What City Observatory did this week

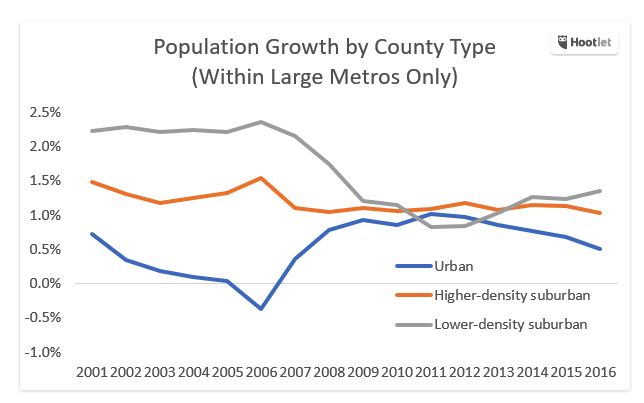

1. Is the urban revival over? A provocative (but highly misleading) headline in last week’s New York Times sits atop Richard Florida’s op-ed about the future of cities. Although Florida is really making the case that the urban revival is “fragile,” the headline says the revival is over. Actually, the evidence presented here doesn’t support that claim. Though growing somewhat slower than suburbs in the past two years, city growth has accelerated compared to the previous decade, while the suburban growth rate has slowed. More importantly, the continued growth in the demand for urban living shows up in the rising house price and rent premium Americans are paying to live in the densest, most urban locations. The biggest threat to the urban revival is our failure to build enough housing in the kinds of urban neighborhoods Americans most want to live in. Until we fix that problem, we’ll be bumping up against a shortage of cities.

2. Can you claim to be a LEED platinum city if your region is widening freeways? Washington DC just announced that it had been named the world’s first “LEED Platinum” city, based at least partly on the fact that the city has more LEED certified buildings per capita than just about anyone. But at the same time, the Washington area is just about to move forward with a $3 billion freeway widening project, that will likely further encourage car travel and sprawl. It’s another example of obsessing about the energy use of particular buildings (often just a few high profile ones at that), and ignoring how urban form and car-dependent transportation systems are the real threat to our climate.

Must read

1. The flaw with Net Zero. A growing number of innovative new green buildings, including (we think dubiously) some parking garages, make the claim that they are “net zero” consumers of energy. Lloyd Alter gives us some good reason to be skeptical of these Net Zero claims. The claim is usually based on the observation that the total value of energy that the building produces (say the output of solar collectors or wind turbines fastened to the building) is greater than the amount of energy consumed by the building itself. While that arithmetic may be accurate, it misses the fact that energy produced at one time (at noon in July) can’t be used at another time (say to heat and light the building in the dead of winter).

2. Is it legal to be a kid in the city? Adrian Cook lives in with his family in a condominium in Vancouver and writes the blog 5kids1condo. He recently taught his four oldest kids (ages 7 to 11) how to ride the city’s great public transit system to get to school. As Lenore Skenazy relates in her blog Free Range Kids, Cook’s efforts to let his kids roam freely drew the ire of the Canadian version of child protective services, who investigated Cook, and ruled that it was against the law for children under ten to be unsupervised by an adult, inside or outside a home. When the state insists that any form of parenting other than helicopter parenting is illegal, it’s committing another crime: depriving children of their agency and their opportunity to develop a sense of independence and responsibility.

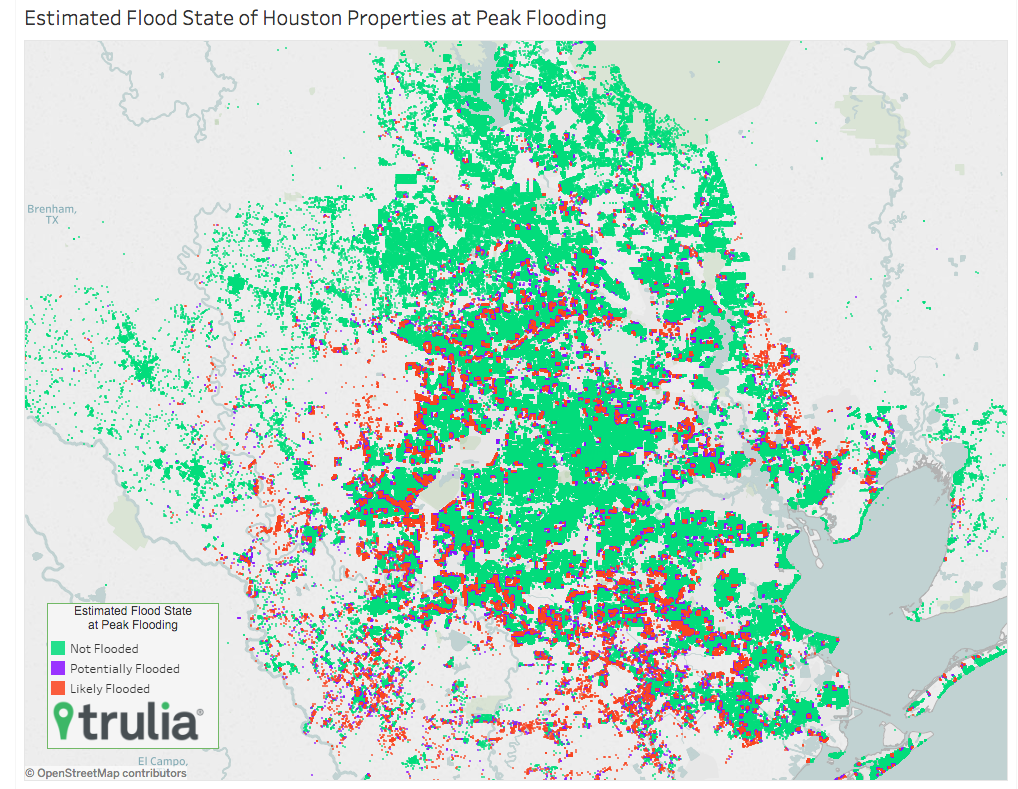

3. Is Houston a model city? Was it ever? Now writing for the New York Times, Emily Badger looks at the effect of Hurricane Harvey on Houston’s reputation for a certain kind of urbanism. Some, like Joel Kotkin and Wendell Cox remain steadfast that Houston’s sprawling development pattern is still the way to go. But in the wake of Hurricane’s damage, amplified by a lasseiz faire attitude, particularly with regard to impermeable surfaces and stormwater runoff, its harder to justify Houston as a model. At a minimum the city’s development pattern no longer looks like such a bargain if one adds in the $180 billion cost of repairing the damage from just this storm.

4. Where Houston flooded. Trulia’s Ralph McLaughlin has assembled the data to show the Houston neighborhoods most affected by flooding from Harvey. It shows just how extensive the damage was in the region.

New Knowledge

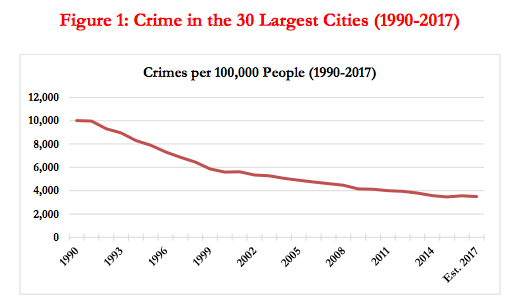

Crime rates hover near a three-decade low in 2017. A new report from the Brennan Institute of Justice looks at crime statistics from early 2017 for 30 of the nation’s largest cities, and projects overall crime rates for the year. They find that 2017 is on track to see about a 2.5 percent decline in crime from 2016, and that overall crime in 2017 is likely to turn out to be the second lowest rate recorded since 1990. They report that murder rates are down in many cities, including Detroit (-26 percent), Houston (-20 percent) and New York (-19 percent). The overall crime rate in the nation’s largest cities has fallen about 60 percent since 1990, from 10,000 crimes per 100,000 population, to fewer than 4,000.