What City Observatory did this week

1. Urban transportation’s camel problem. Naive optimism is the order of the day in speculating about the future of urban transportation. In theory, some combination of autonomous vehicles, fully instrumented city streets, and transportation network companies will help us solve all of our problems, from congestion to traffic fatalities to parking to accessibility for all. As Jarrett Walker has pointed out, these simplistic versions of a technological fix overlook a fundamental geometry problem in the capacity of city streets. To which we add what we call the “camel” problem. Demand for transportation isn’t smooth and even, its a two-humped camel, as most of our demand for movement occurs in a few morning and evening peak hours. Designing a technology to cope with camel-shaped transportation demand will be a big challenge for future technology.

2. Copenhagen: More than bike lanes. Copenhagen is a kind of cycling nirvana: just recently, the number of trips taken by bicycle exceeded car trips in that Danish city. Many Americans have made pilgrimages there, coming back with dreams of turning their cities into similarly bike-friendly environments. A recent story in the Guardian highlights what’s most obvious to visitors about the city’s success: they’ve built lots of bike lanes and city leaders are strong supporters of cycling. Those factors are both important, but this infrastructure plus leadership narrative leaves out an important set of facts about Danish tax policy. In Denmark, unlike the US, cars are expected to shoulder much more fiscal responsibility. Danes pay a 150 percent excise tax for new cars (more than doubling the cost of car ownership) and pay nearly $6.00 gallon for gas. Getting the prices right, as well as providing the infrastructure, are the secrets to this Danish cycling recipe.

3. You are where you eat. One of the hallmarks of a great city is a smorgasbord of great places to eat. Cities offer a wide variety of choices of what, where, and how to eat, everything from grabbing a dollar taco to seven courses of artisanally curated locally raised products (not to mention pedigreed chickens). The “food scene” is an important component of the urban experience. We quantify the foodie question in typical City Observatory fashion, reporting the number of restaurants per capita in each of the nation’s large metropolitan areas.

4. Peer effects: Help with homework edition. There’s a growing body of evidence showing that your neighbors and your neighborhood have a huge impact on our life prospects. Concentrated poverty amplifies all the negative problems of growing up poor because you attend schools with fewer resources, weaker parental and community support, and thinner social networks. A new study points up a subtle, second-order problem associated with poor neighborhoods. Parents decide how much effort to invest in helping their kids study (helping with homework, seeking tutoring, pursuing other learning activities) based on how well they think their kids are doing in school. In poorer neighborhoods with generally lower-performing schools, parents compare their children to peers who may be performing below average, leading them to mistakenly conclude that their children are performing well academically, and leading them to under-invest (their time and energy) in promoting academic performance.

Must Read

1. The cure for costly housing is more costly housing. Bloomberg columnist Noah Smith perplexes his non-economist friends in San Francisco with the highly counter-intuitive claim that the solution to the city’s exploding affordability crisis is building even greater numbers of expensive homes. It’s an article of faith among housing activists in that city, and elsewhere, that the only just solution for housing affordability is building more deeply subsidized apartments. For Smith–as for us–the problem boils down to demand and supply: the demand for opportunities to give in great urban spaces (like San Francisco) has grown much faster than the supply of housing there, and given a shortage, higher income residents can out-bid middle- and lower-income residents for market housing. The only solution is to expand supply, and the fragmentary evidence from San Francisco is that the modest increase in construction achieved in the past few years has already had the effect of moderating rent increases. The nation’s housing affordability problems are a teachable moment for economists, and in his usually thoughtful and dis-arming way, Smith has shown how this works.

2. Rents are falling in New York City. Meanwhile, from his perch on the East Coast, Slate’s Henry Grabar offers up a small, but growing collection of anecdotes about declining rents in New York City. Increasingly, developers are offering prospective renters concessions (usually a month or two of free rent), and for some units, prices are actually lower now than a year or two ago. One source estimates that more than a quarter of new apartments are offering concessions. Grabar thinks this may be the harbinger of further easing in rental rates, as tens of thousands of new apartments are in the construction pipeline in New York. As they come on the market, landlords will be forced to offer better deals to land tenants. The evidence here is still partial and preliminary, and even though it doesn’t signal a reversal of the rent hikes seen in the past five years, it does show that as supply catches up to demand, price increases abate.

New Knowledge

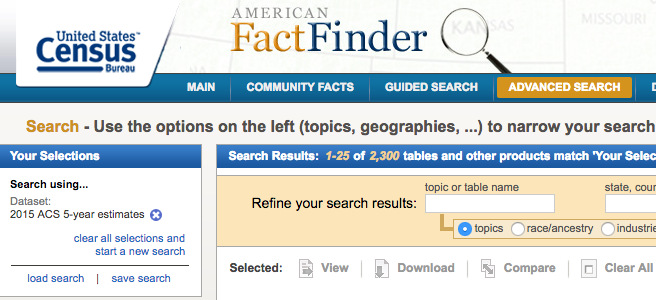

1. The 2011-15 five year ACS data. For data geeks, Christmas comes fairly early in December. This year it fell on December 8th, the date that the Census Bureau released its tabulation of the five-year 2011-15 American Community Survey. The ACS is our primary tool for understanding key changes in demographics, household well-being, housing and a wide range of other subjects. The Census aggregates five years of data to produce geographically fine-grained estimates of population and housing characteristics. You can learn more at the Census website, and can download data for particular geographies using American Fact Finder. Already, scholars and statisticians are beavering away at the new data: expect all manner of new studies and pronouncements based on this treasure trove. And remember one other thing: the ACS is a tangible and quite valuable product that is produced courtesy of the federal government and your tax dollars. Without the ACS–and there are real threats to is continuing existence–our nation would be flying blind when it comes to many important trends and issues. So be sure to use it, and if you find it valuable, let your elected representatives know.

2. America’s metropolitan neighborhoods are becoming more diverse–gradually. One of the first sets of findings from just released ACS data is an examination of the racial and ethnic composition of US neighborhoods and metropolitan areas by the Brookings Institution’s Bill Frey. In the aggregate, US metropolitan areas are growing steadily more diverse: Among the 100 largest metro areas, the share of the population that was non-Hispanic white declined from 64 percent in 2000 to 56 percent in 2011-15. Latinos increased from 15 percent to 20 percent of metro residents, and Asians from 5 percent to 7 percent. Blacks were about 14 percent of metro residents in both years. The typical white resident lives in a neighborhood that is less diverse than the overall metropolitan area. Even so, the typical white resident now lives in a neighborhood that is noticeably more diverse than it was in 2000. Among the 100 largest metro areas, the typical white resident lived in a neighborhood that was 79 percent white in 2000 and about 72 percent white today. Frey’s article in the Brookings blog “The Avenue” has data for the 100 largest US metro areas.