Yesterday, we introduced our latest report, The Storefront Index, which aims to quantify and map one aspect of a neighborhood’s vibrant street life—customer-facing businesses—in every neighborhood in the 51 largest metropolitan areas in the country. The Washington Post wrote more about it here.

To illustrate one way the Storefront Index can help illuminate urban planning issues on the ground, take February’s Washingtonian article by Greater Greater Washington contributor Dan Reed about a seeming mystery: why are some parks full of people while others are empty?

The article focuses on Farragut Square and Franklin Square in downtown DC. The two spaces are just a few blocks from each other, and are both adjacent to office buildings and a Metro stop, but according to Reed, Farragut is “full of people—eating, strolling, sitting on the immaculate grass,” while Franklin is “desolate.”

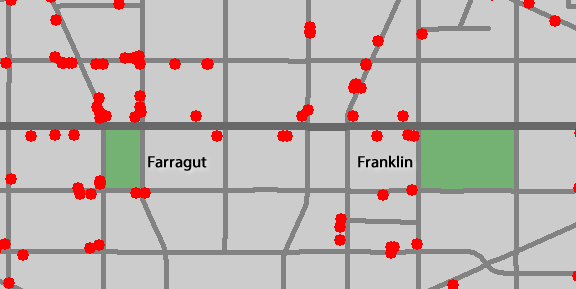

Reed makes a number of hypotheses about why that is, including the design of Franklin Square’s paths and its size. But he also notes that Farragut Square is surrounded by ground-floor businesses, while Franklin Square has only a few on one side. Our Storefront Index map illustrates the issue:

The stores around Farragut Square help keep a steady stream of people dropping by to get lunch or buy a newspaper, some of whom will stop to talk to a colleague they run into, or take a seat in the park to eat or read. At Franklin Square, there’s little to generate that kind of foot traffic—and because people generally like to congregate in places where there are other people, that becomes a self-reinforcing cycle.

As Jane Jacobs observed decades ago, when they work well, urban spaces are a dynamic and symbiotic mix of the public and private: public spaces like parks and squares and sidewalks provide places for walking and sitting and being in public. Shops, restaurants, and bars—particularly when they are clustered together—stimulate the hustle and bustle that conveys a sense of activity, interest and safety that helps activate the public realm.

In this case, Reed found an underused space in his daily life, and realized that the different concentration of businesses could be part of the problem. The Storefront Index can be useful in cases like this to quickly and clearly demonstrate to people who aren’t familiar with these spaces how their commercial character differs.

But planners and active neighbors can also use the Storefront Index to identify public spaces that may not be used to their full potential by looking for parks and squares with few storefront businesses around them. As we update the Index over the coming years, they will also be able to see how changing numbers and locations of storefront businesses track perceptions or data about street life and neighborhood vibrancy.