I live in Chicago. In Chicago, like pretty much everywhere, people complain about traffic. Almost every day, our roads and highways get congested at rush hour, leaving people crawling along supposedly high-speed corridors, wasting time, money, and gas. This is what it looks like on a typical Monday at 5:35 pm:

Obviously, no one is happy about this. So some people argue that we ought to build more highways. If the problem is that there are too many cars for the number of highway lanes, then surely building more highway lanes will improve the situation! In fact, just recently our governor announced that he was planning on adding at least one lane in each direction on I-55, which runs southwest out of the Loop.

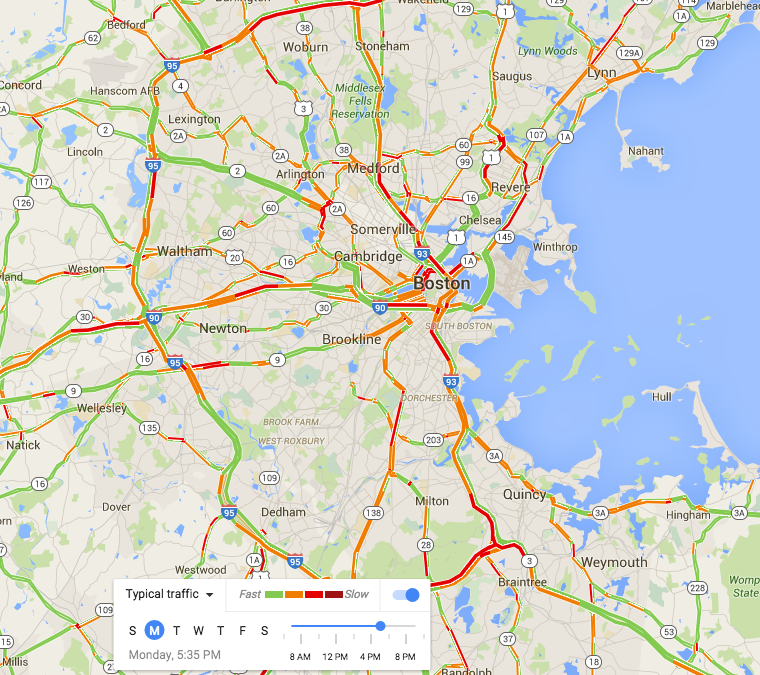

It turns out that it’s true that Chicago has relatively few highways: by one measure, fewer than any other major metropolitan area, with just 0.33 highway lane-miles per 1,000 people. So let’s go on a Google-assisted fact-finding mission to some other cities with more highways to see if they’ve solved their traffic problems. Here’s Boston, which, at 0.62 highway lane-miles per 1,000 people, has almost double the highway capacity of Chicago:

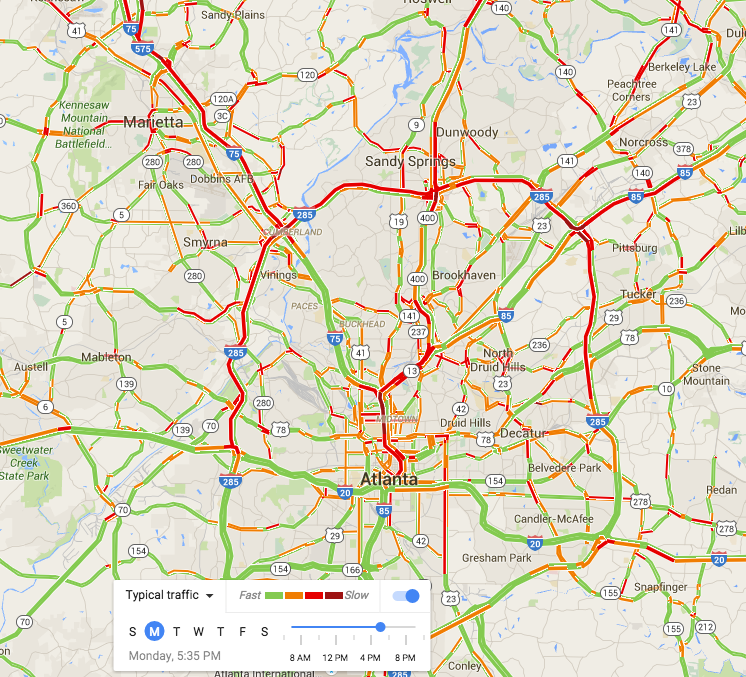

Hm. That still looks pretty bad. Maybe the issue, though, is Boston’s famously narrow streets in its dense central city. (After all, people also blame Chicago’s congestion on too many people packed into too little space.) So here’s Atlanta, which has a similar number of highway lane-miles per 1,000 people (0.56), but is way less dense and has way bigger surface streets:

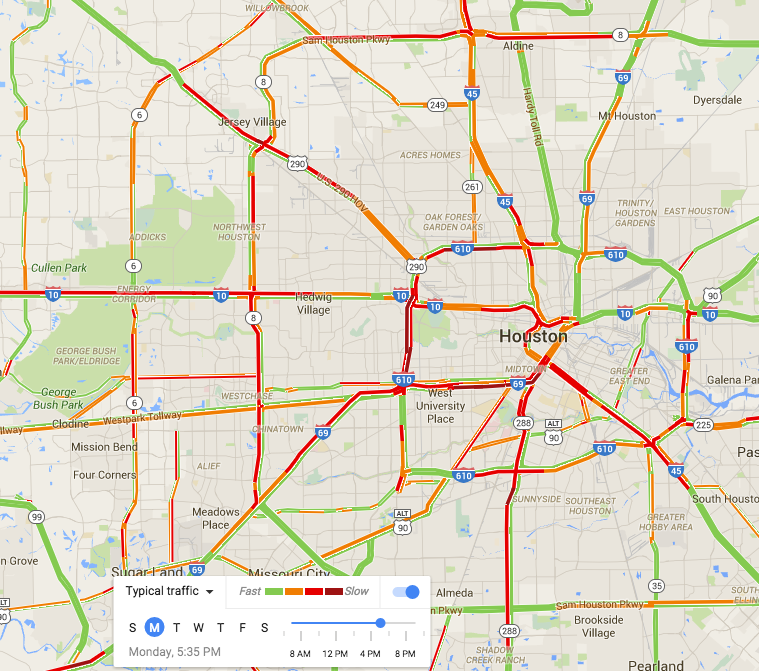

No dice. Okay, let’s go for even more highways. Remember, at this point we’ve nearly doubled Chicago’s highway capacity, spending many tens of billions of dollars, declaring eminent domain on hundreds of thousands of homes and businesses, and tearing apart dozens of neighborhoods. But what if we nearly tripled Chicago’s highway capacity? Houston has 0.82 highway miles per 1,000 residents, massive surface streets, and very few high-density areas like Boston or Chicago. Here’s what their rush hour looks like:

Obviously, this is not exactly a scientific study. Fortunately, however, other people have done those, and they find something similar: more road capacity does not necessarily mean less congestion. If a wider highway makes traffic flow faster, then some number of people who had been using other methods of transportation, or just making fewer trips, will start driving on the highway—adding more cars until traffic gets so bad that they stop. Over the longer term, additional highway capacity encourages developers to build ever farther into the suburban periphery, advertising the transportation benefits of being right next to a big highway that can bring you into the metropolitan area. The people who buy homes out there are then locked into driving longer and longer distances to get to work, go shopping, and meet people, each of which ends up increasing traffic congestion. That’s a big reason why people in Houston drive, on average, 12.2 miles to work, as compared to 10 in Chicago—even though Houston’s metropolitan area has almost a third fewer people than Chicago’s.

The problem, fundamentally, is one of space: cars take up a huge amount of physical space per person, compared with other kinds of transportation. In smaller cities, you might be able to accommodate them without total gridlock, at the cost of downtowns that are mostly parking lots, and streets that are unsafe for children or the elderly to cross. But as metropolitan areas grow, it simply becomes impossible to create enough space for cars. Even cities that have grown up almost entirely in the automobile era, and have catered to it in about as extreme a way as you can imagine, suffer from daily traffic jams.

When you’re sitting in traffic congestion, it’s natural to wish it away, and to imagine that with just a little more space, you could whisk yourself along at higher speeds. But if that’s the vision, it’s worth checking on other cities that have done just that. And it turns out that almost all of them, even ones that have double or nearly triple the highway capacity of a place like Chicago, still have the same problems. Maybe it’s time to look for different solutions.