The growth of concentrated poverty has been fueled by the secession of successful African Americans

David Rusk has summarized his research on race and economic polarization in a series of three commentaries on “The Great Sort,” for the DC Policy Center. The essence of the sorting in question is the sorting of the nation’s African American population by income. In the heyday of segregation, black Americans had little choice about where to live, and so, regardless of income or profession, rich and poor black Americans tended to live in the few neighborhoods in which they were allowed. But as segregation has eased, some, but not all, black Americans have moved out. And that’s where the sorting comes in: disproportionately better educated and higher income households have moved to more integrated neighborhoods, while less educated and lower income households have tended to remain in traditionally African American neighborhoods. This Great Sort has had the effect of increasing income polarization within the black community and producing higher levels of concentrated poverty.

Rusk has a long and distinguished pedigree in urban policy; he served as the Mayor of Albuquerque and was a researcher for the Washington Urban League and is author of the book “Cities without Suburbs.”

Rusk’s analysis is based on the comprehensive tabulations of Census data by Dr. John Logan and his colleagues at Brown University. You can look up data and profiles for individual metropolitan areas at their website.

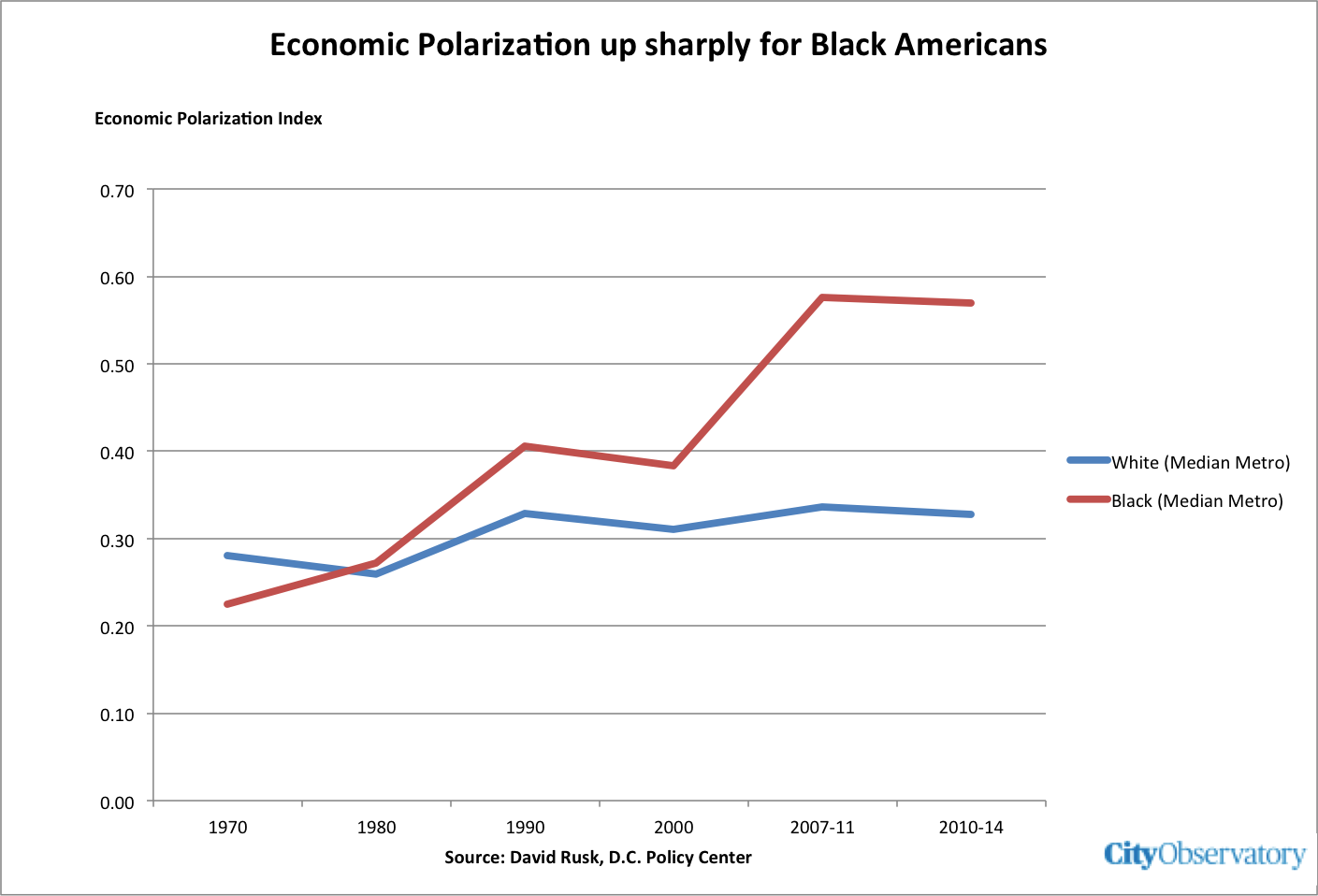

Rusk’s key measure is what he calls the “economic polarization index.” This index is the sum of two other segregation indices computed by Logan: the 10th percentile economic dissimilarity index and the 90th percentile dissimilarity index. These two dissimilarity indexes measure how segregated the poorest (10th percentile) and the richest (90th percentile) members of any racial ethnic group are from all the other members of that racial ethnic group. Each dissimilarity index runs from 0 (perfect integration) to 100 (perfect segregation), and corresponds to the fraction of the population in each group that would have to move to a different neighborhood in order to produce an identical distribution of income groups in each neighborhood. Importantly, these indexes are computed separately for each racial/ethnic category: high income African Americans are compared to all other African Americans, for example.

Rusk has a crisp synthesis of the import of his statistical analysis:

Black economic polarization increased in all 58 of 58 metro areas for which indices were calculated. Most telling are the 48 metro areas that had significant Black populations in 1970; economic polarization was somewhat lower among Black household (22.5) than among White households (27.7) as the Black population – regardless of economic status – was still packed into racial ghettos. (The federal Fair Housing Act had just been enacted in 1968.)

Thereafter, the Black middle class and, especially, affluent Black households exploded into suburban communities (often into more newly constructed subdivisions as in Metro Washington’s Charles and Prince William counties). Many poor Black households remained trapped in “legacy housing” (e.g. public housing projects). Even programs hypothetically designed to disperse poor Black households, such as federal Housing Choice Vouchers, have, in practice, concentrated most voucher holders in high minority, high poverty neighborhoods.

Thus, Jim Crow by income is steadily replacing Jim Crow by race.

Logan’s data starts in 1970 and runs through 2014. The 1970 starting point corresponds to the very early years of the civil rights era; the Fair Housing Act had just passed in 1968, and overall levels of racial segregation in the US were near their peak.

A closer look at the 50 largest metro areas

David Rusk graciously shared his metro level tabulations with City Observatory, enabling us to look more closely at just the group of the 50 largest metro areas we follow here on a regular basis. What follows is a summary of the data for these large metropolitan areas, with detailed metro level figures on black and white economic polarization in 1970 and 2010-14.

Rusk’s economic polarization index shows that in 1970, in large metropolitan areas, black Americans were far less segregated by income than were white Americans. The median large metropolitan area in the US had a polarization index of .22 for blacks compared to a polarization index of .28 for whites.

Since 1970, economic polarization has increased dramatically for Black Americans but has increased only slightly for whites. The economic polarization index for blacks more than doubled from 1970 to 2010-14, from .22 to .57. The economic polarization index for whites rose from .28 to .33. The increase for blacks was seven times greater than for whites: up .35 for blacks versus just .05 for whites. On average, high income black households live much more segregated from low income black households than high income white households live from low income white households.

Detail on the changes by metropolitan area show just how widespread and pervasive this pattern has become. In 1970, just six of 38 large metropolitan areas had higher economic polarization rates for whites than for blacks. By 2010-14 all large metropolitan areas had greater economic polarization among their black population than amount their white population.

Metropolitan Data

The story behind this trend is straightforward: in the wake of the civil rights movement, higher income black households have been able to choose to move to different neighborhoods; while lower income black households have not.

As William Julius Wilson explained in 1978, up until the 1960s and early 1970s, the most well-educated and higher-income African Americans had little choice but to live in racially segregated neighborhoods, where they provided community leadership and role models. More recently, the lessening of de-facto and de jure racial segregation gave them more choices of where to live. In the process, their migration undermined the cohesiveness and economic diversity of their neighborhoods—actually intensifying the effects of economic segregation for the population who stayed (Wilson, 1978).

This telling squares with the frequently nostalgic accounts of life in formerly vibrant, if highly segregated neighborhoods. There were thriving African American business centers and cultural institutions, communities were stable, and as the Rusk data show, though African-Americans had lower incomes on average, higher income families in the black community were less segregated from low income black families than was the case for whites.

The decline of African American neighborhoods was driven as much by the pull of opportunity in the wake of civil rights legislation as by the “push” of displacement from urban renewal and highway building. Population of many historically African American neighborhoods declined, especially after 1968, but those who left tended to be the ones with the most income, and the most education, while those who remained behind tended to be less educated and more likely to be living in poverty. The higher income households that left traditionally black neighborhoods as desegregation progressed “disinvested” in these places just as surely as any bank, business or public institution. As they left, the community was deprived not just of their financial capital and spending power, but their social and cultural leadership.

Rusk’s economic polarization index is just one way to measure the sorting of households by income. But his findings are consistent with a range of other academic research. Patrick Sharkey found that the proportion of middle- and upper-income black households grew from 33% in 1970 to 58% in the late 2000s, and the proportion in suburban neighborhoods grew from 19% in 1970 to 48% in the late 2000s. Similarly, The Brookings Institution’s Jenny Schuetz examined the relationship between income, by race and ethnicity and distance from the city center in 24 large metropolitan areas. She found that for blacks and Latinos, income was positively associated with distance from the center-i.e. that higher income households tended to live in more suburban locations, consistent with the observation that since the legal desegregation of housing markets, black and Hispanic middle class families have moved to the suburbs, leaving their poorer neighbors in central cities.

While some black households with higher incomes have managed to move to richer, more ethnically diverse neighborhoods (often with better schools, and often in the suburbs), lower income black households have become increasingly concentrated in neighborhoods that are poorer, and have lower public services. The net effect of the sorting that Rusk describes has been to aggravate the problem of concentrated poverty which disproportionately affects people of color. Our Lost in Place report calculates that 75 percent of the persons living in urban neighborhoods of concentrated poverty (with poverty rates of 30 percent or higher), are African American or Latino.