Wide variations in regional home price patterns tell us a lot about housing markets and cities

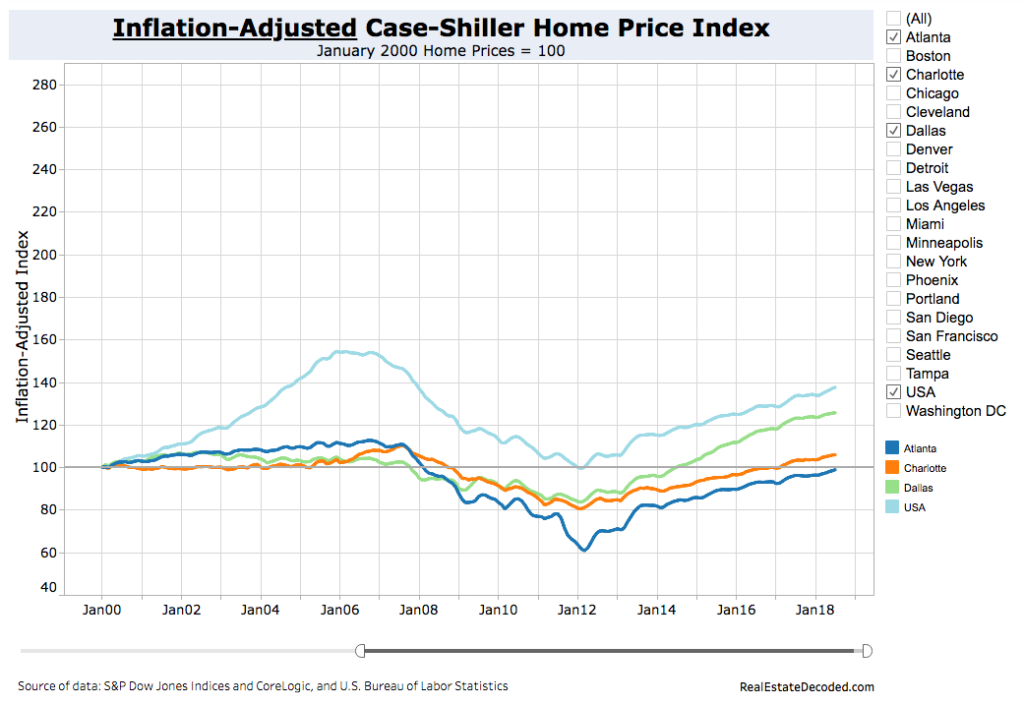

Yesterday, we looked at the path of inflation-adjusted home prices in the US. While much attention has been paid to the fact that nominal prices of homes have, in many markets caught up to or surpassed levels recorded in the peak of the last decade, an apples-to-apples comparison that corrects housing prices for inflation shows that in most of the nation, home prices are still lower now than at the peak. But that’s just the national average. A more nuanced picture appears if we look, as we should, market-by-market across the nation.

Today, we trace out the different patterns of real home prices in different cities across the country. While as a whole, real, inflation-adjusted home prices are below the level of the 2006 peak, there’s been substantial variation across markets.

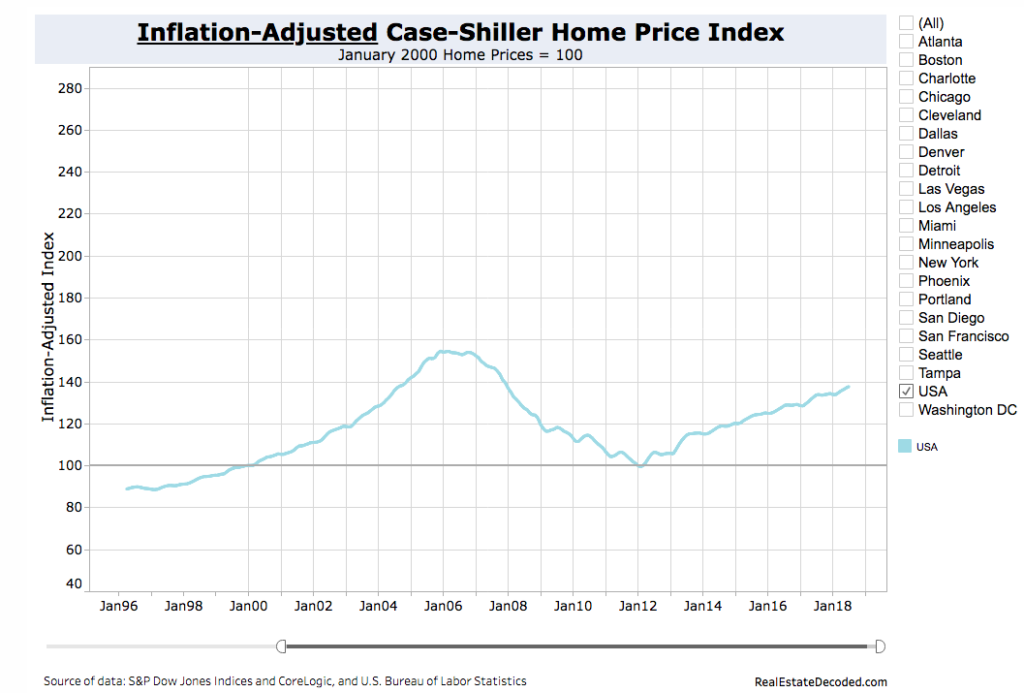

Our data source today is the Case-Shiller home price index, which is calculated for major markets nationally on a monthly basis. We’re using the inflation-adjusted levels of the index, keyed to their year 2000 values, as reported by the real estate website Real Estate Decoded.com. Values above 100 represent an increase in real home prices since 2000; values below 100 represent an inflation-adjusted decline.

First, let’s take a look at the national picture. The housing bubble is very much in evidence from 2004 to 2006, as is the housing market collapse (with declining real values through early 2012. Nationally, housing prices grew 54 percent from 2000 through early 2006 (to an index value of 154), and gave up all of those gains by the early part of 2012 (index value 99). Since then, real home prices have recovered to an index value of 138–about equal in inflation-adjusted terms to where they were in early 2004.

The experience of most cities falls into four categories.

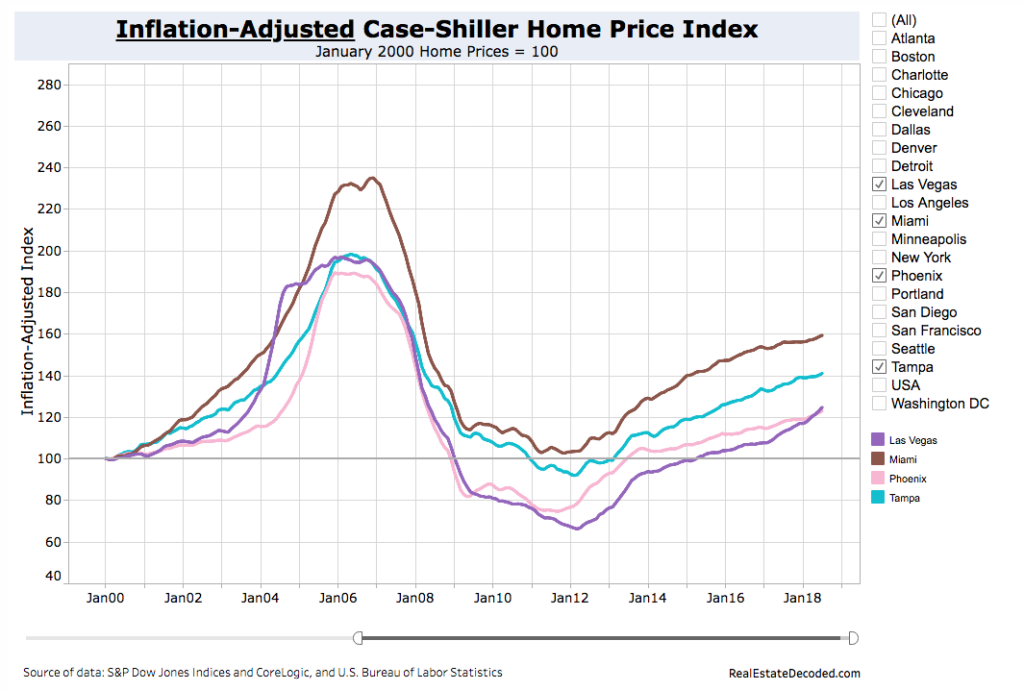

Boom and Bust Markets

The most volatile housing markets have been in Florida, Arizona and Nevada. These places were the epicenter of the housing bubble, where loose mortgage lending fueled a building boom, and where the collapse was most dramatic. Phoenix, Las Vegas, Tampa and Miami all show an even more pronounced surge and even steeper decline than the nation as a whole. They also have home values today that are still well below the inflation-adjusted peak. Miami is still about 70 points lower on the index than at its peak; Phoenix and Las Vegas values are only about 20 percent higher than in the year 2000, after spending more than five years in sub-2000 values territory.

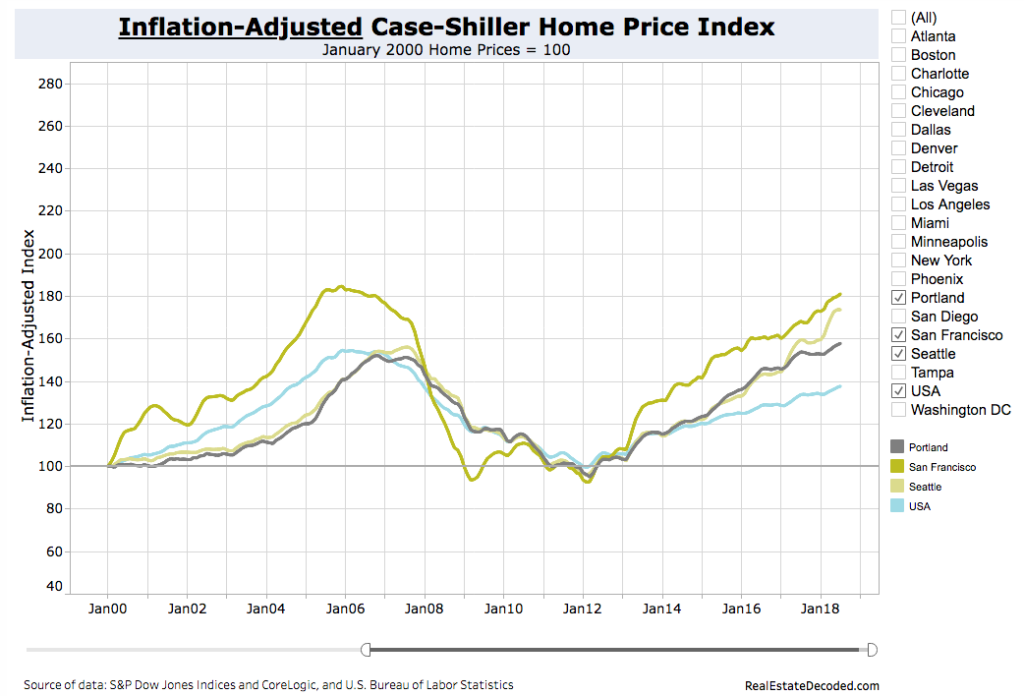

Constrained Markets

In several fast growing, tech centered metro areas, housing prices have risen rapidly in the past few years. In places where it’s been difficult to built more housing, economic growth has translated into rapidly growing home prices. This tendency is apparent especially in San Francisco and Seattle, and to a somewhat lesser extent in Portland. Each of these markets bottomed out in real terms in 2012, and the appreciation since then has taken each of them back (or very nearly back) to their mid-2000’s peaks.

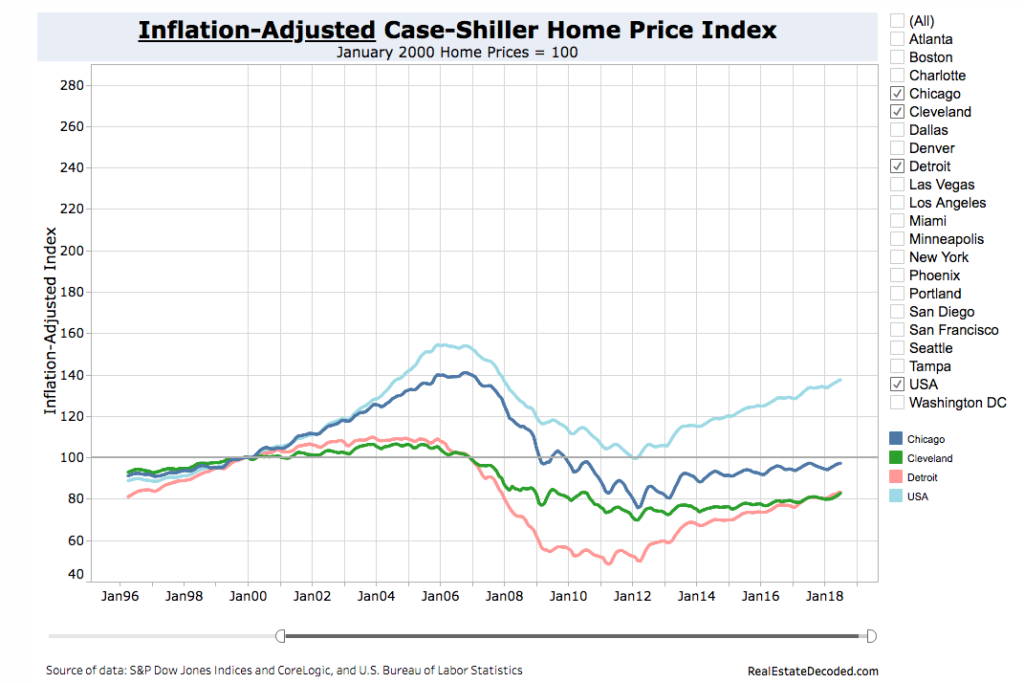

Lagging Markets

In some metropolitan areas with slower growing economies, home price gains have been much more muted. If we look at three Midwest metros–Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit–its apparent that real home prices haven’t recovered even to pre-2000 levels, much less their bubble era peaks. In all three metro areas, the inflation-adjusted price of a home today is less than it was two decades ago. This means that housing has not been much of source of real wealth accumulation for long term buyers, and for those who bought during the bubble years, the real value of their investments has been negative, in inflation-adjusted terms. While there’s not a lot of good news here, Detroit’s housing market has recovered somewhat in the past five years: it was down to just over half of its year 2000 value in 1980, and is now at about 80 percent of year 2000 value.

Elastic Markets

Our final set of local markets include the Sunbelt cities where its relatively easy to build new housing in abundance. Interestingly, these places largely avoided most of the wild gyrations of the housing bubble. Prices neither rose nearly as much in the bubble years, nor did they fall as dramatically (again, in inflation-adjusted terms) in the years of the Great Recession. These cities include Charlotte, Dallas and Atlanta. all of which have very muted price swings. The price of a home in Atlanta or Charlotte is roughly the same, adjusted for inflation, that it was in 2000. Dallas homes have appreciated in the past few years, but over the two decades shown here, have are still gained less than the typical US home.

To paraphrase former House Speaker Tip O’Neill, all housing markets are local. The health of the local economy, its amenities and desirability as a place to live, and whether land use and development regulations make it easy to add more housing all have a bearing on the trajectory of housing prices.

The experience of the last two decades shows that a housing boom, bubble, and bust were felt quite differently in different metropolitan areas depending on these factors. While a few places have recorded real increases in housing prices that bring home values back near to their housing bubble peaks, far more markets remain at inflation-adjusted price levels well below the peak, and as we’ve shown, in many markets, home prices are no greater today, adjusted for inflation than they were in the year 2000.