What City Observatory this week

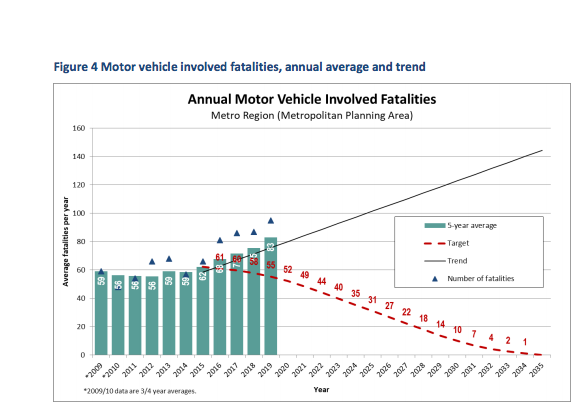

1. The failure of Vision Zero. Like many regions, the Portland metropolitan area has embraced the idea of Vision Zero; a strategy of planning to take concrete steps over time to reduce the number of deaths and serious injuries from road crashes to zero. A key step in Vision Zero is setting—and monitoring—well-defined targets for steady progress over time. Metro, Portland’s regional planning agency has just produced a report card for the region’s efforts through 2019; and its pretty clear that the result is all “F’s”: Of 25 Vision Zero indicators, the region is on track to achieve exactly none of them. Rather than decreasing, as called for the in Vision Zero plan, roadway deaths are increasing sharply.

As the region’s safety planners have known for some time, roadway deaths are highly concentrated on the region’s multi-lane arterial highways. But rather than fix these, the state highway department, ODOT, is devoting billions to widening major freeways (which are among the region’s safest roads already). In addition, lower gas prices since 2014 have spurred more driving, more crashes and more deaths. Vision Zero is a noble target, but it’s apparent in the Portland region, that the current plan is failing in every respect.

2. Portland’s apartment market has its “Wile E. Coyote” Moment. Ever since the implementation of one of the nation’s toughest inclusionary zoning requirements in early 2017, Portland’s apartment market has been like Warner Brothers “Wile E. Coyote”: motoring on rapidly through clear air with no visible means of support. Apartment starts and completions—propelled by a land rush of applications filed to beat the inclusionary zoning requirements—have produced increased apartment supplies, rising vacancies, and lower rents. But finally, the coyote has looked down: Apartment completions have fallen by roughly two-thirds in the past year, and there’s very little in the pipeline now.

There’s clear evidence developers are put off by the inclusionary zoning requirement: there’s been a surge in 20 unit (and smaller) apartment buildings (exempt from the IZ requirement): meanwhile no new apartments in the 21-25 unit range have been completed in the past year. As we warned two years ago, the temporary incentives created by the IZ’s “grandfathering” provisions provided a temporary respite for the housing market, and now the negative impacts on the inclusionary requirements are crushing the development of new apartments. The negative effects on housing supply will be felt for many years, and will cast a long shadow over housing affordability in Portland.

Must read

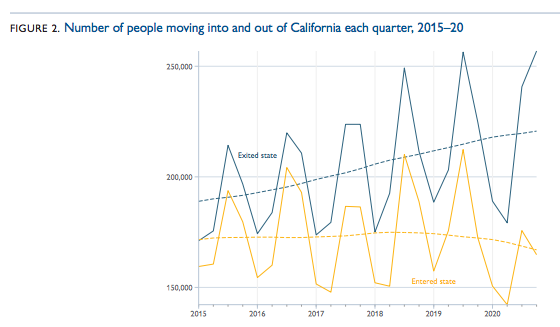

1. Are people leaving California? Natalie Holmes of the Policy Lab at the University of California offers an analysis of credit bureau change of address data to assess migration in and out of the Golden State. They find that while there has been a sharp increase in net movement out of the City of San Francisco, there’s no evidence of an exodus from California as a whole. Most of those leaving San FRancisco are moving to other locations in the Bay Area, and to a lesser extent elsewhere in the state, rather than other states. As Holmes notes:

San Francisco has seen a 31% increase in departures and 21% decrease in entrances since the end of March 2020. Net exits from San Francisco increased 649%, from 5,200 to 38,800.

The credit report data for the past five years show a gradual and continuing increase in the number of out-migrants (blue line) and a flat-lining, and recent slight decline in in-migrants (yellow line). The data show a strong seasonal pattern to movement activity. Its also important to note that credit report data likely undercount certain groups (international immigrants and young adults, who may not have established credit records; in states like California, this likely significantly undercounts in-migrants).

2. A close look at the limits of NIMBYism. Toronto’s Globe and Mail architecture critic Alex Bozikovic has a compelling essay on the origins of, and problems emanating from North American NIMBYism (Not in My Backyard). In Canada, as in the US, land use decisions are heavily biased toward protecting the status quo, especially in the form of giving single family zoned neighborhoods effective veto power over new development. The inevitable result has been rising home prices, declining affordability, and intensified economic (and racial/ethnic) segregation. The solution according to Bozikovic is to allow much more density and variety of housing in cities, with an explicit objective of growing upward and inward, rather than ever outward. In rousing few closing paragraphs, he writes:

What good is accomplished by locking down so much of our cities to change – so that you must be affluent to live there? Where would be the harm in allowing more big things next to small things, more houses giving way to apartment buildings? People of different generations, income levels and interests living together? . . . More social housing would be crucial. Progressives in the world of housing policy are often skeptical of such a bargain. But our current regime does little for the less privileged; it builds segregation and inequality, and encourages middle-class people to settle in car-oriented suburbs. . . . The policy objective should be simple: All new growth should happen in places that are already built out. No more building on greenfields. No more sprawl.

3. Making Houston safer for pedestrians. A couple of months back, we took Houston to task for what we called “performative pedestrian infrastructure.” The Houston-based Kinder Institute’s Andy Olin wrote a thoughtful reply to our analysis. In the spirit of constructive dialog that its offered, we urge City Observatory readers to consider this article. Olin’s key point is that as auto-dominated as Houston is (and most other US cities are), you have to start somewhere.

New Knowledge

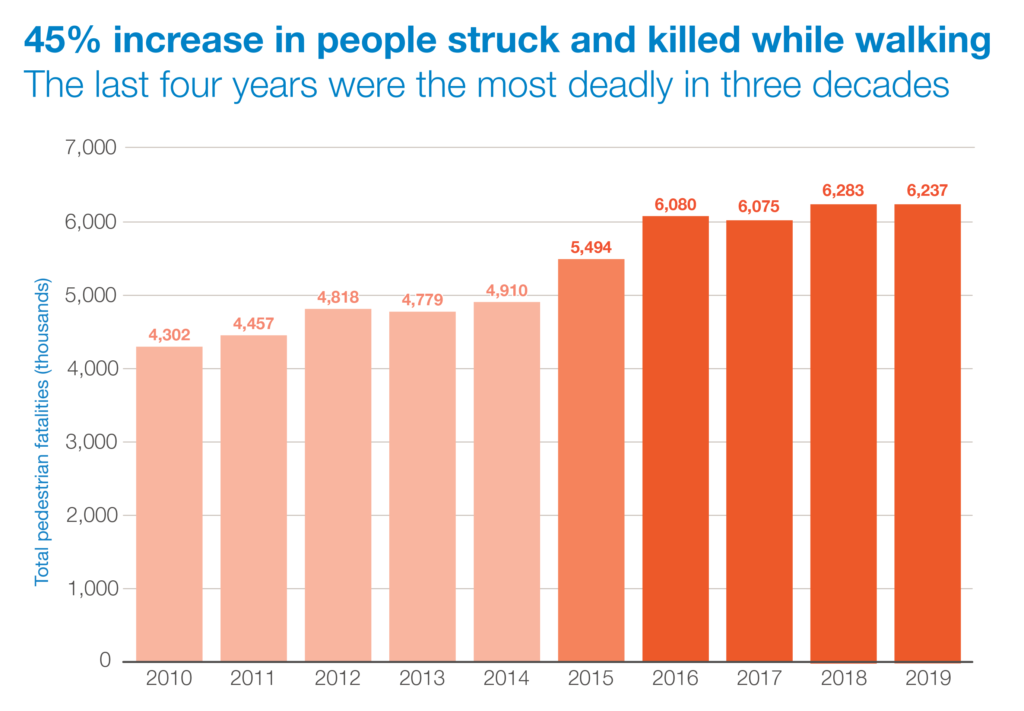

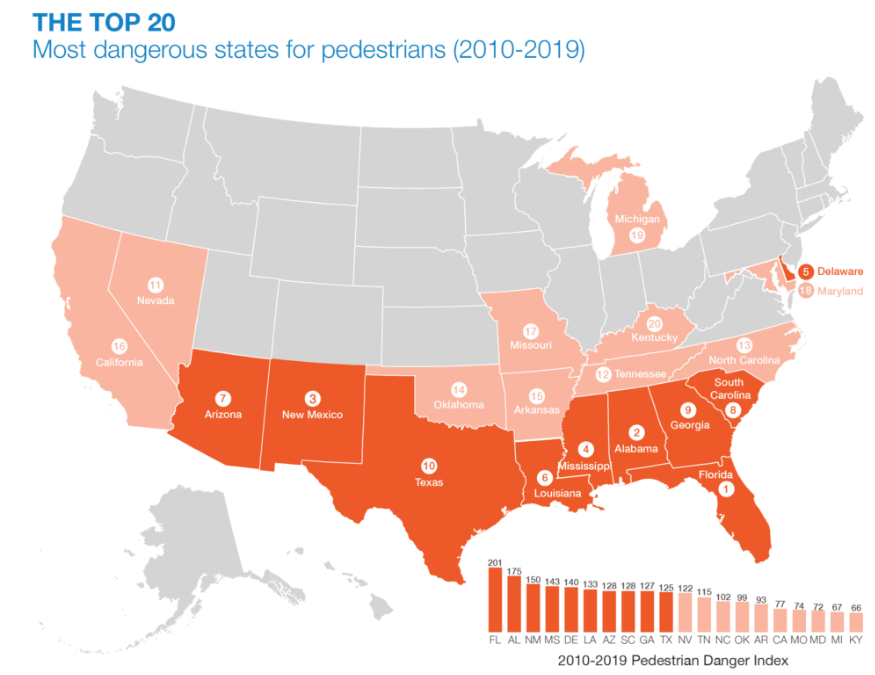

Even more dangerous by design. For the past several years, Smart Growth America has been highlighting the safety flaws literally engineered into our current road system: the way we build roads in the US inherently puts people, especially vulnerable road users on foot and on bikes, in harm’s way. Far from being accidents, the huge and continuing volume of crashes is a reflection of the conscious design choices we’ve made. Dangerous by Design, 2021 shows that xxxxx

The report illustrates that our streets are disproportionately deadly for people of color and older Americans. Hispanic, Black and elderly persons are much more likely to suffer death or serious injury as pedestrians. There’s also a distinctive geographic pattern to pedestrian death rates; Sunbelt states from Arizona to Florida consistently have the highest rates of pedestrian fatalities.

The growing number of pedestrian deaths is symptomatic of the structural biases in road design: Engineers routinely prioritize vehicle speed and throughput over making streets safe places to bike and walk. Wide, multi-lane arterial roads, with sweeping corners and slip lanes encourage high speeds regardless of posted limits and create inherent danger for pedestrians. Smart Growth America argues for “complete streets” policies that prioritize the safety of vulnerable users over higher vehicle speeds: until we adopt such policies, it’s likely the pedestrian death toll will continue to rise.

Smart Growth America, Dangerous by Design, 2021.

In the News

Strong Towns re-published our essay, “The Fundamental, Global Law of Road Congestion,” detailing international studies that show that additional freeway capacity simply generates a proportionate increase in traffic, meaning road widening is an inherently futile tactic for reducing congestion.

Alan Ehrenhalt, of Governing, gave City Observatory a shout out in his column: “Where Americans are moving, and why they are really doing it.” His conclusion: despite what you may have read, there’s no urban exodus and young adults aren’t decamping from Brooklyn to Mayberry.