Restorative Justice & A Viable Neighborhood

What destroyed the Albina community? What will it take to restore it?

It wasn’t just the freeway, it was the onslaught of cars, that transformed Albina into a bleak and barren car-dominated landscape.

In the 1950s, Portland’s segregation forced nearly all its African-American residents to live in or near the lower Albina neighborhood. During that decade, Albina was one of the cities densest neighborhoods, full of houses, apartments and local businesses. In the late fifties and early sixties, the construction of Memorial Coliseum, urban renewal and finally, the I-5 freeway all triggered the neighborhood’s decline. Everyone now acknowledges that the construction of the I-5 Freeway through Albina was a classic example of the Oregon Department of Transportation’s institutional racism.

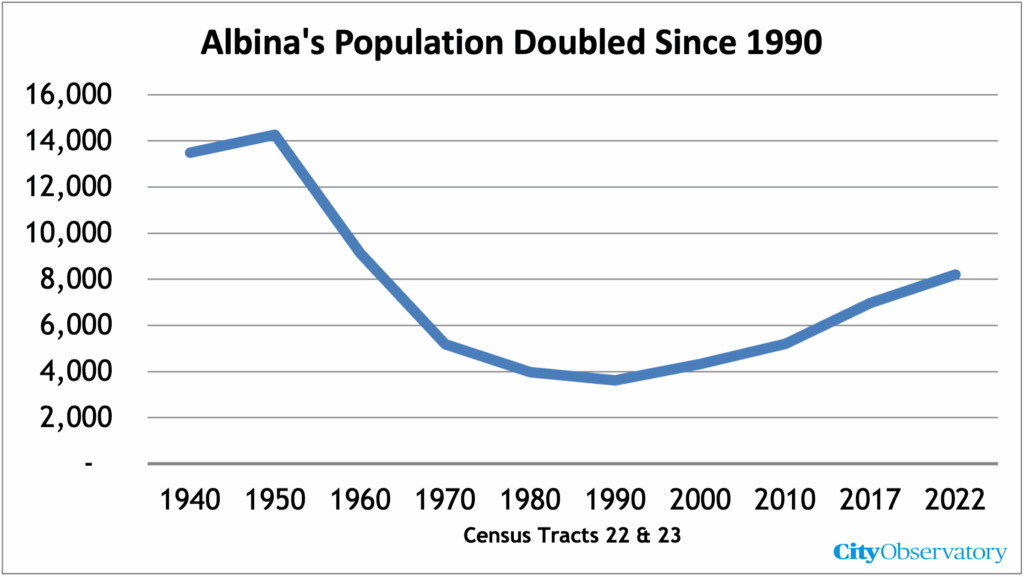

The construction of ODOT’s freeways triggered a wave of demolition and abandonment that caused the neighborhoods population to fall by two thirds. To be sure, ODOT demolished hundreds of homes. But the coming the the freeway and a flood-tide of cars traffic swept away the remaining population of the neighborhood.

The big question going forward is how to right that wrong. If we’re seeking restorative justice, what will it take to make a viable neighborhood?

It was the cars, not just the freeway, that destroyed Albina

It wasn’t so much the freeway that undermined the health of the neighborhood as all the cars the freeway brought. A better place for cars means a worse place for people.

Construction of the freeway was only part of the problem. Yes–the freeway wiped out more than 300 houses as it sliced through North and Northeast neighborhoods. But the real damage was done after construction was complete: it was the flood of cars, chiefly suburban commuters and shoppers that transformed the area from a viable neighborhood, to a car-choked collection of parking lots, gas stations, and auto-oriented businesses. Most of the decline in population in Albina happened years after the freeway was built. The flood of cars undercut neighborhood livability, and population steadily declined in the 60s, 70s and and 80s. As people moved away, neighborhood businesses that served local residents, many owned by African-Americans, died. More cars, fewer people, fewer businesses, and a shrunken impoverished neighborhood.

ODOT’s proposal to spend as much as $1.45 billion is supposed to revitalize the neighborhood. But flaw in the proposed freeway widening is that it makes both these problems–the freeway and local car traffic–worse. It widens the freeway–pushing it even closer to other uses like the Harriet Tubman Middle School, and funnels even more cars not just on the freeway but on local streets, like Vancouver, Williams, Broadway and Weidler. Plus ODOT would cut back the corners of major intersections to enable cars to drive even faster on these streets, and would its relocated freeway ramps would add more than a million miles of car travel to local streets.

Capping a small segment of the freeway does not create a neighborhood

We’re told that “caps”—actually just slightly wider freeway overpasses—will somehow magically heal the neighborhood. But again, the problem is not just with one or two blocks, but about giving over the whole neighborhood to transient uses (like the Moda Center and Convention Center) and the demolition of housing and neighborhood sized streets. The construction of I-5, combined with the Memorial Coliseum, obliterated the dense street grid that underpinned Albina.

Creating a few blocks of buildable land, sitting directly over the noise and pollution of the widened I-5 freeway, and surrounded by fast-moving traffic on arterials and freeway-on-ramps is a pedestrian hostile environment that no one will want to linger and a place where no business will thrive. The one example that freeway advocates point to, a cap over I-80 in Reno, houses a Walgreens drugstore and its parking lot; a transient, car-oriented use, not the hub of a revitalized neighborhood.

A freeway cap is no place for parks, sidewalk cafes, restaurants or grocery stores. Its just another desolate off-ramp, designed for the needs of outsiders and travelers, not local residents. The proposed highway cap would be bisected by the northbound freeway on-ramp to I-5, as well as four major arterials carrying traffic to and from the freeway (Vancouver, Williams, Broadway and and Weidler). The project’s caps can only hold 3- to 5- story “lightweight” buildings, and OregonDOT is providing no funding to build anything on the site. It doesn’t even know what it will put atop its bare concrete covers. This is only a restorative space if you’re a highway engineer.

A neighborhood for the people who live there, or people driving through?

In cities across the country, freeways and the car-dependent development patterns and urban depopulation they’ve engendered have divided and decimated historically Black urban neighborhoods. As the Los Angeles Times editorialized: the real monuments to institutional racism are the nation’s urban freeways.

Freeways, and the high speed on-ramps and arterials that feed them privilege people in cars driving through a neighborhood over the people on foot, biking, breathing and just living in the neighborhood. ODOT’s proposed I-5 freeway widening privileges the interests of peak hour car commuters from Clark County (75 percent white and with average incomes of $82,500) over the kids who attend Tubman School (two-thirds kids of color; half on free and reduced price lunches), and others who live in the neighborhood (where fewer than half of workers drive alone to work: most walk, bike or take transit, according to census data).

If we want to want to make amends to those whose neighborhood was devastated by the I-5 freeway and its car-dependent development pattern, the last thing we want to do is widen the freeway that caused this problem. And freeway covers, no matter how elaborate or expensive won’t replace the housing lost or the damage done to the fabric of the entire Lower Albina area.