What City Observatory did this week

1. Miami’s double standard for charging road users. The City of Miami is hoping to make their streets a safer place for bikes and scooters by building protected lanes along three miles of the city’s downtown. The city plans to pay for this infrastructure by taxing each registered scooter daily. This fee got us thinking – how does the price we charge scooters compare to the price that we charge cars? What we found: e-scooters are paying four to 50 times as much to use the public roads as cars. Automobiles take up the most space, create unsafe environments for other users, and damage the roads. Scooters help reduce congestion, fit on a sidewalk, and provide environmentally friendly ways to travel through a city. Yet, scooters pay significantly more to use the road. If we want greener, safer, and more efficient transportation systems, we ought to reconsider how we charge its users.

2. It works for bags, bottles and cans, why not try it for carbon? A newly enacted law in Denver requires grocery stores to charge customers a dime for each grocery bag they take. Echoing similar bag fees in other places, this provides a gentle economic nudge to more ecologically sustainable behavior. And the evidence is that it works–it London, single use bags are down 90 percent. We ought to be applying the same straightforward logic to carbon pollution, and ironically, the bag fee, on a weight basis is 20 times higher than the charge most experts recommend for carbon pricing.

Must read

1. Giving up on the “user pays” principal for cars and driving. The nation is in need for roads, bridges, and transit infrastructure. Gasoline taxes, a “user pay” system, have long been a method that the United States has funded these needs, but the tax level has been untouchable for nearly 30 years. As a result of inflation and increasingly fuel-efficient cars, the Highway Trust Fund has struggled to get the same impact from the gas tax. The House’s new surface transportation bill has no mention of this gas tax. Instead, the Highway Trust Fund is receiving cash from deficit financing. The bill is financed by a one-time $148 billion transfer from the U.S. Treasury to Highway Trust Fund. What this amounts to is a massive subsidy to more driving, more pollution and more greenhouse gas emissions. If we really had a “user pays” system, as with a carbon tax or a congestion fee, we’d have a lot less traffic and congestion.

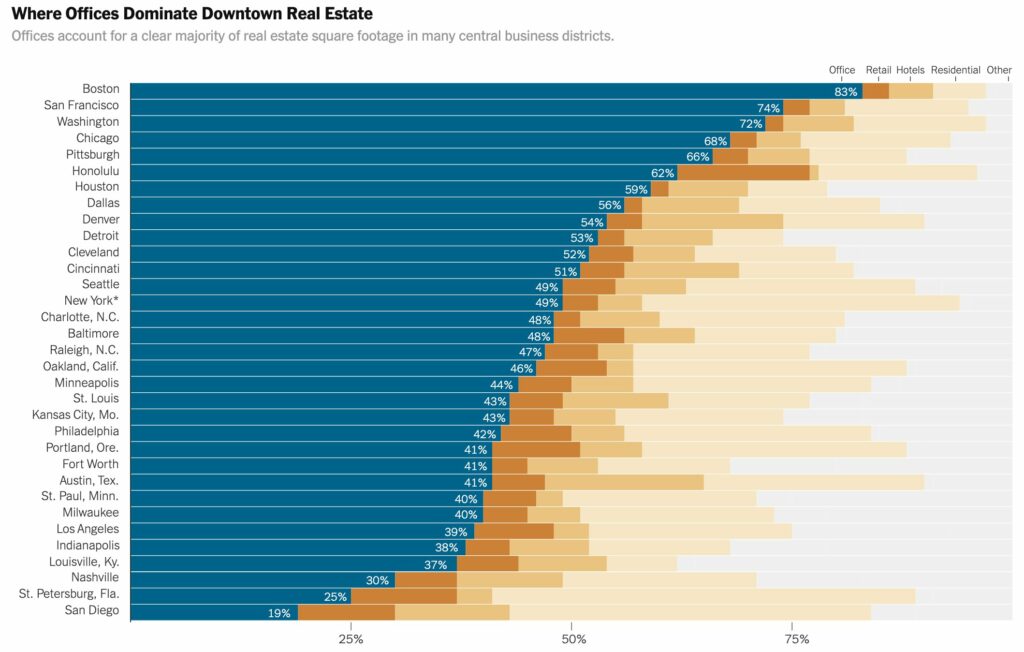

2. Which downtown’s are most dependent on a return to the office? Downtowns are much like investment portfolios – the more diverse, the more resilient they will be. The New York Times’ Emily Badger and Quoctrung Bui examine the state of downtown business districts across the nation. According to their analysis, some cities have downtown business districts with office space taking up 70-80 percent of all real estate. These office dominated cities are susceptible to shocks, recessions, and especially global pandemics. Kourtney Garnett, the head of Downtown Dallas, Inc., offers a solution to strengthen these city centers: “Build more residences, diversify the economy, give people reasons to linger past 5 pm.” There’s a surprisingly large variation across metro areas in terms of the amount of downtown space devoted to offices, retail, hotels, residential and other uses, as this NYT chart illustrates.

3. Let’s build mixed income housing in high income, high amenity, high opportunity neighborhoods. The United States housing supply shortage is a dire issue that continues to grow. The struggle to find affordable housing with desired amenities has pushed middle-income households further and further from city centers, increasing sprawl and commute times. Suburban growth also tends to fuel auto-dependence and increase total vehicle miles of travel by households, key contributors to climate change.. The need for housing supply and the climate impact of increased transportation present two huge problems. In this article, Zack Subin suggests a combined solution to both problems. He writes that, “we must reduce vehicle miles traveled by investing in inclusive, complete, compact, transit-oriented communities.” Subin explores the potential opportunity for mixed-income housing to create low-carbon-footprint neighborhoods and increase the housing supply. If we create housing in the right neighborhoods, we could see significant positive impacts in the nation’s pollution emissions and housing supply. Climate advocates, come join the housing movement so we can meet our pollution and equity goals together.

New Knowledge

The food landscape of rural America. There’s been a lot of concern raised about food access in urban areas, in particular the idea that food deserts contribute to poor nutrition (the evidence for this is weak). There’s little dispute however, that physical access to food stores is lowest in the nation’s rural counties, where there are few stores and people routinely have to travel great distances. A new report from the USDA reports on the changes in the rural food retailing landscape.

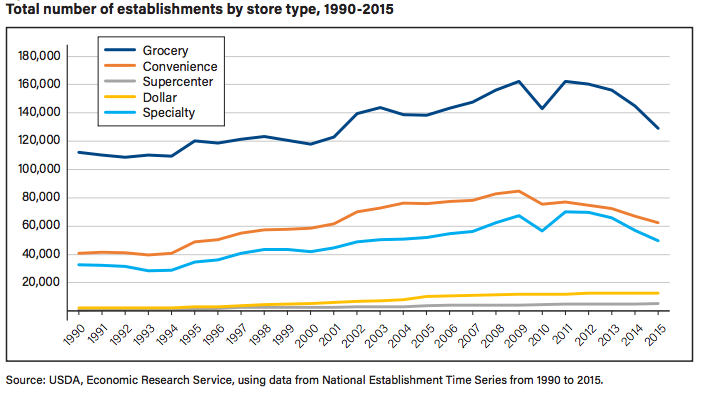

The report looks at trends over the 25 year period from 1990 through 2015. Through most of that time the total number of food retailers in the US was increasing, but since the Great Recession, the most common types of food retailers—grocery stores, convenience stores and supercenters—have declined in number. In contrast, the number of Dollar stores has increased.

The report focuses on the trends in the nation’s non-metropolitan counties. Overall, most of the food retailers in these counties are single-establishment firms (think small, often-family owned traditional grocery stores). While more numerous than other types, these stores are much smaller (grossing about $800,000 per year, compared to $4-10 million per year for a chain supermarket), and their numbers are dwindling. Weak economies in rural areas, and competition from national chains, and more recently Dollar stores, is cutting into the financial viability of these businesses.

The net effect of these changes was to reduce food availability and choice in many non-metro areas:

Among urban nonmetro counties, the percentage of counties with fewer than 8 food retailers per 10,000 people increased from 21 percent to 33 percent. The number of food retailers per capita decreased by 16 percent for these counties. Among rural nonmetro counties, the percentage of counties with fewer than 8 food retailers per 10,000 people increased from 11 percent to 27 percent. The number of food retailers per capita decreased by 19 percent for these counties. The percentage of rural nonmetro counties with no food retailers increased from 1 percent to 3 percent.

Overall, the median number of grocery stores per capita in non-metro areas decreased about 40 percent since 1990, that means that rural residents are even further from food, on average, than they were 25 years ago.

Stevens, Alexander, Clare Cho, Metin Çakır, Xiangwen Kong, and Michael Boland June 2021. The Food Retail Landscape Across Rural America, EIB-223, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=101355