Eliminating exclusively single-family zones won’t provide enough density: Recognizing the limits of “missing middle” as a solution to urban affordability

At City Observatory, we’re excited as anyone that there seems to be a growing groundswell of support around the nation for eliminating exclusively single-family zoning. Minneapolis has garnered national headlines by legalizing duplexes and triplexes in zones once reserved for detached housing. Oregon is considering a measure that would ban exclusive single-family zoning in cities over 10,000 statewide.

These measures are an important step forward to facilitating some of the “missing middle” housing types that provide a range of affordable housing and greater income diversity, in what otherwise might be exclusive and expensive neighborhoods. This is an important symbolic and rhetorical advance for the YIMBY movement, and a key breakthrough in changing the way we talk about neighborhoods and housing: single family zoning is no longer sacrosanct and politically untouchable.

But, it must be said, this is only a first step.

Legalizing accessory dwelling units, duplexes, triplexes and fourplexes does hold the promise of adding to affordability while injecting some very “gentle density” into single family neighborhoods. But it is far from up to meeting the scale of our housing affordability problems. For that, we need to build larger multi-family buildings, including apartments.

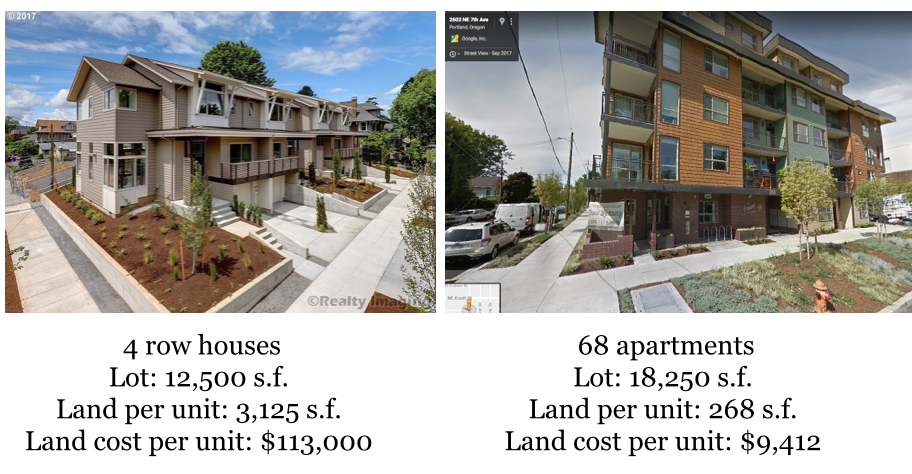

Row houses vs. apartments

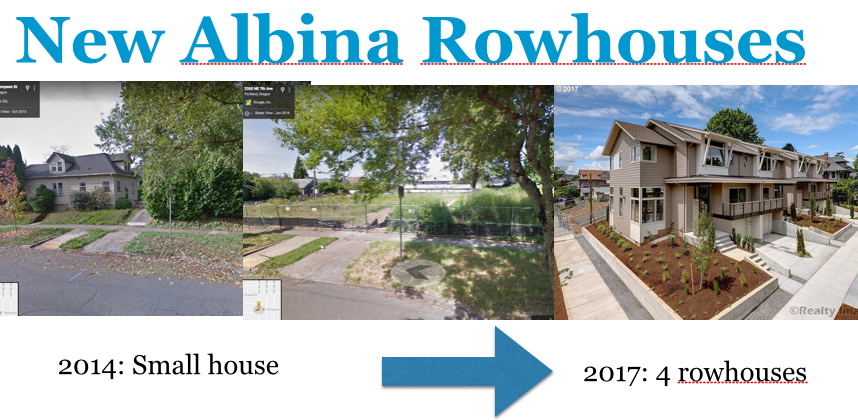

Consider two buildings, both built on similar sized lots, just three blocks apart on Northeast Seventh Avenue in Portland. Both were completed in the last two years. Both are on relatively large corner lots that were purchased by developers in 2014. At the corner of Seventh Avenue and Thompson Street, a developer tore down a small existing home on a 12,500 square foot lot and built four adjoining row houses called the “New Albina Rowhouses.”

Just down the street, a second developer demolished a derelict 1920s era gas station on an 18,250 square foot lot, and built a six story, 68 unit apartment building, called “The Russell.”

Just down the street, a second developer demolished a derelict 1920s era gas station on an 18,250 square foot lot, and built a six story, 68 unit apartment building, called “The Russell.”

Both of these projects added more housing in a high-demand area. It’s worth comparing their cost and their impacts on the supply and affordability of housing in the neighborhood.

The fourplex is a great example of “missing middle” development, and relatively low-impact in-fill, while the six-story apartment building is an exemplar of the kind of development that neighborhood associations love to hate and indeed, neighbors protested strongly against this building when it was proposed. (As a sidelight, because the site was zoned for apartments, under Oregon’s land use laws, the developer was able to proceed with the project essentially by-right, in spite of neighbors objections.)

Apartments are more affordable due to lower land costs per unit

Both lots sold for almost the same price prior to development in 2014, according to property tax records: one sold for $35 per square foot, the other for $36. This has a straightforward implication for affordability. Households who want to live in the fourplex have to buy about ten times as much land to accomodate their housing unit as households who want to live in the apartments. Each row-house needs about 3,175 square feet of land (at $35 per square foot, about $113,000 of land), while each apartment needs just 268 square feet of land (or about $9,400 of land per unit).

From the standpoint of housing supply, there’s about a ten-fold difference between the two projects. The fourplex provides four housing units (a net gain of three from the previous small, single family home of the site). The six-story apartment building provides 68 housing units on a lot about 50 percent larger. (All of these were a net gain as the site had no housing previously). On a per square foot basis, the apartments provide about ten times as many housing units for the neighborhood. That means the apartments soak up ten times as much demand, which would otherwise lead to households bidding up the price of housing in the neighborhood and elsewhere in the city. To accomplish the same increment to housing supply, you’d need to build about twenty fourplexes in place of existing single family homes, as each fourplex yields a net gain of 3 housing units.

Apartments mean less widespread disruption and demolition

The space efficiency of apartments is actually a boon if you’re looking to avoid widespread neighborhood disruption and minimize demolitions of existing homes. In contrast to a four-plex for single family in-fill process, every “Russell” that we build avoids about 20 demolitions of single family homes. The “Russell” has a bigger impact on adjacent properties than the a single row house project, but you’d need 20 more row house projects, somewhere, to provide as much housing as the Russell.

The great thing about apartments is you don’t need a lot of land to build much, much more housing. There are plenty of gas stations, parking lots, under-utilized strip malls and similar properties to accomodate thousands of apartments in every city in the US–if the zoning and development approval processes allow it.

There are significant opportunity costs to underbuilding density in prime urban locations. Both the Russell and the Albina row houses will likely still be standing in fifty or 100 years. It probably won’t make economic sense to demolish the row houses and build apartments on that site any time. So committing that site to a fourplex, rather than a Russell-sized building forecloses that possibility for many decades–and means that either apartments (or many more fourplexes) will have to be built on less desirable sites in the meantime.

There’s a good argument to be made that we’re underbuilding density in many locations where it makes sense. Neighborhoods with great transit, a mix of commercial uses, and high levels of walkability may justify more than just a duplex or triplex on a particular site. We ought to be think about the long term, what the demand for the neighborhood is likely to be in 2050 or even 2075, rather than in terms of the 20 year time horizon of most housing affordability analyses.

Given that the average lifetime of a building is 50 or 100 years, building a duplex now may foreclose building 12 or 20 or 50 units on the same site for several decades. And cities and neighobrhoods don’t tend to grow my incremental changes to the density of buildings, i.e. with single family buildings in one decade, giving way to duplexes in the next decade, fourplexes in the following decade, garden apartments in the next decade, and mid-rise apartments later. It’s far more economic to replace one or two single family homes with several dozen apartments, and leave the rest of the neighborhood untouched. Not to mention more politically palatable.

It’s helpful to remember that most of the neighborhoods that exhibit a mix of housing types, including duplexes, triplexes and fourplexes were originally built that way, because early zoning codes (especially prior to World War II) didn’t prescribe only single family buildings. It’s rare to see a neighborhood completely retrofitted with just slightly higher density. Allowing duplexes, triplexes and fourplexes is the sort of thing that is mostly likely to promote affordability and mixed income in peripheral or suburban or greenfield locations than it is in built up urban neighborhoods.

None of this should discourage us from celebrating the important political, rhetorical and practical victory of ending the long established bans on duplexes, triplexes and fourplexes in most residential areas. That’s a huge step forward. But dealing with housing supply and affordability will inevitably require a strategy to make it easier to build apartments in more places. We’re going to need a bigger boat.