A little while ago, in a post called “Sprawl beyond zoning,” we argued that even though Houston doesn’t technically have a zoning code, it still regulates the built environment in lots of ways that make it difficult or impossible to safely or conveniently get around without a car.

But we also promised to get into the ways that Houston’s lack of an official zoning code actually does allow for more flexibility, and densification, than the vast majority of American cities.

Or at least, it does now. In fact, much of the story of Houston’s densification begins with reforms adopted in 1999. Prior to that date, residential lots could be no smaller than 5,000 square feet: not such an extreme requirement in a country where plenty of suburbs demand, say, a quarter acre or more (nearly 11,000 square feet), but still big enough that, combined with wide roads and sprawling, parking-heavy commercial developments, real walkable density wasn’t quite possible. (Chicago’s Bungalow Belt neighborhoods, which maybe skirt the lower threshold of “walkability” with single family homes, are built on lots that are generally 3,250 square feet.)

But just before the turn of the millennium, Houston decided that within its inner belt highway, residential lots could be as small as 1,400 square feet. (Of course, leave it to Houston to define even a radical pro-urban reform with reference to an expressway.) That decision set of an explosion of “townhouse” type developments in inner neighborhoods, adding significant amounts of housing while retaining, generally, the basic form of a single-family home.

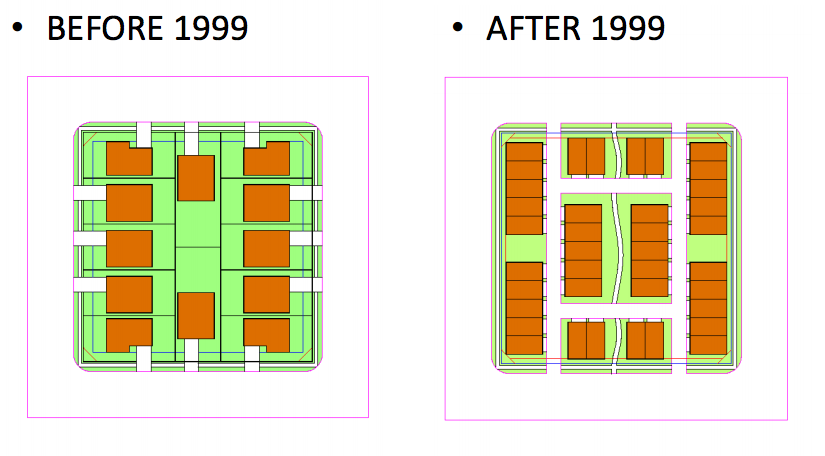

A handy diagram from this slideshow from Barbara Tennant shows what this looked like from the perspective of a city block:

And here’s a bit of what this looks like on the ground, via Google Streetview, with these two midcentury suburban homes in 2007…

…becoming four townhomes in the same amount of space by 2014.

It’s important to note that this change isn’t just special because, in most American neighborhoods, the original density of those two midcentury homes would be legally preserved in perpetuity—allowing, perhaps, larger single-family homes to be built on the same lots, but not more of them. It’s also special because of how it represents a more gradual, almost contextual ratcheting-up of density.

In most other cities, as we’ve covered, politics and the regulatory costs of building housing conspire to make almost all new development either of the density-neutral (or -negative) single-family home variety, or very large multifamily buildings. That’s because if you’re going to go through the process of getting a zoning variance, battling neighborhood opposition, and so on, there needs to be a big payoff on the other end—and building a three-unit building probably isn’t going to cut it. That means when cities do add density, they generally do it with buildings that are often quite a bit larger than their surroundings. Whether or not that’s objectively a problem is up for debate—but clearly, for many people, it is. But by making “missing middle” density legal to build as of right (at least in certain neighborhoods), Houston has seemingly attracted a lot more of it.

Of course, Tennant’s slideshow makes the point that Houston’s flexibility allows for some rather odd-looking buildings…

…but a lot of these new townhomes range from inoffensive to downright attractive, even by the snobbish standards of urbanists who prefer older, pre-World War Two cities.

These are human-scaled, street-focused developments built at a density that makes walking possible, even pleasant, minus the bayou weather. If you wanted to see what a genuine, 21st-century American urban neighborhood looked like, you probably couldn’t do much better.

Perhaps the greatest endorsement of the change was that it has not only been preserved, but expanded: In 2013, Houston eliminated the inside-the-beltway/outside-the-beltway distinction, and now the entire city has the denser, “townhouse” type regulations in residential areas.

But in the long run, the test of Houston’s exceptional policies will be to determine whether inner-city housing prices remain relatively low compared to other large American cities. For most of its history, most of Houston’s famously elastic housing supply has come from the same place as other Sunbelt metropolises that do have zoning: sprawl on the suburban periphery. In fact, studies comparing the development regimes of Houston with its zoned cousin, Dallas, found little to no difference.

But as far as I can tell, no studies have looked at the effects of Houston’s central city development since the adoption of townhouse regulations in 1999. An important research project in the coming years will be to see if Houston’s willingness to allow more housing—and especially missing middle housing—in the center of a growing metropolitan area can reduce the growth of housing prices and keep neighborhoods more diverse and affordable than they would otherwise be.