Yesterday, we critiqued a study that claimed to show that the benefits of putting low-income housing in very low-income neighborhoods greatly exceeded the benefits of putting it in higher-income neighborhoods—especially higher-income and predominantly white neighborhoods—where it might have more of a pro-integration effect.

Among the several points of our critique was that the study severely under-measured the benefits of integration.* While its cost-benefit analysis only counted the income gains based on estimates from Raj Chetty et al’s work, we pointed out that there are many other benefits you might expect from integration: better mental health, school performance, safety from crime, and so on.

But there’s an even bigger issue here that goes beyond any of these discrete benefits. Which is: there is evidence that integration creates positive feedback loops that change the fundamental dynamics of neighborhood change.

After all, the study’s authors calculated that a major cost of putting low-income housing in higher-income neighborhoods was that the property values in those neighborhoods declined as a result—not, apparently, because of any problems the new housing caused, as crime did not increase, but simply because their neighbors preferred not to live around the kinds of people who live in low-income housing.

But in many ways, that effect—and those preferences—depend on a steady supply of neighborhoods without any low-income housing. In part, this is the sort of “prisoner’s dilemma” that we’ve talked about before: in a policy context in which segregation creates resource-rich winners and resource-poor losers, any hint that your neighborhood or municipality might be going towards the resource-poor loser end of the spectrum is cause for alarm. The issue isn’t one or two low-income buildings per se—it’s the possibility that once one or two come in, the segregating dynamics of the housing market will bring in so many more that the area will become very disproportionately low-income. And even where the issue is one or two buildings—because a given homeowner happens to just have discriminatory preferences—that homeowner can only act on their preferences and leave the neighborhood if there are other neighborhoods without any low-income housing for them to flee to.

But what if every neighborhood had some minimum level of low-income housing? What if there were a metropolitan area with a regional integration plan that eliminated the option of living in a totally segregated higher-income neighborhood, protected by exclusionary zoning and other anti-poor policies?

Well, we don’t know for sure, because no such metropolitan area really exists. But there are urban regions that have instituted integration policies for public schools. And the evidence from those is pretty encouraging.

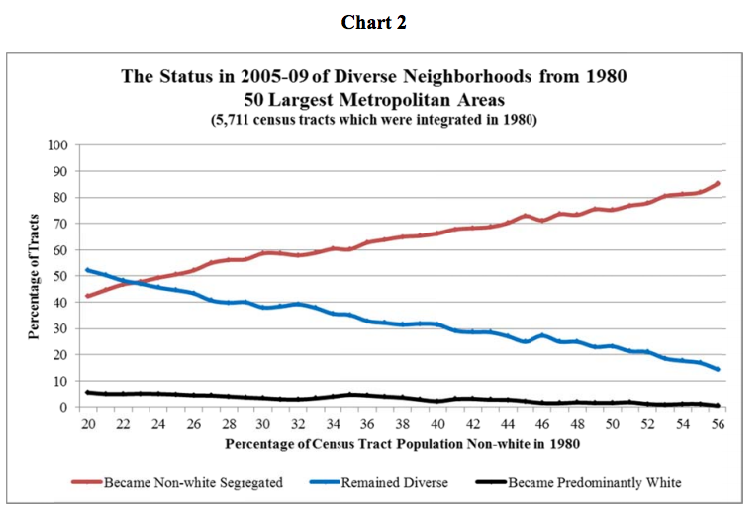

Take this 2012 report from the University of Minnesota’s Institute on Metropolitan Opportunity. In it, Myron Orfield and Thomas Luce look at the trajectories of suburban neighborhoods between 1980 and 2009—asking, for example, how likely it is that a mixed-race community will end up resegregating. The overall numbers are not great: if a Census tract was 23 percent or more people of color in 1980, it was more likely to resegregate than remain diverse by 2009. (The report defined “resegregate” as become less than 40 percent white. Obviously there’s no objective threshold, but the general pattern holds regardless of where you draw the line.) Interestingly—and similar to the results in our “Lost in Place” report—a vanishingly small number of integrated suburban neighborhoods resegregated as white.

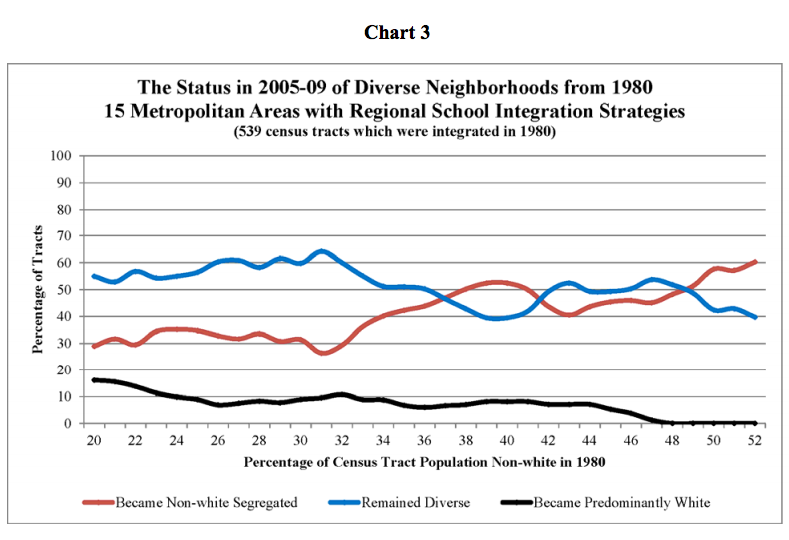

But the report reran these same numbers for 15 metropolitan areas with regional school desegregation initiatives. In other words, these are places where the connection between the demographics of your neighborhood and the demographic of your public school was, to some extent, broken. If a new low-income housing project was built on your wealthy block, then, that wouldn’t necessarily change the demographics of your children’s school, because the desegregation initiative would have already introduced low-income students from other neighborhoods. And by the same token, you wouldn’t necessarily be able to “escape” lower-income students by moving to another neighborhood.

So what’s the result? Well, diverse neighborhoods in these metropolitan areas were much, much less likely to resegregate than similar neighborhoods in regions without school desegregation initiatives. Neighborhoods up to about 37 percent people of color were more likely to remain diverse than to resegregate—and even neighborhoods that were 50 percent people of color in 1980 were only slightly more likely to resegregate, as opposed to having a roughly 75 percent chance of resegregating in regions without school desegregation initiatives.

And this difference is associated just with ending the “prisoner’s dilemma” in schools, not neighborhoods. That is, even if white people are able to access segregated housing, they appear much less likely to want it if that housing won’t guarantee segregated schools. Imagine, then, what might be possible if segregated housing itself were much harder to come by.

* To be fair, the study’s authors acknowledged at one point that they were doing this. Nevertheless, they didn’t change their cost-benefit analysis or conclusions as a result, so our criticism stands.