What City Observatory did this week

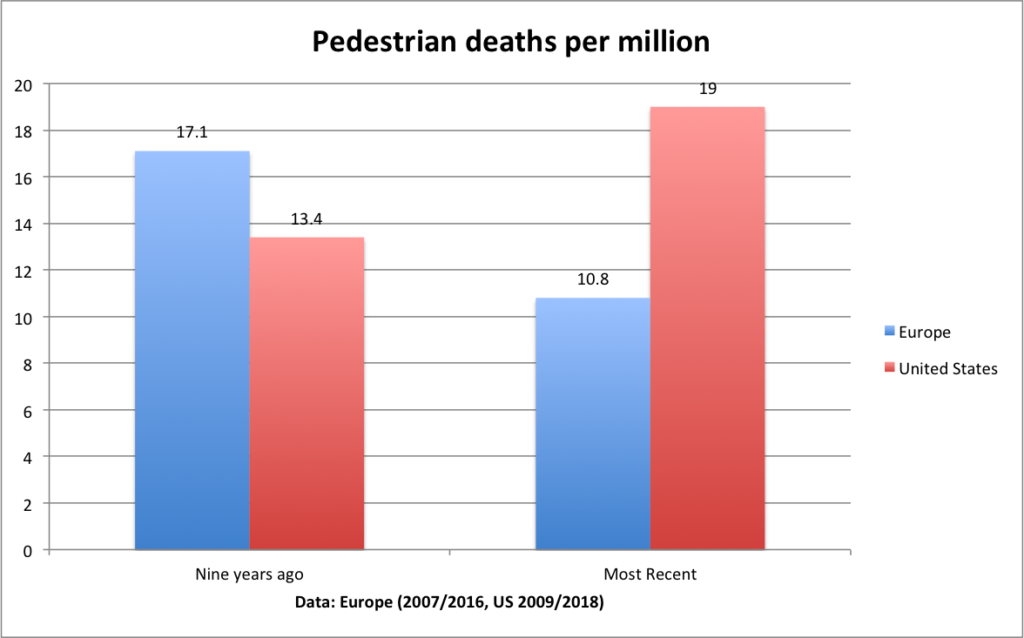

1. Why is the US killing so many pedestrians? The grim data from 2018 are now available: More than 6,200 US pedestrians were killed by automobiles last year, an increase of more than 50 percent in the past decade. Many reasons are given to explain the trend, and some make it sound as if pedestrian deaths are inevitable in a modern country with cars and distracted drivers. Meanwhile, the evidence from Europe shows that highly developed economies–ones with lots of cars and universal smart phone ownership–can have low and declining rates of pedestrian fatalities. Indeed, in the past nine years for which data are available, European pedestrian death rates have fallen by more than a third. Even though Europeans walk far more often, and on narrower streets that regularly mix cars and pedestrians, the pedestrian death rate in the US is now 75 percent higher than in Europe. In the US, we’re a long way from Vision Zero, and we’re heading in the wrong direction.

2. Valuing Walkability. A new report from Smart Growth America and George Washington University looks at the real estate value associated with walkable urban neighborhoods. The study reports that more walkable neighborhoods in US cities command substantial market premiums over less walkable places, and that this premium has increased in recent years. The growing value attached to walkable, urban places is evidence of what we’ve called the “Dow of Cities”–a market signal that urban living is both valuable and in short supply.

Must read

1. Google pumps a billion dollars into Bay Area housing affordability. Google CEO Sundar Pichai published a blog post announcing Google’s intention to devote a billion dollars to addressing housing affordability in the San Francisco Bay Area. It’s a testament to the severity of the housing shortage to the economic vitality of the region, that the company would make such a large commitment. It’s also a reminder of the scale of the problem. Three-quarters of the Google commitment is in the form of the company’s plan to seek to get housing built on land it owns which is apparently now designated for commercial or industrial use. The company says this $750 million in property, could support 15,000 houses, meaning the land alone is worth $50,000 per housing unit.

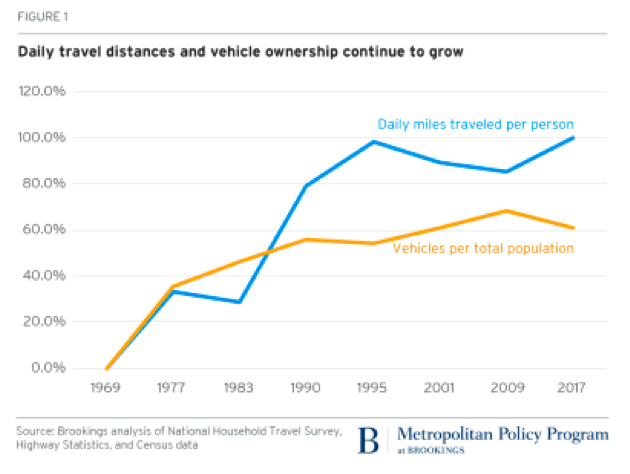

2. Brookings connects the dots on transportation, accessibility and urbanism. A new essay “Connecting people by proximity: A better way to plan metro areas” by Adie Tomer, Joseph Kane and Lara Fishbane of Brooking’s Metropolitan Policy Program, makes a strong case that cities need to shift the focus of policy from moving people (and things) to building the kinds of places people want to be. For too long, they argue, we’ve optimized cities to increase travel speed, chiefly by car, to enable people to more easily connect to one another. That’s simply generated decentralization and sprawl, and ended up increasing the amount of travel we all have to undertake.

Instead, they argue, we should be looking to improve the accessibility and connectedness of cities by designing land use patterns–and promoting density–in a way that minimizes the need to travel.

Instead, they argue, we should be looking to improve the accessibility and connectedness of cities by designing land use patterns–and promoting density–in a way that minimizes the need to travel.

3. The kids are alright. The older generation may have trouble spotting the connection between spending billions of dollars to widen freeways and taking the challenge of climate change seriously, but the young do not. BikePortland reports that SunrisePDX, the local affiliate of the national climate action network has made blocking construction of new freeway lanes in Portland one of their signal priorities, along with fighting an export terminal for fracked crude oil. The group marched on City Hall in Portland last week, taking their campaign to the office of Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler.

Their letter to the Mayor makes an eloquent case for a change of direction.

It is far past time for words without meaningful action. We are tired of hearing about “environmental protection” in the abstract, while new projects are being built to facilitate the continued expansion of fossil fuel usage. The time is now to act boldly; to break cleanly from the status quo; to take the political risks necessary to secure the future of our planet and its inhabitants.

New Knowledge

Excessive land use regulations increase vacancy and produce longer commutes. We’ve long understood that strict local controls on new development can drive up the price of housing. A new study from England shows that development restrictions can have other negative effects as well. The study by Paul Cheshire and colleagues from the London School of Economics looks at the connection between development restrictions in English local planning areas and variations in local vacancy rates and commuting distances.

The theoretical effect of development restrictions on vacancy is ambiguous. By driving up prices, restrictions essentially raise the cost of leaving a unit vacant, and thereby encourage sellers to sell more quickly. But at the same time development restrictions may tend to amplify the mismatch between the characteristics that buyers are seeking and what’s actually available in the market. If it’s harder to build new units that match what people are looking for, they have search longer to find what they want and to make due with something that’s less that optimal. The study finds that this “mismatch” effect dominates, and that a one standard deviation increase in the strictness of local planning requirements leads to a 0.9 percentage point (23 percent) increase in vacancy rates. Also, because buyers have to look further afield for a home that matches their needs, they tend to end up commuting farther to work. The author’s estimate that the increase in development strictness by one standard deviation increases commuting distances 6.1 percent (which is in essence an additional, but generally unrecognized, increase in the cost of housing, as workers have to spend more time and money to live where they want).

Cheshire, Paul and Hilber, Christian A.L. and Koster, Hans R.A. (2018) Empty homes, longer commutes: the unintended consequences of more restrictive local planning. Journal of Public Economics, 158. pp. 126-151. ISSN 0047-2727

In the News

In Governing, Alan Ehrenhalt quotes City Observatory’s Gentrification A to Z commentary in is column “The fables of gentrification.” Ehrenhalt writes: “Far more urban change is being created by poorer people and immigrants moving to suburbs than by rich people moving downtown. And actual displacement — the popular notion of wealthier white newcomers forcing out long-term minority residents — is even more rare.”