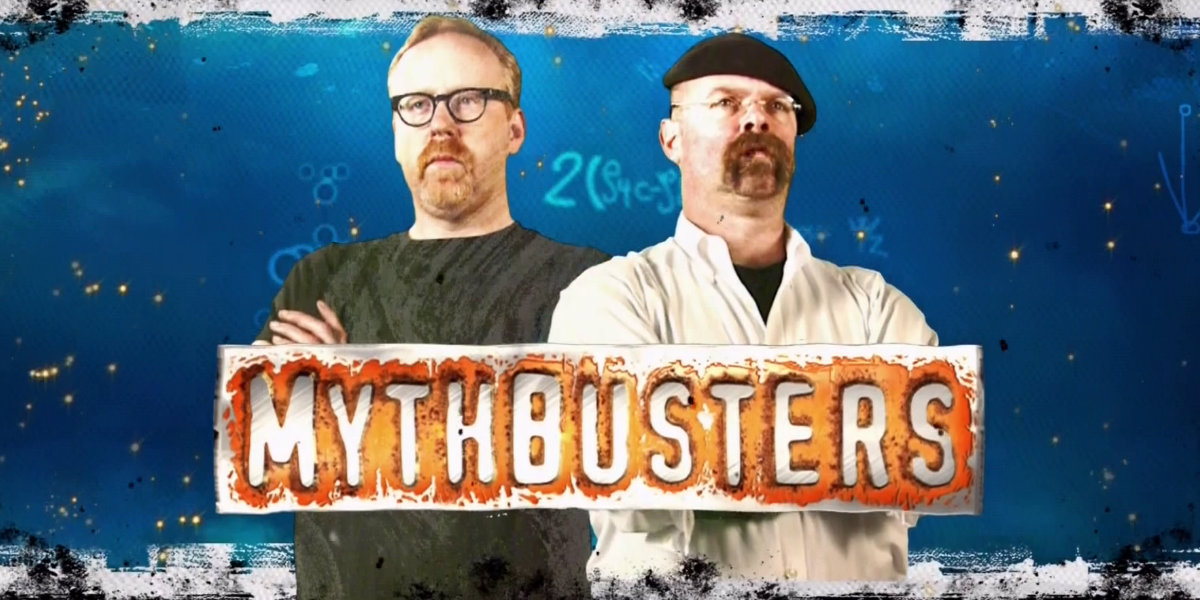

After fourteen seasons, Discovery Channel’s always entertaining “Mythbusters” series ended last year. If you didn’t see the show-and it lives on at Youtube, of course–co-hosts Adam Savage and Jamie Hyneman constructed elaborate (often explosive) experiments to test whether something you see on television or in the movies could actually happen in real life. (Sadly, it turns out that you can’t make a bullet curve no matter how fast you flick your arm.)

At City Observatory, we feel compelled to enter into this void, and we’ll start by doing our own urban myth-busting. First up: Does building new high-priced apartments, affordable only by middle- and upper-income families, make housing less affordable for lower income households?

We’ve heard this claim time and again in public hearings: new rental housing charges higher rents than existing apartments, and must therefore be making affordability problems worse. Business Week’s Noah Smith shared the lament of the misunderstood economist who confided in a progressive friend that he favored building new market-rate (i.e. high priced) housing in San Francisco:

I was talking to a friend the other day, a San Francisco anti-eviction activist, and said that allowing more housing construction in the city would be a great way to lower rents. She looked at me in horror, blinked and asked “Market rate?” I nodded. She was speechless.

My experience was far from unusual. To my friend and many others, it has become an article of faith that building market-rate housing raises rents, rather than lowers them. The logic of Econ 101 — that an increase in supply lowers price — is alien to many progressives, both in the Bay Area and around the country.

Even Harvard University’s Joint Center on Housing Studies reprised this line in one of their recent reports: “50 percent of rental households make less than $34,000 per year, but only 10 percent of new multi-family units are affordable at this income.”

From this statistical observation, it’s a short leap to the conclusion that building new housing is part of the affordability problem. The Wall Street Journal reported that “much of the new supply is aimed at higher-income renters.” In May, the Journal ran a story claiming: “A focus by builders on high-end apartments helps explain why rents are soaring across the country.”

On its surface, this sounds terrible. But the key context missing here is that in the United States, we have almost never built new market-rate housing for low-income households. New housing—rental and owner-occupied—overwhelmingly tends to get built for middle- and upper-income households. So how do affordable market-rate housing units get created? As new housing ages, it depreciates, and prices and rents decline, relative to newer houses. (At some point, usually after half a century or more, the process reverses, as surviving houses—which are often those of the highest quality—become increasingly historic, and then appreciate.)

What really matters is not whether new housing is created at a price point that low- and moderate-income households can afford, but rather, whether the overall housing supply increases enough that the existing housing stock can “filter down” to low and moderate income households. As we’ve written, that process depends on wealthier people moving into newer, more desirable homes. Where the construction of those homes is highly constrained, those wealthier households end up bidding up the price of older housing—preventing it from filtering down to lower income households and providing for more affordability.

This isn’t theoretical: As we’ve discussed before at City Observatory, the vast majority of today’s actually existing affordable housing is not subsidized below-market housing, but market-rate housing that has depreciated, or “filtered.” Syracuse economist Stuart Rosenthal estimates that the median value of rental housing declines by about 2.2% per year. As its price falls, lower-income people move in. Rosenthal estimates that rental housing that is 20 years old is occupied, on average, by households with incomes about half the level of incomes of those who occupy new rental housing.

In its 2016 report on the state’s housing crisis, the California Legislative Analyst’s Office noted that as housing ages, it becomes more affordable. Housing that likely was considered “luxury” when first built declined to the middle of the housing market within 25 years. Take the 1960s-era apartments built in Marietta, a suburb of Atlanta: When they were new, they were middle to upper income housing, occupied by single professionals, gradually, as they aged, they slid down-market, to the point where the city passed an $85 million bond issue to acquire and demolish them as a way of reducing a concentration of low income households in the Franklin Road neighborhood.

Another critical point is that if we don’t build more housing at the high end of the market, those households don’t just disappear, they take their demand “down-market” and bid up the price of housing that would otherwise filter down to middle and lower income households. That’s exactly what the Montgomery County Maryland housing department reports is happening there:

The shortage of rental housing at the high end of the market creates downward pressure on less affluent renters, the study found, because when higher-income households rent less expensive units, lower-income renters have fewer affordable choices. Cost-burdening is linked with this unbalanced market, especially at the lower end of the income spectrum.

Ironically, this problem persists in Montgomery County in spite of its widely touted inclusionary housing requirement that forces builders of new apartments to set aside a portion of them for low and moderate income households.

New Cars are Unaffordable to Low Income Households, too

Here’s another way to look at the connection between affordability and the price of new things: cars. (After houses, cars are frequently the most expensive consumer durable that most American’s purchase.)

Exactly the same thing could be said of new car purchases: Most new cars aren’t affordable to the typical household either—the average sale price of a new car is nearly $34,000.

In fact, using the same kind of approach that Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies used to assess rental affordability, Interest.com reports that the median family can afford to buy the typical new car in only one large metropolitan area. Similar to the “30 percent of income” rule widely—and in our view inappropriately—used to gauge housing affordability, they assume that the typical household makes an 20 percent down payment, finances its purchase over four years and pays no more than 10 percent of its income for a car payment. They report in most metros that the typical family falls 30 to 40 percent short of being able to afford a new car. So most households deal with car affordability pretty much like they deal with housing affordability: by buying used.

When it comes to anything new and long-lived, higher-income households buy most of the output. According to Bureau of Labor Statistics data, households in the two highest income quintiles accounted for about 67 percent of the purchase of new cars in the US in 2001. New car buyers are getting progressively older, and are more likely to be high income. According to the National Automobile Dealers Association, the median new car buyer is 52 years old and has an income of about $80,000, compared to an average age of 37 and an income of $50,000 for the overall population.

But there’s no outcry about America’s “affordable car crisis.” The reason: high-income households buy newer cars; most of the rest of us buy used cars—which are more affordable after they’ve depreciated for a while.That’s even more true of housing, which is much longer lived. Nationally, 68 percent of the nation’s rental housing is more than 30 years old—so only about 10 percent of the nation’s renters live in apartments built in the last decade.

New houses, like new cars, are sold primarily to higher income households—and affordability comes from getting a bargain when the car (or house or apartment) has depreciated. Building more high priced new apartments, in fact, is critical to generate the filtering down of older housing that constitutes the affordable housing supply.

This myth is busted: building more high end housing doesn’t make housing less affordable.