What City Observatory this week

1. How ODOT destroyed Albina. Urban freeways have been lethal to neighborhoods, especially neighborhoods of color, in cities throughout the nation. While the construction of Interstate freeways gets much of the attention (as it should), the weaponization of highway construction in minority neighborhoods actually predates the Interstate system. In Portland, in 1951, the state highway department built a mile long extension of US Highway 99W along the Willamette River which cut the predominantly black neighborhood off from the waterfront.

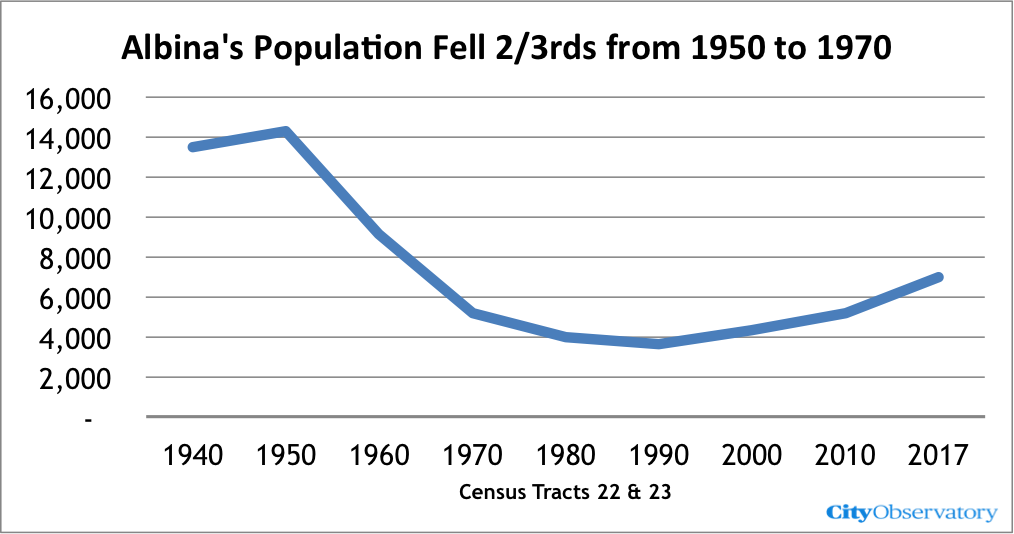

That was the first of a series of road projects, culminating in I-5 and the Fremont I-405 Bridge which wiped out much of the neighborhoods housing, and propelled the neighborhood’s decline. Albina’s population fell by nearly two-thirds from 1950 to 1970.

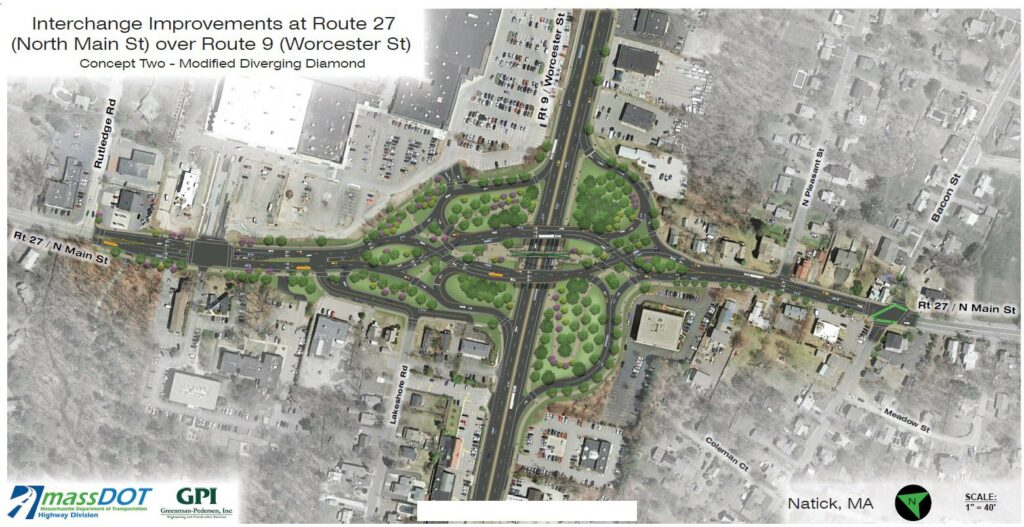

2. Highway greenwashing: Natick’s diverging diamond: Highway departments know that their traditional asphalt everywhere solutions play poorly with a public more attuned to climate change and quality of life. So nowadays, they dress up highway expansion projects with an artistically crafted veneer of green and pedestrian friendly images. The latest example of this comes from Natick, MA, just outside Boston, where MassDOT is looking to turn an existing 1950s era highway interchange into a much larger “diverging diamond.”

Must read

1. Five against I-45. Paris has Mayor Anne Hidalgo, Houston has County Judge Lina Hidalgo. Both are forceful and articulate advocates of re-thinking urban transportation to create fairer, safer, healthier and more successful cities. In a concise must-watch eight minute video, Judge Hidalgo makes a definitive five point case against TXDOT’s plan to spend billions to widen I-45 through the middle of Houston. It’s bad for road safety, for air quality and health, would displace hundreds and wouldn’t solve the highway’s chronic congestion problem. Instead, she argues, the city ought to be investing in alternatives like bus rapid transit, narrowing the footprint of the project, and prioritizing people over futile attempts to make cars move faster.

If you want a picture of what urban leaders can do in the face of truly retrograde highway widening efforts, just watch this video . . . and share it with friends.

2. Embracing Reduced Demand. City Observatory readers will be very familiar with the concept of induced demand, the idea that building more highway capacity tends to generate additional traffic, quickly erasing any congestion reduction benefits from wider roads. But the reverse is also true: reducing road capacity generally causes traffic to disappear. The phenomenon of “reduced demand,” says CNU’s Robert Steuteville, should be an important precept for transportation planning. Too often, highway agencies push back against projects to calm traffic, reduce speeds and accomodate bikes and pedestrians, arguing that reduced road capacity will produce congestion or gridlock. But as Steuteville points out, time after time, cities have made major reductions in road capacity, often by tearing out entire freeways, and rather than traffic getting worse, it largely evaporates. The trouble with some current freeway removal projects, for example in Syracuse and Buffalo, is that if anything, engineers are still too timid in applying this fundamental lesson. The boulevards designed to replace freeways are often over-sized, out of an irrational fear of gridlock. He concludes:

You really don’t believe in induced demand, if you don’t also believe in reduced demand. Traffic engineering/planning is going on a hundred years as a profession. It’s time to learn from history, to believe the science, to get smart about street design, to fully use the idea of reduced demand where it has the potential to improve a city’s economy, society, and mobility.

3. A solution for the diverging diamond blues. Jeff Speck, author of Walkable Cities, also weighed in on Natick’s proposed diverging diamond interchange. His critique strikes a frustrated, plaintive tone, asking a series of devastating questions, including:

How can we create a park that nobody will use, and then give it unhealthy air quality? How do we ensure that this large, valuable parcel never produces revenue? How do we communicate to aliens our plans to abandon earth?

Speck also offered a better solution, one that backs away from expanding the highway, slows traffic, and makes the area at least somewhat better for pedestrians. Based on some successful examples in Indiana, he proposes that MassDOT consider a kind of elongated traffic circle, a peanut interchange, that naturally slows highway traffic and accommodates multiple turning movements (without consuming a vast land area and creating a disorienting experience for pedestrians).

New Knowledge

Less is more: How reducing vehicle miles traveled improves the economy. For decades, there’s been a naive assumption that more movement (meaning more driving) somehow makes us richer. Turns out that was probably never true, and today, the places that are built in a way that enables people to drive less are more economically successful. That’s the conclusion of a research review conducted by USC transportation professor Marlon Boarnet and his colleagues. This research emphasizes a theme we’ve long advocated at City Observatory: urban form that reduces vehicle miles traveled (VMT) saves consumers money that they can spend to make their lives better. That reallocated spending can produce measurable local economic gains.

The research is conveniently summarized in a new 2-page non-technical publication, “Urban Design that Reduces Vehicle Miles Traveled Can Create Economic Benefits.” This policy brief summarizes studies that look at the economic impacts of low-traffic neighborhoods. It finds, neighborhood businesses can benefit from walkability, in some cases, street closures or traffic lane reductions are associated with improved neighborhood business activity, and that house prices are higher in places with VMT-reducing urban design.

Boarnet, M.G., Burinskiy, E., Deadrick, L., Gullen, D., Ryu, N. (2017). The Economic Benefits of Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT)- Reducing Placemaking: Synthesizing a New View. UC Davis: National Center for Sustainable Transportation. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5gx55278