Carbon emissions from transportation in Portland increased 6 percent last year

In the one are where city policy can make the most difference, greenhouse gas emissions are increasing

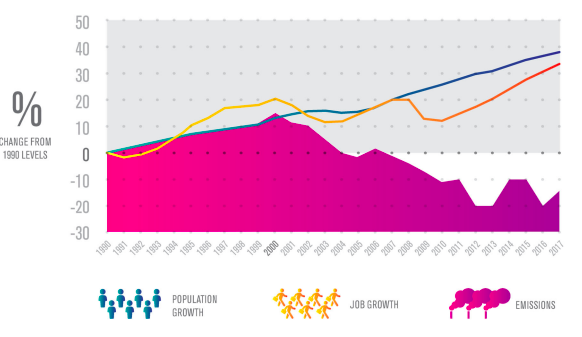

Portland has long prided itself in being one of the first cities in the US to adopt a legislated goal of reducing its greenhouse gas emissions. The city’s latest carbon emission inventory report shows that the city is failing to meet these goals. Not is the city far from the glide slope needed to reach its target, carbon emissions are actually increasing–primarily due to more driving. Transportation is now the largest source of Portland’s greenhouse gas emissions, and have risen more than 6 percent in the past year–mostly offsetting gains in other sectors.

The city’s report concedes that this is a problem:

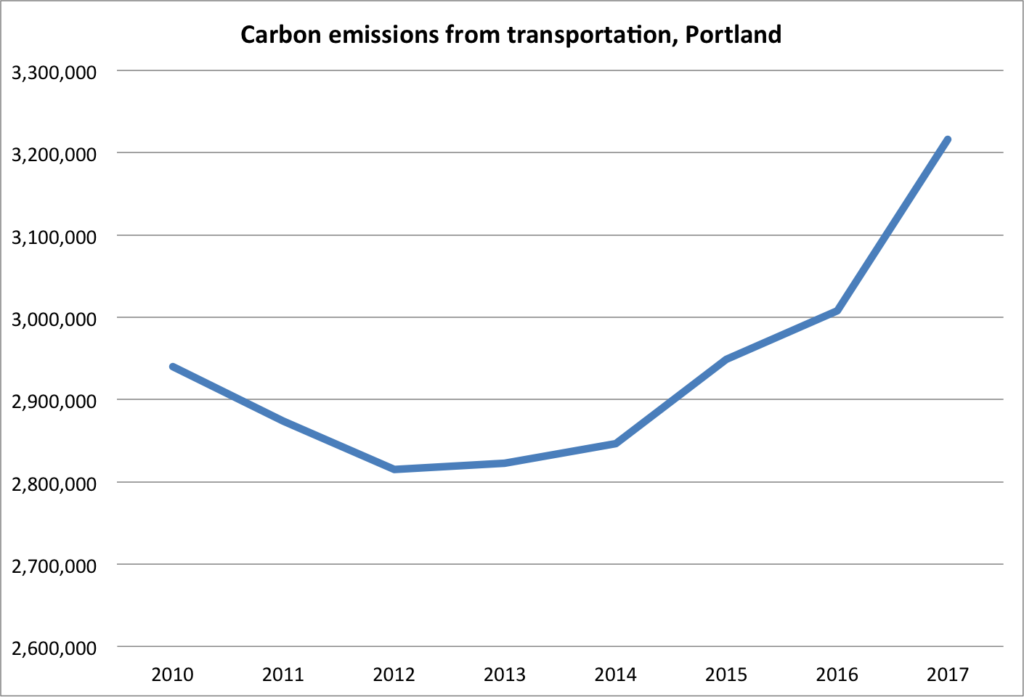

Transportation sector emissions are increasing dramatically, currently 8 percent over 1990 levels, and 14 percent over their lowest levels in 2012. Portland has experienced year over year increases in transportation-related emissions for the past five years, with transportation emissions growing faster than population growth over the same period.

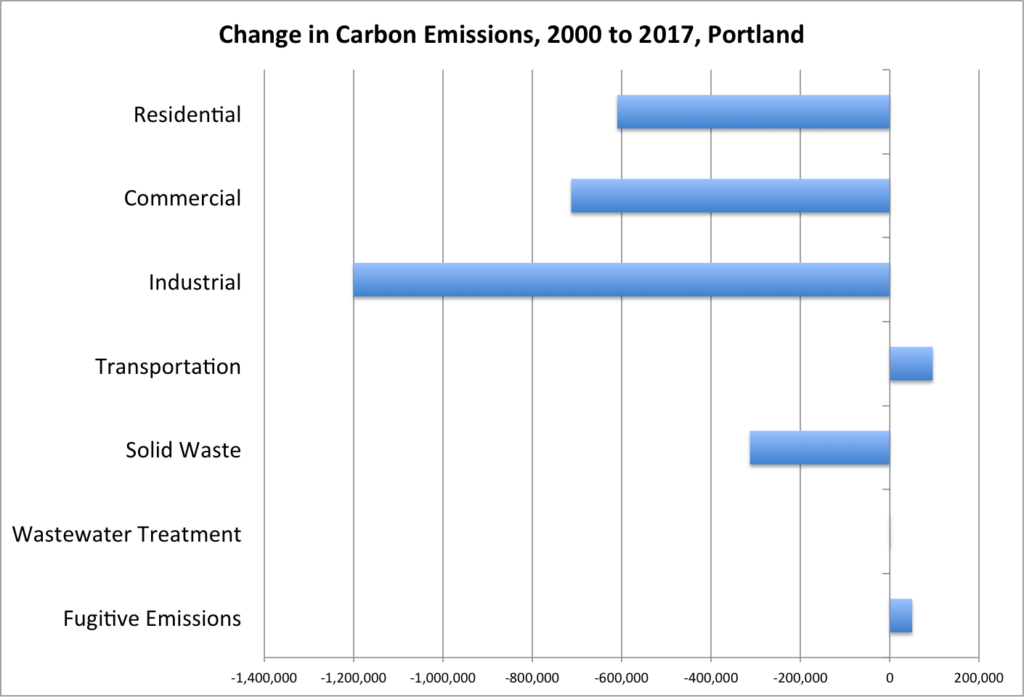

The failure to make progress in the transportation sector is especially apparent when we look at the change in carbon emissions by source.

Since 2000, more than 70 percent of the carbon emission reductions have come from savings in the commercial and industrial sectors. Over that same period, the city has made no net progress in reducing carbon emissions from transportation. While residential emissions are down about 30 percent–thanks in part to cleaner energy sources for electric generation and home heating and weatherization–the one area where local policy is likely to make the most difference–in transportation energy consumption–the city is failing.

Falsely attributing transportation emissions to job growth instead of cheap gas

The city’s climate report seems to be in denial about the causes and the seriousness of the rise in transportation emissions. It tries to attribute rising emissions to an improving economy, claiming (page 9):

. . . transportation sector emissions have increased in recent years. The increase in transportation emissions has tracked closely with the recovery from the 2009 recession.

This claim is false. Transportation-related emissions actually fell between 2010 to 2014, when the Multnomah County added 44,000 jobs. The report fails to mention that all of the increase in transportation emissions came after 2014–when gas prices fell by more than a third, prompting more driving. As long as gasoline prices were high, even with five years of economic growth, driving and transportation emissions continued to decline. In addition, the report emphasizes that the region has achieved per capita reductions in driving and gasoline consumption, and tries to blame increased transportation emissions on rising population; yet other sectors (residential, industrial and commercial) are managing to achieve absolute reductions in emissions even though we’re housing, employing and serving a considerably larger population.

Ignoring the critical role of prices, and shifting the focus to per capita changes in consumption (which are good) while ignoring aggregate emission increases undercuts a serious look at what is needed to achieve the region’s climate goals. Transportation is now far and away the largest source of Portland’s greenhouse gas emissions, and they will only be reduced if we change the price of driving to reduce vehicle miles traveled.

Plateauing = Failing

Portland’s Bureau of Planning and Sustainability seems to be putting this failure to make progress in recent years as a “plateauing” when in fact it represents a significant failure. The Portland Tribune reported:

“We’ve had a lot of success in reducing emissions,” said Planning & Sustainability Director Andrea Durbin. “That’s big.”

All of that “success” stopped in 2012, total emissions are up since then.

Here’s the thing: in the climate arena, plateauing is actually backsliding. Unless the city reduces emissions each year, it falls further and further behind in meeting its goal. In essence, the city has lost five years. Those five years will have to be made up, and the task ahead is even tougher: we’ve already done the cheapest, easiest things to reduce emissions (like replace residential oil heating with natural gas). It’s also worth noting that most of the emission reductions aren’t attributable to city policies– much of the success has been the result of state and federal policies–like increased renewable power and declines in coal fired electricity generation.

The city staff recognize that more is needed, but exactly what isn’t clear. According to Durbin, (again from the Portland Tribune):

Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler believes part of the solution is for the City Council to declare a climate emergency sometime next year. Staff at BPS have been directed to reach out to youth, communities of color and other groups this fall.

Durbin says the mayor also is considering a new ban on fossil fuel infrastructure . . .

If one is intent on banning new fossil fuel infrastructure a good place to start would be by reversing course on the proposed half-billion dollar Rose Quarter freeway widening project, which would increase driving and add to carbon emissions.

Bottom line: Despite making progress between 2000 and 2010, Portland is now falling further and further behind in its pledge to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, almost entirely because we’re driving more. The failure to connect the dots–low prices for fuel stimulate more driving–means we’re likely to fall further behind in the years ahead, unless we do something dramatically different.

On Friday, along with other cities, young Portlanders will participate in a national climate strike–this report shows that their concerns are justified, and that the city needs to do much more if it is to achieve its lofty goals. We hope Portland’s leaders will be listening.

Bureau of Planning and Sustainability,

Multnomah County 2017 Carbon Emissions and Trends,

September 18, 2019

https://www.portlandoregon.gov/bps/article/742164