It’s hard to think of an issue that is more quintessentially local than zoning. It’s all about what happens on the ground on a specific piece of property in a particular neighborhood. It’s the bread and butter of local governments and neighborhood groups. Zoning and land use seem about as far removed from national economic policy as just about any issue you can imagine.

Or so you might have thought until last week.

On November 20, Jason Furman, Chair of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers delivered a speech at the Urban Institute that is required reading for all city leaders. In it, he spells out why zoning—and by extension, how we build cities—matters vitally to tackling national problems ranging from accelerating economic growth to broadening opportunity to reducing inequality. The Furman speech has already drawn media attention: Matt Yglesias, who’s been on the zoning beat for a while, wrote in Vox that Furman’s speech demonstrated that “regulations mandat[ing] single-family homes” are “a disaster” for “younger people, for renters, and for the overall cause of social and geographic mobility.”

The Atlantic, in its story, emphasized that Furman “isn’t alone in his belief that the growing prevalence of economic rents are one of the root causes of inequality today.” It also related some of the history about how zoning became such a powerful force in metropolitan economies—much of which overlaps with what we published here last week.

This is a big deal. For the most part, macro-economists don’t much concern themselves with cities. Sure, they’ll focus in on housing starts—because housing construction and finance are so closely related to the economic cycle and so sensitive to changes in monetary policy. But most of urban economics is generally treated by these national economic modelers as a quiet backwater of applied microeconomics. So having the Chair of the Council of Economic Advisers weigh in on urban issues, especially zoning, is significant.

In his remarks, Furman links what’s happening in cities to two big macroeconomic problems: the slowdown in productivity growth, and the rise of income inequality.

The argument on productivity is this: By bringing people together, cities facilitate the formulation and application of new ideas that propel innovation, creating new products and lowering costs. These so-called “agglomeration economies” are a major factor in lifting productivity. For a variety of reasons, some cities are more productive than others. Historically, people have moved from less-productive regions to more-productive ones, because places with higher productivity tend to have better wages. In the process, they increased the productivity of the country as a whole.

But since the 1970s, many of the most productive cities have greatly limited the expansion of their housing supply, and thus the number of people who can move there. In other words, they hold back population growth in the very places that are the biggest contributors to economic opportunity. Fewer people end up living and working in the most productive cities, and more people end up living in somewhat less productive cities. Two Berkeley economists have estimated that the total value of lost output due to this lower efficiency because some highly productive cities aren’t as large as they might be over a trillion dollars annually.

The constrained housing supply argument recognizes that a major source of upward economic mobility is the ability of Americans to physically relocate to places with greater economic opportunity. Furman notes that physical mobility has decreased in the US over the last several decades, and that in-migration has been suppressed in exactly those places with the highest levels of productivity. That means fewer opportunities to move up the income ladder, especially for the lowest income segments of the population, who are most sensitive to housing costs in their decisions about moving.

The argument on inequality is based partly on this observation about the constrained housing supply in highly productive cities, and partly on the work of Raj Chetty and his colleagues at the Equality of Opportunity project. Intergenerational economic mobility—measured as the likelihood that children born to families in the lowest income quintile will see a substantially different economic outcome as adults—varies substantially among metropolitan areas. Chetty found that one of the important correlates of this kind of economic mobility was whether a metropolitan area had a high level of economic segregation: having high income and low income people live in widely different parts of the metropolitan area. Again, local zoning plays a key role in determining whether housing opportunities are widely available within metropolitan areas for persons of all income levels.

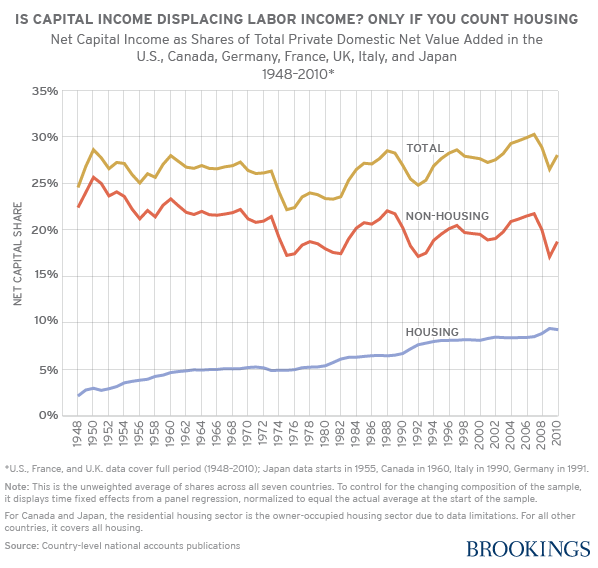

Although he didn’t mention it in his speech, Furman could also have pointed to the work of Matthew Rognlie. Rognlie has shown that capital gains from housing—that is, the money homeowners earn in part by using zoning to increase the price of their property—are a major component of rising inequality between the upper end of the income distribution and everyone else. All of the net increase in capital’s share of income has been in the form of returns to housing. Given the important role of housing in driving income inequality, it’s important to pay attention policies—like local land use restrictions—which can drive up housing costs.

To us at City Observatory, these observations show the pervasive and powerful effects of what we’ve called the nation’s shortage of cities. The high and rising demand for urban living is daily colliding with our limited ability to rapidly expand the supply of great cities, great urban neighborhoods, and housing within those cities and neighborhoods. Part of the problem is just that demand can—and has—changed much more rapidly than supply—people’s tastes change quicker than we can build new houses, much less neighborhoods and cities. And a key factor impairing our ability to meet this demand is local land use regulations.

As Furman calls out, all the things that impede increments to housing supply including density restrictions, parking requirements, prohibitions on mixing different uses in a single neighborhood—contribute to higher prices, less mobility, lower economic growth and greater inequality.. In fact, the “modern” approach to planning has made the most desirable, most valuable most in demand kind of neighborhood—walkable, dense, mixed use urban development—actually illegal in most places.

While Furman’s speech is a welcome acknowledgement from the most authoritative economic voice in the federal government of the importance of cities, his suggested federal actions for dealing with the problems he identifies are pretty small bore.

Furman sketches out three federal initiatives: the administration’s new rule on Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing), which would block local policies that locate new public housing in ways that reinforce patterns of segregation; a new $250 million loan fund for affordable multi-family housing projects; and a proposal—probably doomed—by the administration to make grants to local governments to overhaul their zoning ordinances. While these are steps in the right direction, they are just the tiniest of baby steps.

Furman does little to acknowledge the prodigious federal role in promoting and reinforcing the local status quo that he recognizes is so damaging. For decades, federal tax, expenditure, and financial policies have made home ownership the de facto preferred means for American households to build wealth. The efforts have been buttressed by everything from policies of the FHA which discouraged multi-family housing in established neighborhoods, and highways that subsidized sprawling, low-density single family owner occupied housing developments. Even the nationwide adoption of zoning traces its roots back to Herbert Hoover’s efforts at the U.S. Department of Commerce in the 1920s to develop and propagate model zoning codes. As long as homeownership remains effectively the only federally sanctioned vehicle for wealth accumulation for lower- and middle-income families, is it any wonder that they devote enormous energy to protecting their investments?

It’s definitely fair to say that local zoning is a major factor in shaping our shortage of cites. But it’s equally important that local zoning is underpinned by a web of federal policies that make it difficult to do anything different from what we’ve done. Now that CEA has puts its finger on this problem, we hope that it will keep working and come up with a set of policy recommendations that is fully commensurate with the scale of the issues involved. This high level federal interest is long-overdue and well-warranted, but there’s much more work to be done.