This year, William Fischel, a professor at Dartmouth and one of the country’s leading scholars of land use policy, published a new opus on zoning: Zoning Rules! There’s far too much in the book to do a comprehensive review, but we’re going to pick out some of the most interesting and important arguments for posts over the next week or so.

The chapter with perhaps the broadest interest answers a basic question: How did we get here? While many people who follow urban issues, especially housing, are familiar with some of the basic arguments about how zoning acts as an exclusionary policy that keeps home prices higher than they ought to be, few are familiar with where these issues came from, and why they have become so much more prominent in recent years.

Fischel describes the evolution of land use law from a series of somewhat ad hoc regulations imposed by people with mixed interests in neighborhood development, to the creation of zoning and all-residential suburban neighborhoods protecting themselves against residential “overdevelopment” and industry in the 1920s and 30s, and finally the land use revolution of the 1970s, in which the growing financial importance of homeownership and new powers to stymie developments changed “exclusionary zoning” from something that happened on the level of the municipality to something that happened on the level of the metropolitan area—with wealthy coastal regions beginning to pull away from the rest of the country in their cost of living.

Instead of simply summarizing Fischel’s narrative, we’ve turned it into a “zoning parable,” following one (long-lived) shopkeeper as he experiences (and takes advantage of) the twists and turns of local land use controls. This parable is meant only to reflect Fischel’s arguments—we’ll comment on and critique them in a follow-up post.

You’re a 20-year-old shopkeeper. It’s 1900. You live close to the middle of a large American city, in an apartment above your shop. The city is growing rapidly, and new apartments are going up all around your neighborhood, replacing smaller two-flats and single family homes. It’s a lot of change, and you remember when you were a child and the neighborhood was quieter, when there were more yards—but you also can’t help but notice that every time a new development is completed, the stream of customers to your shop gets a little bit bigger, and your cash register gets a little fuller. So you don’t complain.

A few years later, you move out to one of the new bungalow subdivisions in a newly-incorporated suburb just outside of town. You take a streetcar to work, so you can separate your life between the quiet of your residential neighborhood and the busy, densely-packed district that keeps business steady at your shop. But you notice almost immediately that they’re starting to build city-like apartments near the streetcar stops; within a year or two, a stretch of blocks that were all single-story single family homes, or even empty fields, are converted into a newer version of the neighborhood you left.

As the community grows, your tiny municipality’s ability to provide basic services is strained. It seems like the best solution is to accept annexation into the center city—just like your old city neighborhood had once been a suburb, and was swallowed up by the metropolis as it developed.

Several years later, your business is doing so well that you can afford to buy one of those newfangled cars. With the car, you move out beyond the city limits again—but this time, you don’t move next to a streetcar line. You know that that’s where developers build apartments. You move a mile or so away, to another new subdivision, from which you can drive to work. When the streetcar company requests permission to build a new line near your house, you and your neighbors organize to stop it, and keep away the apartments and density you know would come along with it.

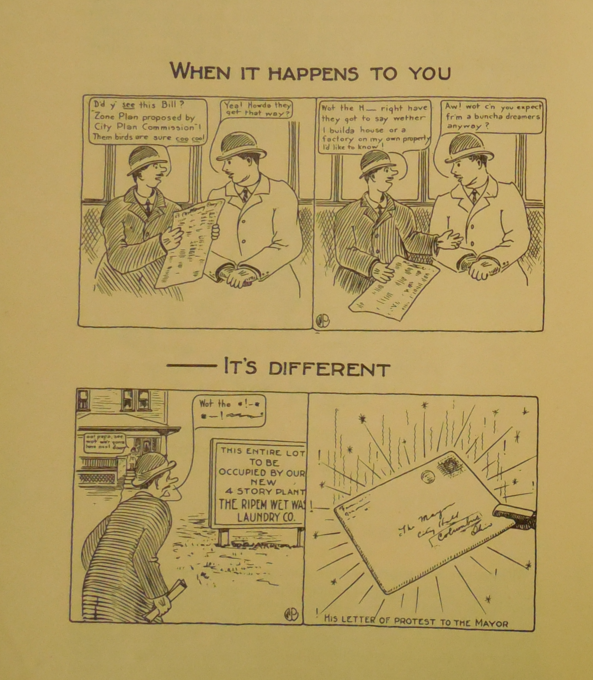

But overnight, it seems, trucks begin appearing on the streets around your neighborhood. Businesses, freed from the need to locate along rail lines, have been building small factories and plants all over the suburban periphery. You’re not just worried about the noise and pollution—you’ve invested quite a bit of your savings into your new house, and you’re concerned that new businesses might affect your property value. Plus, you don’t live anywhere near your shop now, and you’ve got nothing to gain from new development that might bring more people to the area.

Fortunately, there’s a new legal mechanism your neighbors and city leaders are talking about: zoning. With zoning, you can make it illegal to build industry anywhere near your residential neighborhood. You can also make sure that no one builds apartments on your block of bungalows, which you worry might cast some shadows, add too much traffic, and reduce the value of your home.

Since growth in your community is now capped, when representatives from the big city come along asking about annexation, you’ve got no good reason to say yes. You don’t need their help with services, and you’d like to maintain control over the zoning process locally. Your community will stay a suburb.

This state of affairs works for a while. Jobs stay in the central city, and your suburban neighborhood remains mostly single-family residential, although it allows pockets of industry and apartments within certain districts. Some suburbs are even more restrictive, protecting their large homes on large lots; others are more open to development, according to their political balance and neighbor preferences.

But in the years after World War Two, things begin to shift. They start building highways from the suburbs to the city, which brings much more pressure for development. It seems way more people have cars now—including people who never would have been able to afford them before, people you might have wanted to stay in the city—and they start looking for housing outside in the suburbs. Traffic gets worse.

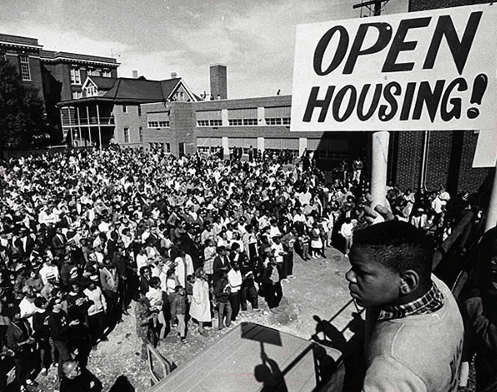

Over the coming decades, there are other issues, too. Civil rights organizations involved in the “open housing” movement begin talking about taking on suburban “exclusionary zoning”—places that use zoning in a discriminatory way to allow only high-end residential development, out of financial reach for most black households. It looks like only allowing high-end development might get you in trouble with the courts; some towns decide that not allowing any development is a safer course.

Moreover, over the course of your retirement, your home has made up a bigger and bigger part of your wealth—and the same is true of your neighbors. Although you don’t know it, this is a nationwide phenomenon: the proportion of household wealth owed to homeownership will increase by almost 50 percent from the 1960s to the end of the 1970s. That makes homeowners like you even more sensitive to any changes in the neighborhood that might affect the value of your largest investment.

At the same time as you and your neighbors have more reason than ever to be wary of neighborhood changes, there are new tools to help you exert control over those changes. You’ve heard of nearby towns using the National Environmental Policy Act, passed in 1970, to sue to stop development on environmental and conservation grounds. And the creation of a new regional planning body means that there are now at least two levels of government you can appeal to with the authority to stop development—and you just need one of them to agree with you to win.

This revolution in land use planning in the 1970s means that your metropolitan area no longer has a mix of pro- and anti-growth towns. Almost anywhere homeowners live, they’re demanding a stop to almost all development, worried about their massive investments in their homes—and most of the time, they have the ability to win.

But you’re not too worried about that. Sure, individual towns have been able to use zoning to keep their home prices high—that’s the whole point, right?—but there’s no way that could happen to an entire region. You can’t imagine a whole metropolitan area becoming so expensive that it forces people to move not just to a cheaper suburb, but a cheaper part of the country.

That probably won’t happen.