What City Observatory did this week

Copenhagen’s success: More than just bike lanes. Copenhagen is one of the world’s great cycling cities, and its accomplishments are a a beacon to those looking to build more bike friendly places. Most commuters in the city now travel by bike on a daily basis. Part of the city’s success stems from significant investment in bike infrastructure. While that’s critical, many Copenhagen boosters overlook some of the other significant aspects of Danish policy. Notably, Danes pay a 100 percent tax on new vehicles (essentially doubling the price of new cars), and also pay hefty taxes on motor fuel. In addition, the city is zoned for a much higher level of density that US cities, and invests heavily in affordable housing: nearly 20 percent of Danes live in some form of social housing. Making dense urban living abundant and affordable, and asking cars to pay something closer to their full social and environmental costs is also essential to promoting cycling.

Must read

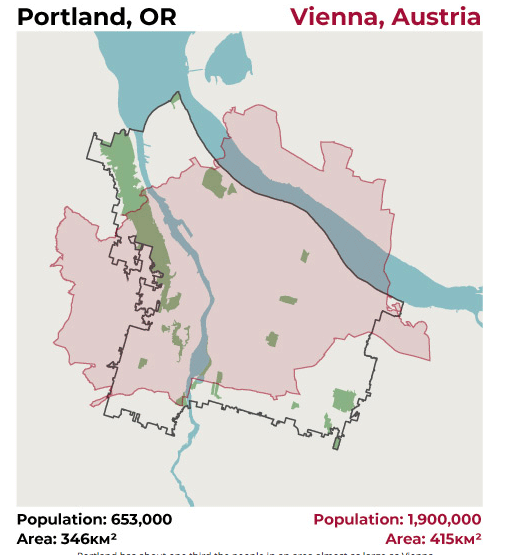

1. Green cities are dense cities. Sightline’s Alan Durning has a provocative comparison of the density levels in three Pacific Northwest cities (Vancouver, Seattle and Portland) and some similar sized European cities (Paris, Vienna and Barcelona). The European cities are, not surprisingly vastly denser (even though all three have notably large public greenspaces). This becomes clear when you overlay the municipal boundaries of the pairs of cities. Here’s Portland compared to Vienna; Vienna has three times as many people in a slightly larger space.

As Durning writes, higher density translates directly into a greener place.

Paris is almost six times as densely settled as Seattle. Barcelona is three times as dense as Vancouver. And Vienna is more than twice as dense as Portland . . . Compact, populous cities save so much energy by sharing walls, shortening trips, and shedding cars that they are to urban planning what windmills are to the electric grid: indispensable climate protectors.

It’s also worth noting that because all these cities do a better job of enabling the construction of dense new housing (and here, Vienna is an exemplar), they are relatively more affordable than the American cities, which still make it difficult or impossible to build anything other than single family homes in much or most of their territory (although that’s changing with just passed planning laws).

2. Housing policy advice for Salt Lake City. The Marron Institute’s Brandon Fuller, writing in the Salt Lake Tribune, offers his views on how to address that city’s growing housing affordability challenges. Based on his review of the research in the field, Fuller has a series of do’s and don’ts: On the do list, is expanding housing supply, including ADUs and SROs (accessory dwelling units and single room occupancy housing). Legalizing these forms of housing can make a material difference in housing availability and affordability for low income populations and have a minimal urban footprint. Also on the “do” list: use a portion of Tax Increment Financing to subsidize affordable housing development (a Portland policy we’ve profiled at City Observatory). Top of the “Don’t” list: inclusionary housing requirements. As Fuller notes, while politically appealing, inclusionary housing requirements act like a tax on new housing supply, discouraging development and tending to tighten housing supply and, perversely, drive up market rents. While tailored for the current debates in Salt Lake City, we suspect this advice has equal merit in many other cities across the country.

3. Reflections on gentrification. New York Magazine‘s Intelligencer section has a thoughtful essay reflecting on the debates around gentrification in light of new research that’s come out in the past few months. Two of the most careful and comprehensive studies taken to date, by the Philadelphia Federal Reserve Bank and New York University researchers, show that there’s little, if any displacement from gentrifying neighborhoods.

Despite the evidence that the impacts are minimal, there’s still a strong opposition to gentrification, that generally manifests itself in trying to block any change. As the Intelligencer essay points out, this is often counterproductive. Measures that block new housing can drive up rents, and even set-aside policies that reserve affordable housing for neighborhood residents can simply reinforce patterns of segregation. Ultimately, policy has to acknowledge that neighborhoods will change, and give more thought to figuring out how to assure that the benefits of that change are widely shared:

Government should be making it easier, not harder, for people to change addresses if and when they want to. As newcomers roll in, with or without college educations, nobody has the right to tell them they shouldn’t or can’t. In the short term, gentrification makes neighborhoods more, not less, economically diverse and more racially integrated. The problem is that over time, those advantages dissipate, though not uniformly, and temporarily mixed neighborhoods become homogeneous again, and each new population in turn defends the turf it colonized. Diversity, not preservation, should be the goal. Instead of expending vast amounts of energy trying to shield fragile communities from change, we should make sure they reap its benefits.

In the news

Writing in the East Oregonian, Kevin Fraser cites City Observatory’s analysis of four-decade changes in neighborhood demographics in the nation’s 50 largest metropolitan areas.