What City Observatory did this week

1. How we measure segregation depends on why we care. Daniel Hertz explores the various ways we measure the geographic separation of different racial and ethnic groups. There’s a widely used dissimilarity index, that looks at differences between two groups, like blacks and whites. There are broader measures that look at population diversity. The different measures tell us about different aspects of segregation, and remind us that segregation is not a simple, one-dimensional problem.

2. The cliff notes version of The New Urban Crisis. Urbanists everywhere are reading and talking about Richard Florida’s latest opus exploring what he calls “The New Urban Crisis.” Has he re-canted the creative class message? What problems are inherent to 21st century urbanism, and which can be solved? And who can solve them? To get you started, we offer a short outline of the book. In the coming weeks, we’ll have more to say about what’s in the book. Be ready for the discussion.

3. Why is affordable housing so unaffordable? Cities and states are struggling to come up with more money to help build additional affordable housing, but they’re finding their money doesn’t go very far. Unit costs of constructing new apartments in San Francisco, for example, are in the $600,000 to $800,000 range, and even more modestly priced metropolitan areas like Portland and Minneapolis are not able to build many units because of high costs. Private builders have come forward in Portland with offers to build more spartan units for as little as $100,000 each, and there are proposals to adopt pre-fab, off-site construction techniques, but until something radical happens, the high cost of construction will be a big barrier to the public sector building enough units to make a serious dent in the housing affordability problem.

4. Happy Earth Day, Oregon! Let’s widen a freeway! Saturday April 22 is the 47th installment of Earth Day, and if the rate of climate change is any indication, not a sign that we’ve made much progress. Some places, like Oregon, have legislated bold goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions . . . a few decades from now. In the mean time, the highway lobby has its own plans for celebration: a billion dollars worth of freeway-widening projects in the Portland area. Its doubly ironic that a city that made national headlines for tearing out a downtown freeway when environmentalism was new four decades ago, has somehow forgotten that building more freeways just generates more traffic and pollution.

Must read

1. Will Boomers age in place? Day-by-day, the baby boom generation is getting older. While housing market experts have long maintained that boomers will want to “age in place,” declining health, changing preferences and shifting real estate markets are all likely to impact those decisions. As has regularly been the case over the decades, the sheer numbers of boomers simultaneously lurching into and out of markets as changed whole industries. As boomers look to sell their mostly suburban, single family homes, there’s the danger there’ll be a huge glut on the market, just as demand by younger generations has shifted back towards cities. The result, the University of Utah’s Art Nelson suggests, is likely to be the case that many boomers will be “stuck in place” by the low value of their homes.

2. The high cost of negotiated community benefit agreements. Social justice advocates have increasingly turned to negotiating formal “community benefit agreements” (CBAs) to assure that when new developments go forward, that those impacted by growth are change are compensated. In Oakland, California, developers on one apartment complex signed aCBA worth nearly $800,000 on a 400 unit apartment project; another apartment agreed to a $1.8 million CBA. In both cases, the money went to a range of investments in the nearby community and contributions to local non-profits. And these amounts were on top of development impact fees that the City already imposed. SPUR’s Robert Ogilivie looks at the downside of CBAs: the delay and uncertainty associated with the negotiation of a community benefit agreement makes it hard for developers (and prospective tenants) to know in advance whether the decision to choose a particular location will be cost-effective, or even possible.

3. Tesla’s parking problem. How’s Elon Musk going to solve urban transportation problems, either with his sleek Tesla vehicles, his swoopy Hyper-Loop or magically inexpensive highway tunnels, if he can’t even figure out how to solve the parking problem at his own offices? That’s the question that’s posed by an article in the Wall Street Journal chronicling the crazy competition for parking spaces at Telsa HQ. Streetsblog Angie Schmidt has the details, in a post entitled “Tesla’s Parking problem says a lot about Elon Musk’s particular brand of tech saviorism.” Our advice: have Elon read Don Shoup’s High Cost of Free Parking. He might also pay attention to what his colleagues at Uber and Lyft are saying about the need for road pricing.

New ideas

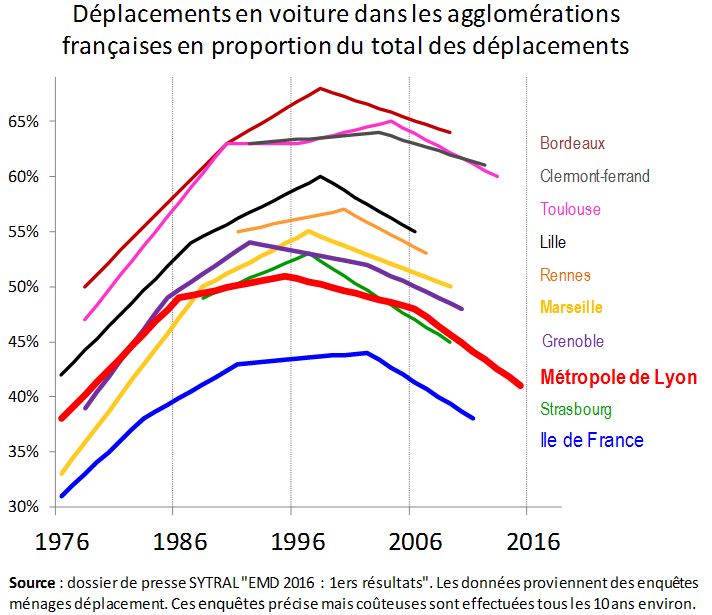

Peak Voiture? Data from France shows that car travel in its largest metro areas actually peaked about 15 years ago, and has been declining everywhere since then. The following data show car trips as a percentage all trips in the country’s principal urban areas. (Ile de France is the Paris metropolitan area). A tip of the chapeau to Rue 89Lyon which presented these numbers in an excellent story relating how down-grading the autoroute through Lyon to a boulevard will actually facilitate travel and improve urban life.

City Observatory in the news

Joe Cortright is interviewed about Detroit’s rebound, and how to cope with concerns about gentrification in the Center for Michigan’s monthly magazine “Bridge“.

A New York Magazine “Science of Us” feature asks “Is everyone focusing too much on gentrification?” The story quotes City Observatory’s Joe Cortright and our study “Lost in Place” looking at the persistence and growth of high poverty neighborhoods in the nation’s largest metropolitan areas.