What City Observatory did this week

1. Scooters are a success in Portland, but there’s an insidious double standard. A new report from Portland’s Bureau of Transportation details the success of the city’s 120-day long experiment allowing about 2,000 scooters from Bird, Lime and Skip to be operated on city streets. The report judges the scooters against a number of tough standards and finds they provided over 700,000 trips, that nearly a third of Portlanders tried them, and they led to reduced car travel, and were most heavily used in the evening peak hour, when the city most needs alternatives. It’s a positive report, but it begs a much larger question: Why aren’t the same questions and tests being applied to letting cars run rampant on city streets? We notice, for example, that the city charges scooter users more than 20 cents a mile for their trips, about ten times what car users are asked to pay in state and local gas taxes. And if the city can strictly limit the number of scooters allowed, and require operators to install electronic governors to limit their speed in the name of safety, why isn’t it doing the same thing with two ton automobiles? We’re looking forward to PBOTs next report applying these same tough standards to the city’s obviously failing 110-year experiment with cars.

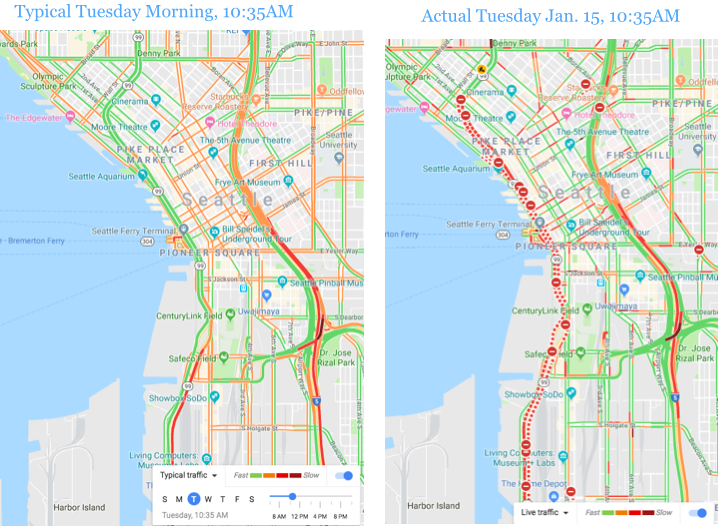

2. Carmaggedon never comes (Seattle edition). Seattle just closed it’s decrepit Alaskan Way Viaduct, an ugly double decker freeway that separates the city’s downtown from Elliott Bay. Losing the roadway means that more than 90,000 vehicles will have to travel somewhere else, and has led to predictions of “carmaggedon” in the Emerald City–at least until a new $3 billion highway tunnel opens sometime next month). We take a look at the first few days of traffic without the viaduct, and find, surprisingly to some, that downtown traffic in Seattle is not only no worse than usual–in many spots it’s actually better. It’s yet another example of “reduced demand”–taking away road capacity leads to a reduction in total vehicle traffic in an area. This is a kind of mirror image of the well documented phenomenon of “induced demand” in which newly build roadways rapidly fill to capacity. It’s also an object lesson in why we need to revise our outdated mental models that tend to treat traffic as a fixed, irreducible quantity. Cities can quickly adjust to lower levels of road capacity, with beneficial results.

3. Why the Columbia River Crossing will remain dead. In the past few months, there have been a stirring of efforts to revive the proposed Columbia River Crossing, a 3 plus billion dollar freeway widening project connecting Portland Oregon and Vancouver Washington. The original proposal never made much sense, and the deal foundered over disagreements between Oregon and Washington on whether the project should include a short light rail extension. Despite continued frustration with traffic on the route, it is still apparent that there’s no agreement on the fundamental issues here, which in addition to the fact that neither of the state’s currently has any money for such a project, means that its likely to stay dead for a good time longer. The acceptability of light rail in Vancouver is still a deal-breaker: Washington Governor Jay Inslee says the project must include rail; local Republican lawmakers and the city’s daily paper insist it can’t or must be balanced with two or three new highway bridges.

Must read

1. A Green New Deal has to address land use. The newly elected House Democratic majority is making waves with a proposal for a kind of “Green New Deal” that would make big investments in de-carbonizing the US economy while creating lots of jobs. That’s a worthwhile policy objective, but as proposed this “deal” has been short on re-thinking how we re-build our communities to support the kinds of low-carbon living that are impossible in our sprawling, car-dependent communities. The Brookings Institution’s Jenny Schuetz has some friendly amendments to offer to those pushing for a Green New Deal that spell out how we can address these issues, as well as promoting housing affordability, and addressing the shortage of cities. As she says: “The Green New Deal should set clear benchmarks for environmentally sound land use, provide financial assistance to offset compliance costs for lower-income households and communities, and enforce penalties from localities that do not improve.”

2. Congestion pricing advances in Los Angeles. Metro, the transit operator for Los Angeles is hinting that it will propose some form of congestion pricing to tackle that city’s perennial traffic problems, according to Curbed. The plan would provide incentives to reduce car travel at peak hours and also provide funding to support expansion of transit, a key part of the city’s 2028 Olympic plans. It’s especially good news that the effort is benefitting from the advice of UCLA’s Michael Manville, who’s carefully studied congestion pricing around the world, and has a wealth of ideas on how to employ it successfully. For example, Manville is urging the city to use some of the revenue from congestion pricing to reduce impacts on low income drivers.

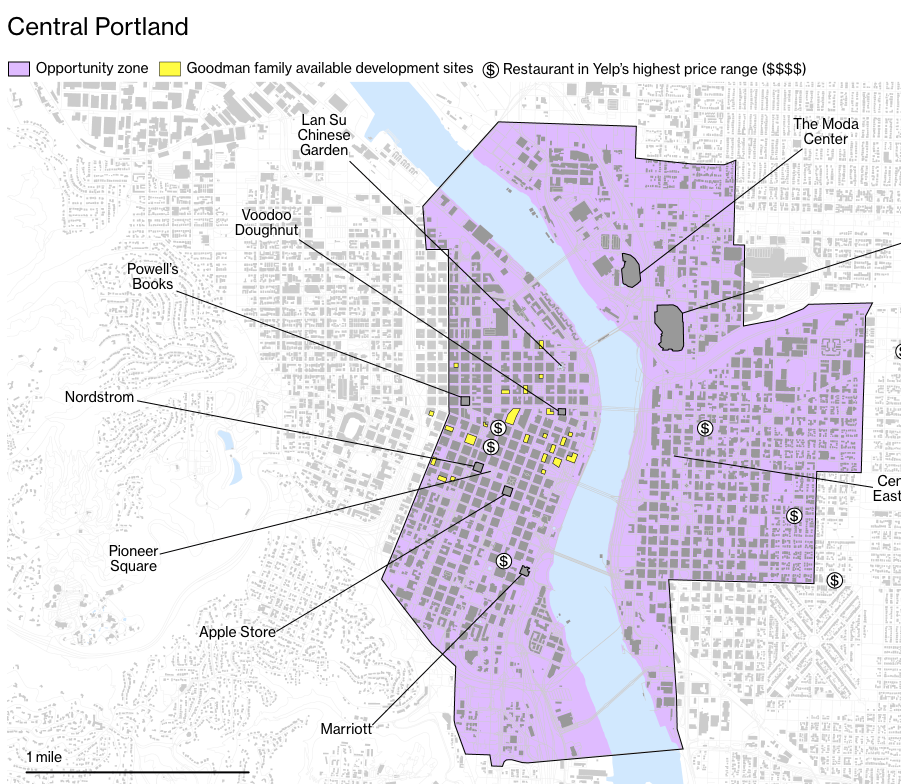

3. All of thriving downtown Portland is an opportunity zone. In an article entitled “Welcome to Taxbreaklandia,” Bloomberg Business Week has a compelling close-up look at one of the most problematic aspects of the new opportunity zone tax break. All of downtown Portland–an area that is doing quite well in terms of job and investment growth–has been designated as an opportunity zone. Lots of investment that would have undoubtedly happened anyway will qualify for generous capital gains tax breaks. Downtown neighborhoods qualify because a significant fraction of residents live below the poverty line. There’s a disconnect between the Opportunity Zone’s simplistic theory of change (i.e. people are poor because there aren’t jobs and investments near where they live) and the incentives that state and local governments (and private investors) have to make maximum use of the federal tax break. There are 8,700 opportunity zones nationally. With so many eligible places, including ones that are already great investment locations offering this tax break there’s precious little incentive for investors to look seriously at marginal or troubled locations. Opportunity zone tax breaks may end up mostly rewarding investors for things they (or others) would have done anyhow, costing the federal government billions, while doing little or nothing to address the plight of the poor.

4. We can’t address climate change without reducing car use. The Transit Center’s Steve Higashide has a commentary at The Hill emphasizing an important point: technology alone, say in the form of vehicle electrification won’t be enough to get the kind of carbon reductions we need fast enough to advert a climate crisis. In the transportation realm, the political compromise between the highway lobby and transit advocates is a kind of pie-splitting multi-modalism. But that just tends to perpetuate policies that lead to increased driving and emissions. As Higashide argues, “an ‘all-of-the-above’ approach to surface transportation doesn’t cut it. It’s not enough to build more transit, as long as federal policy continues to subsidize the highway-and-sprawl machine.”

New Knowledge

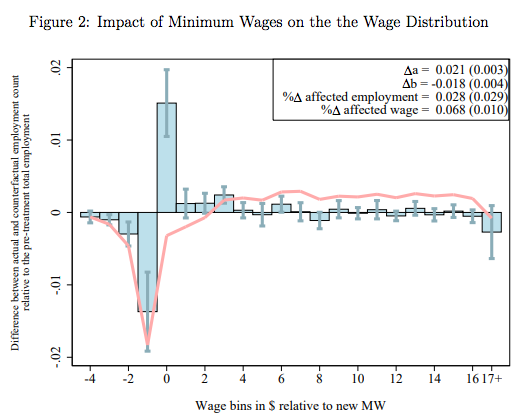

Higher Minimum wages don’t reduce employment. One of the perennial issues in economic policy is whether higher minimum wages can be an effective tool to fight poverty. One common objection is that higher wages will lead employers to reduce employment. A new study from four four economists looks at this question using a new statistical technique, called a bunching estimator, that looks at the distribution of the number of jobs right around the level of the minimum wage. The study compares the number of jobs just below the new minimum wage before the minimum wage is increased with the number of jobs just above the minimum wage after the increasing. Using data from 138 instances in which minimum wages were increased, they find no net impact on employment, i.e. the decrease in the number of jobs just below the threshhold balances almost exactly the increase in jobs above the threshhold. The following chart summarizes their results: the blue columns show changes in employment levels at each point above and below the new minimum wage; the red line shows the cumulative change in employment measured from the lowest paid jobs to the highest.

The authors conclude that, especially at the relatively low levels of the minimum wage in most states and cities, negative employment effects haven’t been felt.

Doruk Cengiz, Arindrajit Dube, Attila Lindner and Ben Zipperer The effect of minimum wages on low-wage jobs: Evidence from the United States using a bunching estimator. NBER Working Paper 25434, http://www.nber.org/papers/w25434

In the News

Brookings Institution’s Jennifer Vey has a thoughtful column on the value and importance of transformative placemaking. She challenges those who automatically conflate any effort to improve neighborhood livability with gentrification, citing Jason Segedy’s City Observatory commentary on the growing meaninglessness of that overused term.