We’ve known for a long time that housing shortages are a major driver of high housing prices—and that, as a result, places that prevent new construction also tend to have big affordability problems.

But now, for the first time that we’re aware of, researchers have taken the next step to showing directly that places like that prevent new construction end up inducing more displacement of their low-income residents.

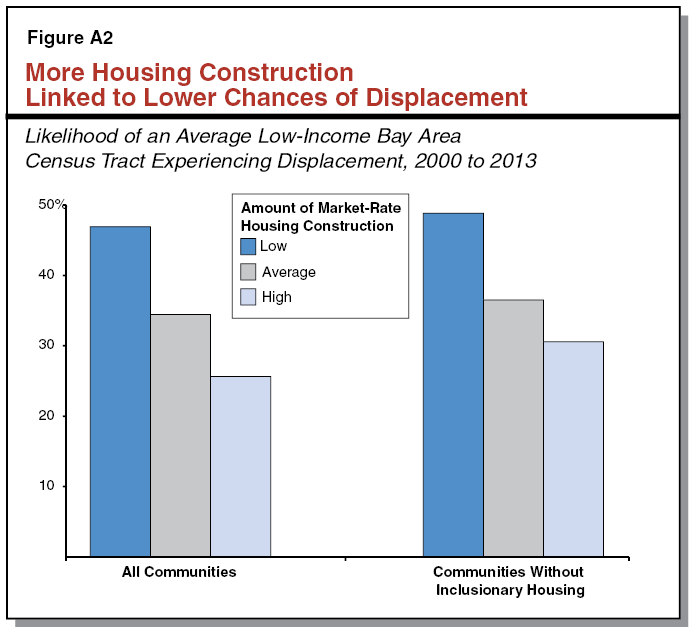

That finding comes from California’s Legislative Analyst’s Office, which just released a new report on the state’s ever-growing affordability crisis. Using a broad definition of displacement—any decline of a neighborhood’s low-income population relative to its total population—the LAO shows that, even controlling for other demographic factors, Bay Area communities with the greatest expansion of market-rate housing also see the least low-income displacement.

The effect is strong: changing from a low-construction neighborhood to a high-construction neighborhood was associated with a decline in the probability of displacement from 46 percent to 26 percent.

And crucially, the LAO researchers found that this effect was independent of inclusionary housing programs. That is, new construction reduced displacement not because it included low-income set-aside units, but because it helped keep market prices lower. In fact, the presence or lack of an inclusionary housing policy had a much, much smaller effect on displacement than the amount of market-rate housing construction.

That’s the headline, but there’s much more to see in the report. It covers the challenges to expanding many of the state’s low-income housing assistance, and demonstrates the importance of filtering to creating “naturally occurring” affordable housing—and how zoning restrictions hamper that process. It bears close reading for anyone invested in creating affordable communities.