“For Rent” signs are popping up all over Portland, signaling an easing of the housing crunch and foretelling falling rents

A year ago, in the height of the political season in deep blue Portland (in a county which voted 76 percent for Hillary Clinton) only one thing was rarer than Donald Trump lawn signs: For Rent signs. Portland was facing a housing shortage. Vacancy rates had been plummeting, and in early 2016, apartment rents were going up at double digit rates. The housing crisis prompted the City to adopt an ill-advised inclusionary zoning ordinance, and led the state to flirt with authorizing rent control. That was then.

What a difference a year makes. More new apartments are coming on line, and now for rent signs are more plentiful than mushrooms after the first autumn rains. Take a look:

[table id=10 /]

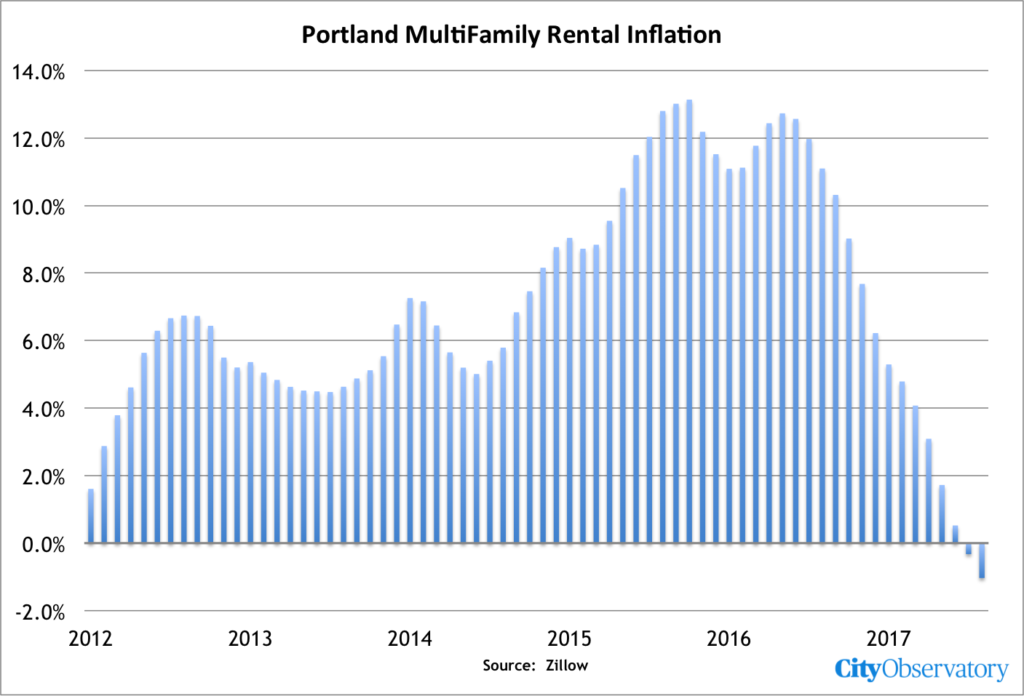

We photographed these signs in the space of about an hour on a recent sunny afternoon in Portland’s close-in East side neighborhoods. These signs are all in front of existing, older apartments. In addition, the Portland area is seeing an increasing number of new apartments coming on to the market. Between freshly built new apartments and a profusion of vacancies in existing buildings, the rental market appears to be changing. After lagging well behind growing demand for the past several years, housing supply is catching up. And this is just starting to have an effect on rents. According to data compiled by Zillow, inflation in Portland area rents fell from a peak of more than 10 percent year over year in 2015 and 2016, to less than zero in August 2017.

The big question going forward is whether rents will decline in earnest. The current abundance of vacancies and the 19,000 or so new apartments in the pipeline in the City of Portland and coming on the market in the next few months suggest that this is a distinct possibility.

What’s happening here is a good example of how the market works. To be sure, Portland, like a lot of cities, has experienced a temporal mismatch between demand and supply. In the wake of the great recession, demand turned around quickly as more people moved to the region and job growth returned, but new apartment construction has taken several years to rebound from the downturn. For several years, culminating in 2015 and 2016, demand outpaced supply, and pushed down vacancy rates, causing rents to surge. Now it appears the reverse is true–the number of new units being delivered to the market is growing faster than demand for housing–which is producing this bumper crop of for rent signs. The more apartments stand vacant, and the longer they go unfilled, the greater the pressure on landlords to drop prices. Already, some newer apartments are offering move-in bonuses, like a months’ free rent. It’s a sign that the market is turning.

What the signs mean

Ultimately, we think this flowering of “for rent” signs disproves two of the most durable myths about the housing markets.

The first myth is that you can’t make housing affordable by building more of it, particularly if new units are more expensive than existing ones. The surge in vacancies in existing apartments is an indication of the interconnectedness of apartment supply, and an illustration of how construction of new high end, market-rate units lessens the price pressure on the existing housing stock. When you don’t build lots of new apartments, the people who would otherwise rent them bid up the price of existing apartments. The reverse is also true: every household that moves into a new apartment is one fewer household competing for the stock of existing apartments. This is why, as we’ve argued, building more “luxury” apartments helps with affordability. As our colleagues at the Sightline Institute recently observed, you can build your way to affordable housing. In fact, building more supply is the only effective way to reduce the pressure that is driving up rents.

The second myth is that high rents are somehow the product of an epidemic of greed on the part of landlords. There’s no evidence in Portland that landlords have suddenly had a change of heart, renounced avarice and decided to stop raising rents. Landlords find it difficult to get new tenants if they’re charging higher rents than the apartment down the street. With so may “for rent” signs, landlords who want to hike the rent are going to have to wait a long time to find tenants. As our colleague Daniel Kay Hertz observed, the reason that housing is more affordable in Phoenix than San Francisco is not because Arizona landlords are somehow uniformly kindlier and more generous, but because the supply of housing is so much more elastic. The most effective check on “greedy landlords” is lots of competition, in the form of more supply.

We’ll watch the situation closely in the next few months, but all the signs point to an improvement in Portland’s housing affordability.