What City Observatory did this week

When NIMBYs win, everyone loses. Two land use cases from different sides of the country are in the news this week. In both cases, local opponents of new housing development have succeeded in blocking the construction of new apartments in high demand neighborhoods. The high profile case is in Palo Alto, California, near Silicon Valley, where local homeowners managed to subject a 60 unit senior affordable housing project to a local referendum, and killed it. Now the site is home to newly built $5 million mini-mansions. With fewer and more expensive homes, the area will continue to be an enclave for the wealthy.

Meanwhile in working class Inwood, in Northern Manhattan, local residents have one a first-round court victory challenging the upzoning that would have allowed more market rate apartments, as well as set aside of affordable units. The court found that the city had failed to contemplate the impacts on the neighborhood’s racial makeup. What that misses, in our view, is that not approving upzoning in Inwood will also have a significant impact on the neighborhood’s affordability, and thereby, its demographic composition. Blocking new housing doesn’t keep a neighborhood affordable; actually its just the opposite: the more constrained the housing supply, the worse the affordability problems, the greater likely displacement and the more sweeping the demographic changes. That happens whether the NIMBYs at work are wealthy homeowners or struggling renters.

Must read

1. Whose streets? Cars’ streets. In the wake of the growing public debate on the structural racism embedded in so many of our institutions, it seems like a good time to revisit this excellent analysis of our transportation system written by Ben Ross in 2014. The way we’ve built our roads, particularly in suburbs, where a growing number of low income families and people of color are living, creates an environment that is deadly or dangerous to those who can’t drive or don’t own cars. Suburban roads incentivize and privilege high speed car travel, with few cross walks and sparse transit service, and when they are killed in collisions, pedestrians are often blamed.

The full weight of ninety years of car-first engineering bears down [on the suburban poor] as they make their way to and from decaying apartment complexes and aging tract houses. Long walks to the main road, unprotected dashes across wide highways, and perilous waits at bus stops on unpaved shoulders are a daily routine. A landscape created for affluent motorists becomes an oppressive burden in its decline.

The problem is compounded by car-oriented laws that are routinely used to harass and intimidate people of color. “Jay-walking” becomes a code-word for blaming pedestrians hit and killed by cars, and a reason police can use to detain or arrest citizens: Michael Brown was gunned down by a policeman in Ferguson, Missouri after being stopped for allegedly jay-walking. As Ross relates, the pedestrian hostile suburban environment is no accident: it’s literally mandated by a host of engineering rules and standards. If we’re going to overcome racism, we’ll need to change these rules of the road.

2. Cities will survive. Richard Florida weighs in on the long-run implications of the pandemic for cities. There’s lots of hyperventilating and pessimism about urbanism, but Florida isn’t having any of it. Cities have weathered similar challenges in the past and emerged even stronger; the decisive agglomeration advantages of being in cities overwhelms the perceived disadvantages of density. Florida is also quick to note that today’s unrest over racial injustice is very different than in the 1960s; its a racially and economically diverse group of protestors fighting for more just cities, and amounts to a powerful reason for hope, and not the polarizing paroxysm of fear.

New Knowledge

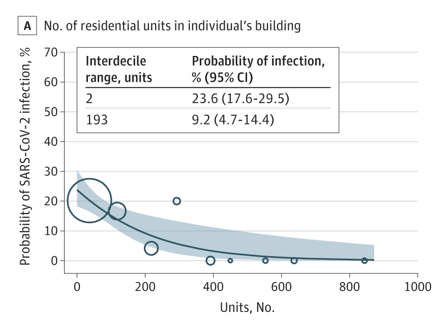

More evidence that density has little to do with Covid-19 prevalence. New York City tested all women who delivered children in NYC hospital, providing a comprehensive sample of women from different parts of the city. Researchers looked at the correlation between the likelihood of testing postive for Covid-19 and various neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics. They found positive links between housing over-crowding and the odds of being infected, but a negative relationship between the number of units in a building and offs of being infected. People who lived in buildings with more units were less likely to have Covid-19.

The study found no statistically significant relationship between population density and the probability of having a Covid-19 infection (i.e. women who lived in higher density neighborhoods were no more or less likely than women from lower density neighborhoods to test positive for the virus.

The study found no statistically significant relationship between population density and the probability of having a Covid-19 infection (i.e. women who lived in higher density neighborhoods were no more or less likely than women from lower density neighborhoods to test positive for the virus.

In the News

The Pittsburgh Business Times wrote about our report Youth Movement, and its relationship to the market for new apartments in that city.

Greater Greater Washington pointed its readers to the Youth Movement report.