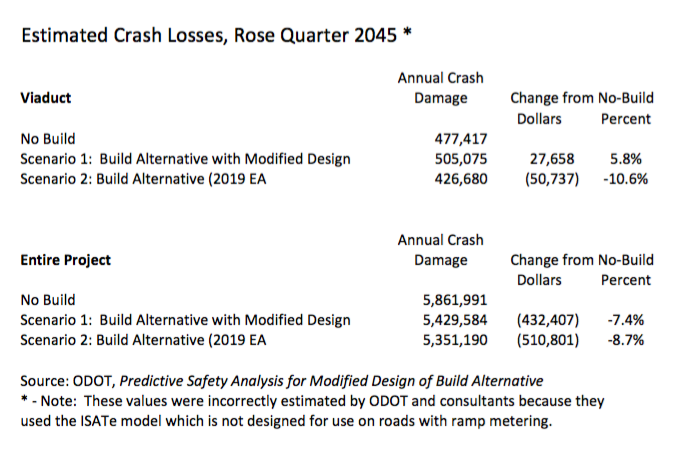

ODOT’s consultants say they have used the “Enhanced Interchange Safety Analysis Tool (ISATe)” model to estimate crash rates under the No-Build scenario, and for the original and modified build alternatives (i.e. with and without a widened viaduct section). This analysis claims that narrowing the lanes on the viaduct section would actually increase crashes on that section of the highway, increasing annual damages by about 6 percent over No-Build levels. Implicitly, ODOT is saying that when there are environmental concerns—in this case the intrusion of the freeway onto the Eastbank Esplanade—safety is here is no big deal and it’s perfectly justifiable to shrink the freeway shoulders and lane widths.

It’s also important to note in passing, that the ISATe model is not valid for making estimates of crash rates or crash changes on I-5. The model’s methodology explicitly states that it does not apply to freeways with ramp-metering. Ramp meters smooth traffic flow and tend to dramatically reduce crash rates. ODOT and its consultants erred in using this model to estimate and make claims about the I-5 project.

Overall, the safety memo concludes that the $1.45 billion dollar project in total reduces the dollar value of crashes in the area by about 7.5 percent, from about $5.9 million per year to about $5.4 million per year. Not only is this a very small (and speculative) reduction in the economic cost of crashes on I-5, the magnitude of these crash losses is tiny, especially relative to the cost of the project. Total savings of the project with the modified design are about $432,000 per year, compared to a project cost of roughly $1.45 billion. At a 5 percent discount rate, the $432,000 in annual crash savings has a present value of about $6.6 million, meaning that this project has a benefit cost ratio of less 1 to 200, i.e. you have to spend 2 dollars to get one cent in benefits. This is an extraordinarily poor return on investment.

This analysis shows that ODOT made false claims about the safety effects of the project. Project materials claim that the project will reduce crashes by up to 50 percent. The Project’s website claims that the project’s added lanes and wider shoulders will speed the flow of traffic and concludes:

Adding these upgrades is expected to reduce crashes up to 50 percent on I-5 . . .

It has gotten this same claim repeatedly published in the media by Willamette Week, The Columbian, and the Portland Tribune, and ODOT officials have testified to the same to the Oregon Legislature.

These data show that the change in crashes will be less than 10 percent. This means that ODOT’s claims that the project will reduce crashes by as much as 50 percent overstate the reduction by a factor of seven (a 7.4 percent reduction is roughly one-seventh of a 50 percent reduction).

In addition, these crashes are overwhelmingly non-injury fender-bender crashes. They’re not the crashes that regularly occur on ODOT highways in the Portland area that maim and kill hundreds of Oregonians each year.

Judged as a safety project, the Rose Quarter is an incredible waste of resources. ODOT runs a competitive safety grant program “All Roads Transportation Safety (ARTS)“. Typically the projects that are awarded funding have benefit cost ratios well above one. The top nine Region 1 projects awarded in 2018 had benefit/cost ratios of more than 10 to 1, meaning they are about 2,000 times more cost effective than the Rose Quarter freeway widening as a “safety” project.

Proving ODOT failed to consider induced demand

The ODOT safety analysis sheds some light on an issue that ODOT has long concealed: whether the project considered the effects of induced travel. A robust and growing body of scientific literature has confirmed the “fundamental law of road congstion”: expanding urban roadways tends to encourage more driving. The best estimates are that a one percent increase in freeway capacity leads to a one percent increase in vehicle miles traveled. ODOT has made vague claims that its modeling somehow dealt with this issue, but the safety report shows that ODOT either completely discounted or ignored induced travel. At two points, the safety report states that traffic levels on the viaduct section of the Rose Quarter project will be the same whether one lane is added, or whether the freeway stays its current width. In three separate locations, the memorandum states:

AADT [annual average daily traffic] is the same for all scenarios

Here’s a screenshot that explicates this assumption:

What the safety analysis is saying is that whether the freeway has five lanes or four in this cross-section it will carry exactly the same number of vehicles. That’s contradicted by the induced travel science, which suggests that a 50 percent increase in freeway capacity (from two lanes to three) will likely lead to a 50 percent increase in vehicle travel. This is important, because if traffic volume increases, that will more than offset the gains from the small reduction in the rate of crashes. By ignoring induced travel, the safety analysis understates the number of crashes associated with the build alternative.

Appendix: Analysis of Freeway Width, I-5.

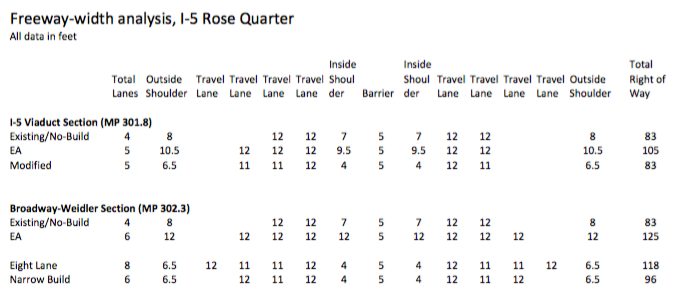

The following table shows the estimated width of the I-5 freeway, as currently built, and as proposed to be constructed as part of the I-5 Rose Quarter freeway widening project. These data are estimated from the EA Right of Way Report, the Predictive Safety Analysis Memorandum and Google Maps as described in the text above.

While it has done this analysis for the viaduct section, the EA has no analysis of an alternative with a narrower cross section through the Broadway-Weidler section of the project. If ODOT were to narrow this section of the project to 96-feet from 126 feet, it would reduce the impact on adjacent properties.