What City Observatory did this week

It’s time to get serious about climate change. We published a guest commentary from City Observatory friend Ethan Seltzer, who takes a critical look at the largely rhetorical approach that the Portland region is taking to the increasing serious menace that is climate change. Globally, the International Panel on Climate Change is warning that time is drawing short to make meaningful progress in reducing carbon emissions. Locally, Oregon’s own Greenhouse Gas Commission reports that the state is losing ground in its efforts to reduce GHGs, almost entirely because of an increase in driving in the past few years. As Seltzer writes, what Oregon needs is not a just a low carbon future, but a low car future.

Must read

1. An affordable housing crisis for whomst? Allan Mallach, author of one of our favorite books of 2018, The Divided City, has a new article at Shelterforce exploring the variations in housing affordability across US metro areas. He points out the affordability per se is not the problem in many declining rustbelt neighborhoods: there, the key problem is that low income families don’t have enough income to afford housing. Even though housing values are low in these markets, Mallach explains why private landlords find it difficult to charge rents affordable to the lowest income families:

While house sale prices will keep going down nearly to zero until they reach their market level—if there is one—rentals work differently. Landlords have to factor in how much they need for maintenance, reserves, repairs, taxes, and some combination of mortgage payments and an acceptable return on the value of their equity. Landlords also factor in their expectations. If they think their property is appreciating, they’ll accept a lower annual rate of return on equity, because they figure they’ll make up for it when they sell the property. But if they think it’s losing value, they’ll look for a higher annual rate of return to make up for the fact that they may not get their money back if they try to sell it down the road. The lower their expectations are, the more they will try to increase their net cash flow, cutting back on maintenance, and even not paying property taxes. So even a landlord who owns a house worth $0 on the market may still need to rent it for $700 to cover their costs and get a sufficient return.

If a landlord can’t get the minimum rent they feel they need to make ends meet, they are not likely to lower the rent below that level, which would mean knowingly losing money. Instead, they’re more likely to walk away.

In these markets, building more subsidized affordable housing, through a combination of Low Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC), and Section 8 Housing Choice Vouchers may help some families get into better housing, but can easily lead to the abandonment of other market-provided housing.

Moreover, most LIHTC projects are built in high-poverty neighborhoods, areas where sites are available and more CDCs are active, but where total housing demand is not growing. As a result, those projects often cannibalize the existing housing stock; in other words, as new LIHTC units come on line, most of their tenants come from existing rental housing in the same (or similar) neighborhoods, often bringing Housing Choice Vouchers with them. They move out of private market units, or older LIHTC projects, in to areas that already have a large surplus of housing, putting even more units at risk of abandonment.

2. Housing and transport from a Japanese perspective. Japan has some of the world’s highest housing density, wide-ranging inter-city rail systems and urban transit, and surprisingly affordable housing. How do they do it? In an essay at Medium, Brendan Hare explores some of the key aspects of the Japanese system. For one thing, land use regulation is very different: in areas designated for residential development, it’s generally just as easy to build apartments as single family homes. One practical result: Japan’s private railway companies have managed to finance their expansion, largely without public subsidy, by developing high density housing near train stations. And then there are web of other complementary policies: as has widely been reported, you can’t legally register a car in Japan unless you can show that you’ve got an off-street parking space in which to store it. Think of it as a “housing requirement for cars” rather than a “parking requirement for houses,” which is what we do in this country. It’s an informative look at how different institutional arrangements can produce much different and in many respects better outcomes than we experience in the US.

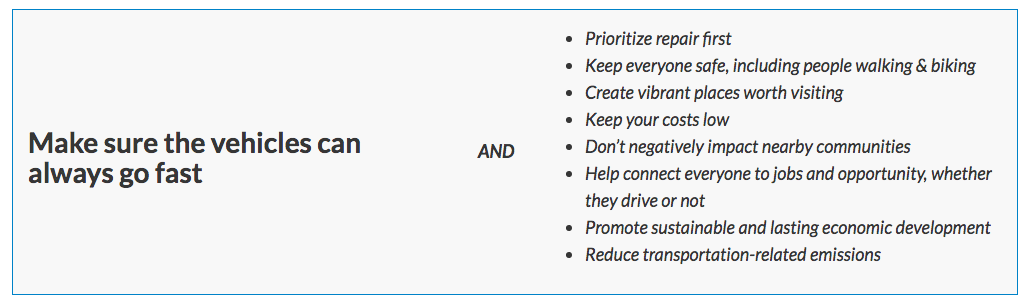

3. Speed kills, and highway engineers are all about speed. In her article, “How a singular focus on speed leads state DOTs to overspend and overbuild,” Smart Growth America’s Beth Osborne has a close look at the fundamental contradiction between the primary motivation of almost every highway engineering decision–making cars move faster–and virtually everything else we want our transportation system to accomplish. Whether its promoting safety, making urban environments more desirable, better connecting land uses, facilitating walking and cycling, encouraging transit or reducing energy consumption, giving priority to faster car trips generally makes things worse. Osborne shows that the focus on speed also drives state highway departments to choose expensive, inefficient projects that do little to make the transportation system work well for everyone. As she says, “It’s nearly impossible to square the priority of speed with most other state goals”

And we’ll add: the constant struggle to square the deeply ingrained philosophy of “faster, faster, faster” with conflicting policy objectives produces a rich array of convoluted public relations gimmicks, as state DOTs pay hard cash for faster roads, but mostly pay only lip service to other policy objectives.

New Knowledge

Effects of Age-based property tax exemptions. One of the favored classes, when it comes to property taxation, are older households. The stereotype is that older households are often poor and on fixed incomes and should be insulated from the burden of property tax payments, or tax increases or both. The difficulty with the stereotype, is that while some elderly households are poor, older people generally, and older homeowners as a group are now noticeably wealthier than other households. A new paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research examines the impacts of age-based property tax exemptions on homeownership behavior. It finds that the tax exemption is associated with higher rates of housing consumption by elderly households. Over time, older homeowners have gone from owning houses that were on average smaller, and lower valued than younger homeowners, to owning houses that are larger and more valuable than younger homeowners. The analysis suggests that the presence of exemptions leads older households to own homes longer–which is part of the intended policy effect. But with more older homeowners, fewer homes come on the market to be purchased by younger homeowners. In applying their modeled findings to Cobb County, Georgia, just outside Atlanta, the author’s estimate that the tax exemption led to an addition 7,600 to 11,700 senior households continuing to own homes in the County, with correspondingly lower numbers of younger households and fewer seniors renting their homes.

H. Spencer Banzhaf Ryan Mickey Carlianne E. Patrick, Age-based Property Tax Exemptions, Working Paper 25468

In the News

The Seattle Times featured Joe Cortright’s analysis of flaws in the Inrix congestion rankings.

The Portland Oregonian cited Joe Cortright’s critique of the Inrix data in its story on city congestion rankings.

Cortright said the report’s economic impact data points are “fiction.” “There’s no feasible set of investments that would let everyone drive as fast at rush hour as at 2 a.m., and the cost of building that much capacity would be far more than the supposed ‘cost’ of congestion.”