A new study claiming ride-hailing increases crashes and deaths leaves some questions unanswered.

A new study from the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business makes the provocative claim that the advent of ride-hailing services like Lyft and Uber has actually led to an increase in car crashes, and related injuries and deaths. If true, this is a pretty stunning downside to this new technology.

We’re skeptical that this paper has it right, for three reasons:

- The study leaves out the effect of lower gas prices and increased driving on crash rates.

- Rural areas–which essentially don’t have ride-hailing services–saw even bigger increases in crashes than cities with ride-hailing.

- And the study doesn’t try to correlate the increase in crashes to either the times or the places that ride-hailed vehicles are most used, which would be a much more powerful indicator of a safety effect.

The paper, The Cost of Convenience: Ridesharing and Traffic Fatalities, is written by John Barrios of the University of Chicago and Yael V. Hochberg and Livia Hanyi Yi of Rice University. It looks at the roll-out of ride hailing services to different cities and changes in local crash rates. The key method behind the study is a “difference in difference” analysis of crash trends across cities. The authors basically look at the date at which Uber and Lyft introduced their services in different cities and look to see if there’s any correlation between the addition of service and a change fatality rates. It finds that there has been a positive correlation between these two events. They conclude that the advent of ride-hailing is associated with about a 2-3 percent increase in fatal crashes. Their paper argues that ride-hailing has increased vehicle miles traveled, and therefore led to more crashes.

To be clear, the authors have labeled this a preliminary draft, which clearly indicates that they’re open to comments and criticism. In that spirit, we have some questions.

Leaving out gas prices and vehicle miles traveled

First, to be clear, this is a study that shows correlation, rather than causation. Essentially, at the time that cities were adopting ride-hailing, there was an increase in fatal crash rates. Clearly, it’s possible that ride hailing was a contributor to the increased volume of traffic. But other things were increasing traffic during that time, and moreover, the roll-out of ride hailing happened pretty much everywhere in a relatively short period of time. So one challenge for the statistical analysis is the actual dearth of difference among cities in introduction dates. Following the well established “S-curve” of innovation, nearly all cities saw ride-hailing service introduced in just two years. The fact that the service spread so rapidly means that there isn’t a huge amount of variation among cities on that factor. As the Barrios-Hochberg-Yi paper makes clear virtually all of the uptake in ride-hailing took place between early 2014 and the end of 2016.

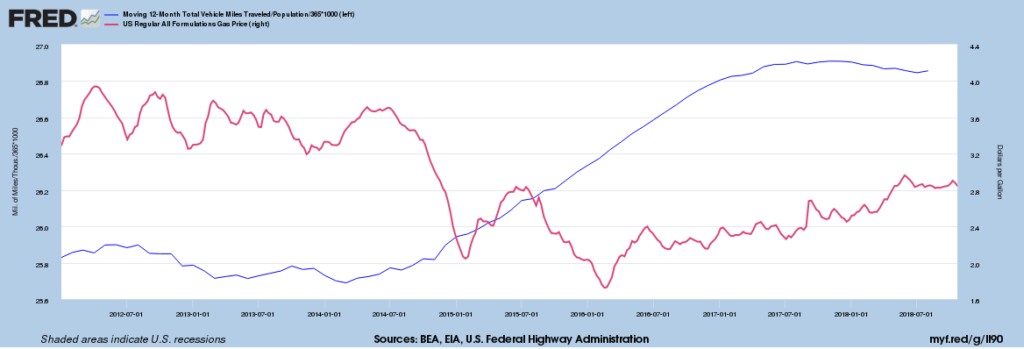

More importantly though, there was another big change that happened at exactly the same time that has a lot to do with crash rates. In the third quarter of 2014, gas prices fell precipitously. And, as we’ve chronicled at City Observatory, the decline in gas prices led directly to an increase in driving. Here’s the data from the US Department of Energy (gas prices, red line) and US Department of Transportation (per person vehicle miles of travel (VMT), blue line). When gas prices fell, driving increased.

More driving is a key reason why there’s been more dying. Moreover, there’s good work (pre-dating the existence of ride-hailing services) that shows that at the margin, the increase in driving occurs at those times and among those drivers who are riskiest. When gas prices get cheaper, both those who drive more, and the times at which they drive, are more prone to crashes. A detailed study of gas prices and crashes in Mississippi found that a 10 percent increase in gasoline prices was associated with a 1.5 percent decrease in crashes per capita, after a lag of about 9-10 months.

The decline in gas prices is a much more powerful explanation for the increase in vehicle miles traveled (and death rates) than is the advent of ride-hailing. A study that observes a correlation between higher crash rates and ride hailing, and asserts that the mechanism by which ride-hailing has increased crash rates is higher VMT should sort out the contribution of gas prices. As far as we can tell, nothing in the Barrios-Hochberg-Yi paper consider the effects of gas prices on driving levels and crash rates. This seems like a major limitation in this paper.

A counterfactual: Rural fatality rates rose even more

The Barrios-Hochberg-Yi paper makes much of the fact that crash and fatality rates were falling prior to the introduction of ride-hailing services and have increased since then. As we’ve argued that has a lot to do with the big decline in gas prices.

A logical way of dis-entangling the relative contributions of gas prices and the advent of ride hailing to the increase in crashes and fatalities is to look at variations in crash trends between urban and rural areas. Uber and Lyft are almost exclusively urban phenomena, and so rural areas, as a group, should be almost immune from whatever negative effects they cause on traffic crashes and deaths.

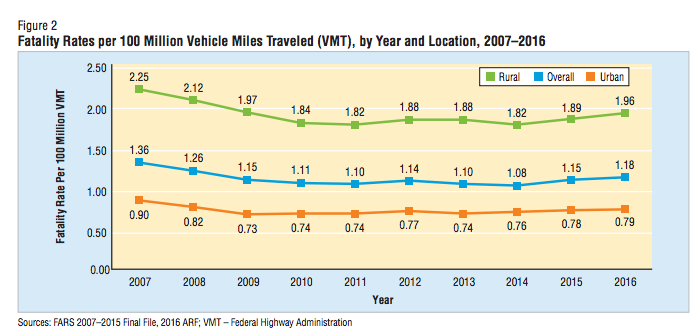

Here are the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration‘s data on urban and rural highway fatality rates per 100 million miles traveled over the past decade.

These show a couple of things. First, there’s a decline in fatality rates from 2007 through 2013, in both rural and urban areas, followed by an uptick afterwards. Second, the increase in crash death rates in rural areas is actually even higher between 2014 and 2016 (up 7.7 percent from 1.82 to 1.96) than it is in urban areas (up 3.9 percent from .76 to .79).

If ridehailing were responsible for an acceleration in crashes and deaths beyond that attributable to increased driving generally because of lower gas prices, one would expect just the opposite pattern (i.e. that the urban crash death rate would rise faster than the rural crash death rate where Uber/Lyft were not available).

The fact that rural crash death rates also rose, and actually rose faster than urban crash death rates is a reason to be skeptical of the claim that ride-hailing caused more crashes and deaths in cities.

Time and date and location effects

Analyzing the impact of ride-hailing on urban transportation systems is complicated by the fact that Uber and Lyft are not always forthcoming with the detailed data that would be needed to conduct an analysis. The authors of the Barrios-Hochberg-Yi paper weren’t able to get data on the number of drivers or riders or rides in individual cities over time from the two companies (which would have been the preferred way of measuring their impact on cities), and instead used the volume of google searches for the two company’s names as a proxy for the volume of ride-hailing activity over time.

That strikes us as a pretty crude measure. Even in the absence of actual trip data, it should be possible to construct much more reasonable tests of the impact of ride hailing, given well-documented variations in the temporal and spatial patterns of ride-hailing activity.

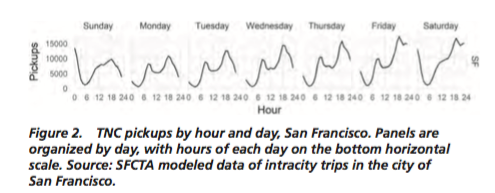

Ride hailing trips are heavily concentrated in time (peak hours, and weekend nights) and in space (in downtown areas and near airports). We reviewed a very detailed five city study on this in our commentary “Drinking,Flying, Parking, Peaking, Pricing.” As the report illustrates, there’s a strong pattern to ride-hailing use by time of day and day of week:

One of the most valuable aspects of fatal crash data is that it is coded with the exact date, time and location at which a crash occurs. Given that we know a great deal about the time and location of ride-hailing activity, and also about the time and location of fatal crashes, it should be possible to do a much more precise analysis of the correlation between ride-hailing and crash deaths that aggregating data at the city level by month or year.

For example, if the thesis of the Barrios-Hochberg-Yi paper is correct, and ride-hailing contributes to increased crashes, it ought to be correlated with the days of the week, times of the day, and locations at which ride-hailed vehicles are most present. For example, a high proportion of all ride-hailed trips occur on Friday and Saturday nights, while only tiny fractions of such trips are taken on mid-days on Tuesdays and Wednesdays. If ride-hailing were responsible for increased deaths, one would expect most of the increase to occur on those times when it was most active.

Similarly, ride-hailing activity is highly concentrated in city centers, and secondarily in and around airports. This pattern has much to do with the fact that parking is priced in cities, and that travelers to and from airports may not own a car in the city in which they are traveling, or find it expensive or inconvenient to rent or park one. Again, if our hypothesis is that ride-hailing has increased crashes, we would expect to find more crashes in those places in which ride hailing was prevalent, and expect no increase or a smaller increase in crashes where ride hailing was rare (i.e. low density suburbs).

More analysis is needed

The advent of ride-hailing is undoubtedly having some major effects on urban transportation, and deserves to be studied closely. It’s a hopeful sign that the author’s of this paper have characterized their work to date as “preliminary,” because there’s much more to examine. We hope that Uber and Lyft would recognize their interest in making more data available to researchers so that more precise analyses could be undertaken.

While this paper raises important and provocative questions, we think it needs to address three key questions before its conclusions can be taken seriously.

- First, we need to explicitly address the role of declining gas prices on vehicle miles traveled and crash rates.

- Second, we need to explain why rural crash death rates went up even more than urban ones.

- Third, we need to make much better use of the detailed temporal and locational data on crashes and determine whether there’s any connection between the times and places where ride-hailing is most used and the increase in crashes.