What City Observatory did this week

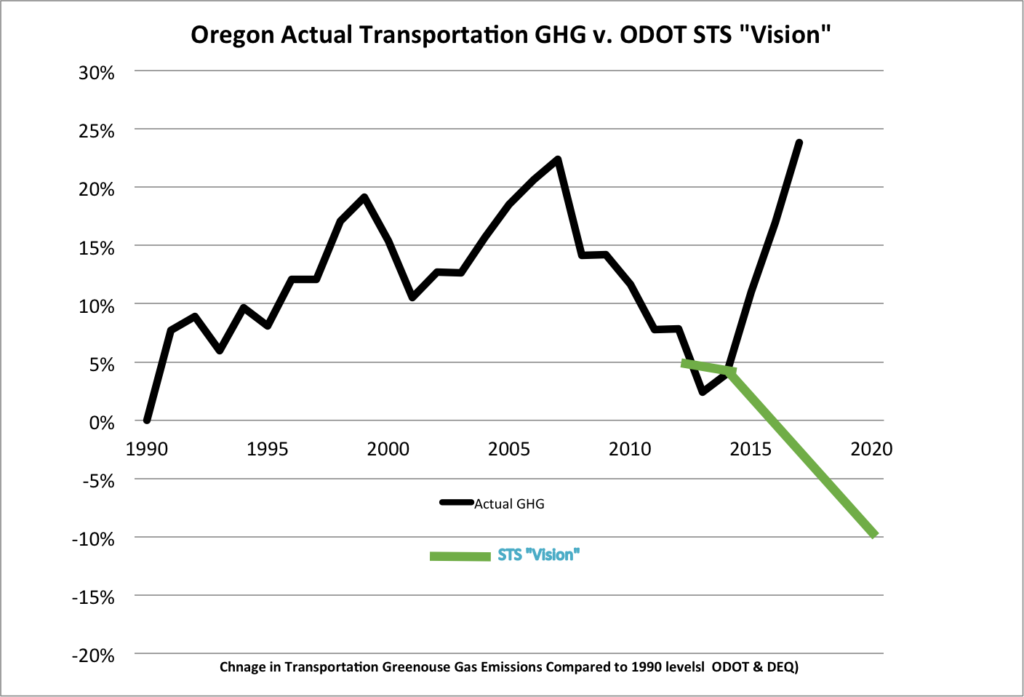

Selling Oregon into highway bondage. Oregon is moving ahead with plans to issue hundreds of millions—and ultimately billions of dollars of debt to widen Portland-area freeways. And it will send the bill to future generations, and perversely, commit the state to ever increasing levels of traffic in order to satisfy bond-holders. Just the right strategy for dealing with a manifest climate crisis, right?

The single largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the state is transportation, and those emissions are growing, up 1,000 pounds per person in the Portland metro area in the past five years.

And the Oregon Department of Transportation’s plan for responding: building even more highways in the Portland metro area; and not only that, going deeply into debt to pay for those highways—burdening future generations with both the financial and environmental costs of more driving. In theory, the bonds will be repaid by tolls, but the agency has no history of forecasting toll revenue, and routinely overspends its budgets on megaprojects. And tolling essentially commits the state to increasing traffic levels in order to pay back bondholders. It’s the height of intergenerational climate warfare, and its packaged as business as usual, technocratic trivia.

Must read

1. Returning to the office: Young workers value in-person work. There’s a lot of glib prognostication that the advent of zoom will lead to remote work displacing office work, and undercutting city economies. But the assumption that everyone does well working remotely misses the fact that in-person workplace interactions are more powerful and important for some functions (team-building, socialization, feedback) and some workers (especially younger ones). While seasoned veterans can take their accumulated knowledge and networks and work remotely, young workers are still learning and forming complex ties and forging an identity. As Erica Pandley at Axios:

Transitioning to remote work is far easier for veteran employees who have already developed social capital in the workplace and know how a company operates. Freshly minted members of the workforce stand to miss out on those valuable skills and opportunities if they can’t come back to the office. . . . A whopping 40% of college students and recent graduates prefer fully in-person work, according to a new poll by Generation Lab.

The survey says three quarters of young workers feel they miss out of office community by working remotely, and two in five would lose out on mentoring. Two-thirds of young workers say they want in-person feedback from their managers, rather than receiving a written report or chatting over Zoom. This kind of face-to-face interaction is what has propelled the growth of city economies, and been especially important to young people, for decades. We shouldn’t expect it to disappear now.

2. Would Texas be better off spending $25 billion on something other than more highways? Texas has recently begun to move ahead on plans to expand highway I-35 through downtown Austin. The stated goal is to provide more efficient and safer travel for the hundreds of thousands of drivers who use the highway everyday. Although, as we’ve explored numerous times at City Observatory, increasing the number of lanes does not lead to more efficient travel. So, what if the state of Texas did not expand their highways? Megan Kimble at the Texas Observer takes it a step farther. She ponders:

“What if, instead of building our aging roads back wider and higher—doubling down on the displacement that began in the 1950s and the climate consequences unfolding now—we removed those highways altogether? What if we restored the scarred, paved-over land they inhabit and gave it back to the communities it was taken from?”

Kimble writes a thoughtful and informative piece on the state of Texas highways and the possibility for transcendent change. She interviews planners and activists within the state, exploring what the potential for the highway land could be. This “What if” question is not just imagination. It is an idea for real, substantial change. Expanding the roadway will only bring more congestion. Taking it away could create more equitable and sustainable communities for all, particularly those harshly impacted by the highway’s construction.

New Knowledge??

Our “New Knowledge” feature this week has question marks appended because, as we’ll explain, we’re not at all sure this particular article gets things right. But because it purports to shed light on the very salient question of how upzoning city neighborhoods affects population change, we think it’s worth a closer look, and some skepticism.

Columbia University’s Jenna Davis has published a journal article, and a web commentary summarizing this work. The paper looks at the demographic change in New York City census tracts between 2000 and 2010, and reports finding a correlation between city initiated zone changes and an increased probability that the share of non-HIspanic white population increases. Tracts that had city upzoning were about 25 percent more likely to experience an increase in white population share than tracts that weren’t upzoned. It’s pretty clear that many will read this study as somehow proving tha upzoning makes neighborhoods whiter. Davis says her findings imply that “upzonings might accelerate, rather than temper, gentrification pressures.”

We think there are several problems with drawing this conclusion. They include timing, threshold effects, other demographic factors, causation, and a poorly described dependent variable.

The dependent variable in this analysis is an increased share of non-Hispanic white population. The paper doesn’t say how many Census Tracts experienced an increased share of white population in New York between 2000 and 2010. Demographic change in most neighborhoods is slow and small; relatively few neighborhoods totally change their demographic composition. To put this in perspective, over the 40 years between 1970 and 2010, just 10 of 443 majority Black census tracts in the New York metro area transitioned to majority white composition (about 2 percent). (Data from the Brown University Longitudinal Tract Database).

The fact that there’s a correlation between upzoning and the probability of a white share increase doesn’t say anything about the direction of causality: It is possible, even probable, that the city chose neighborhoods to upzone where the white population share was increasing. The study also doesn’t apparently have any minimum threshold for the increase in the white share of the population: even a 0.1 percent increase in share might qualify. Also, it’s worth noting that even if the share of the white population increases, that doesn’t necessarily imply that the number of non-white residents of a neighborhood decreases; new housing units could allow both more white and more non-white residents in a neighborhood, even if the shares of the two groups change.

That possibility is heightened by the timing of upzones. According to the paper, the average upzone occurred just 18 months before the 2010 Census. That’s not enough time to actually build additional housing, and this suggests that the demographic change, if any, occurred mostly before the upzoning. Notice that the paper doesn’t look to see whether, or how many additional housing units were built; it’s implicitly arguing that the rezoning itself, even without construction, caused the observed demographic change.

It’s also worth noting that other variables included in the estimation had a much bigger impact on neighborhood change. In particular, there was a strong correlation between an increased share of the white population and the share of the neighborhood that was either married or had children. One key component of population change is births, and if a particular neighborhood had a disproportionate share of of White residents in their child-bearing years relative to neighborhood’s overall population, you would expect the demographic composition of the neighborhood to shift based on births of white children—a factor unrelated to zoning.

Jenna Davis, “How do upzonings impact neighborhood demographic change? Examining

the link between land use policy and gentrification in New York City.” Land Use Policy 103 (2021).

Jenna Davis, “Double edged sword of upzoning?” Brookings.edu.