Rural and small town America faces some tough odds

In an article entitled: “How to save the Troubled American Heartland,” Bloomberg’s very smart Noah Smith shares his thoughts on how to revive the smaller towns of rural. For the most part, he’s in agreement with the ideas expressed by James and Deborah Fallows in their neo-Toquevilliean travelogue: Our Towns: A 100,000-Mile Journey into the Heart of America. The Fallows’ flew their small plane hither and yon across the nation, landing in the places that the pundits fly-over, and trying to glean signs of hope and lessons for success.

They visit towns such as Greenville, SC, and Allentown, PA and report that there are signs of life. Local leaders are valiantly working to revive their economies. And at least a few places are generating jobs, income and economic revival.

The key lessons, as suggested by Smith: local universities can train kids to succeed in the new economy and help create new jobs. In addition, communities ought to encourage immigration and look to form public-private partnerships. These are all plausible suggestions as to what small towns and rural areas ought to try. The problem with extracting “best practice” lessons from these relatively successful places is that it doesn’t answer the question of whether the strategy is replicable in different places or scales to all of rural America.

While essays like Smith’s and books like the Fallows’ treat the issue with a broad brush, the question is not what happens to the entire “heartland.” Some places, even rural, isolated ones will flourish, even if rural America as a whole is challenged or in outright decline. The bigger question is whether this is an exercise of sweeping rejuvenation, or something more like battlefield triage. The unstated objective of most rural economic development efforts to to restore some real (or imagined status quo ante, recapitulating a pattern of population and economic activity that existed in some prior year (usually an historic peak).

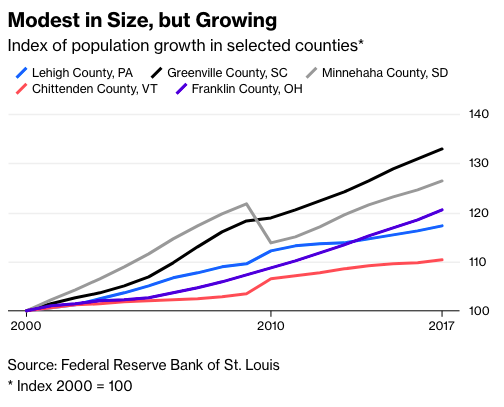

You can point to some rural and smaller metro places that are doing well. Smith presents this optimistic looking chart showing five smaller communities that have shown real growth since 2000.

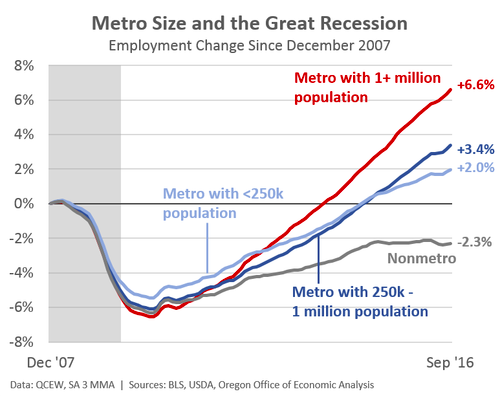

But when we look at the entire nation, grouped by population size, it’s apparent that big cities are powering national growth, and that as a group, small town and rural America is getting left further behind. As we’ve argued at City Observatory, much of this has to do with the strong connection between cities, talent, productivity and knowledge based industries. Smart people and the industries that employ them are increasingly gravitating toward urban locations, and are more successful there than in rural ones.

As a group, the nation’s non-metropolitan areas had not fully recovered from the Great Recession as of September 2016, according to data compiled by the Oregon Office of Economic Analysis. Although larger metros experienced proportionately larger job losses in the recession, they’ve collectively grown faster in the recovery, with metros of a million or more population growing almost twice as fast as smaller ones.

There are some stellar examples of successful rural places. Usually they’ve parlayed a signature asset, like an outstanding university or great quality of life into the nucleus of a new economic engine. But these tend to be exceptions.

While this has worked and will continue to work in some rural communities, it’s far from a general prescription for success. The fact that a few rural communities succeed doesn’t mean than these tactics will work everywhere. Noah Smith is reminded of the key role that Pike Powers played in organizing such a partnership in Austin. But Austin was also capital of a large state, an established tech center and home to a huge university. (By the way: every economic development effort I’ve ever seen, good, bad or wildly unsuccessful bills itself as a public-private partnership).

Much of the challenge in rural America is about a re-shaping of economic activity. Key service functions are becoming more centralized as the somewhat larger towns emerge as the medical center, the retail center or the university town for a rural region. The only thing worse than having the WalMart in your town is having it in a neighboring town. There are winners and losers in the rural landscape as this process unfolds.

Having a university is a valuable asset, but essentially we’re not building any new ones, especially in small rural communities. The same holds for having the region’s principal medical center. So if you’ve got one of these, great: If not, expect to see economic activity, kids, opportunity and entrepreneurship gravitate to the places that do.

What’s odd is that Smith’s telling overlooks some of the principal forces underpinning the economies of rural and small town America: cheap housing, social security and farm subsidies. Even as urban areas become more congested and expensive, housing in rural places is affordable. The foundation of a growing number of rural economies is the steady flow of funds from Social Security and Medicare, both to a rural region’s retirees, and to other retirees they might attract from expensive cities. Medicare (and Medicaid) revenues come disproportionately from cities and are spent disproportionately in relatively rural areas (which are older and poorer). And while the federal government has nominally eschewed most industrial policies, it continues to prop up agriculture through a combination of farm subsidies and support for infrastructure projects, like irrrigation and low cost power. In effect, we do have a federal policy for rural America-even if we don’t acknowledge it as such. The likely cuts to these and other federal programs necessitated by the recent tax cuts and ballooning federal deficit are likely to have a disproportionate effect on rural America.

There will continue to be occasional bright spots in the rural economy, but in most places, its beyond their means to think about job creation on a scale that’s going to reverse the slow process of decline.