In auto-land, pedestrians are just one more patented gimmick away from being safe

The dominant approach to automobile safety has, for many years, been the quintessential technical fix. Some combination of new technologies (anti-lock brakes, collapsible steering columns, crush zones, multiple air bags, etc) will make cars safer and safer (well, at least for their occupants). And soon, self-driving cars will (it is hoped) eliminate human errors that produce most crashes.

Still the humble pedestrian remains under-engineered for this brave new world of technologically assured density. But that’s changing.

Some months back, we noted that Google unveiled drawings of a novel plan to coat the exterior of self-driving cars with a special adhesive that would cause any pedestrians the vehicles struck to adhere to the car rather than being thrown by the impact. Now, Automotive News is sharing reports of a new General Motors patent that would put airbags on the outside of cars to deflect errant pedestrians.

Whether it would be better to find oneself stuck to the car that struck you, or being pushed aside by an exploding airbag, is far from clear. But let it not be said that automotive engineers and major corporations are the only ones who can come up with such far-fetched ideas. Here at City Observatory, we’ve come up with our own concepts for, if you will, lessening the impact of cars on pedestrians. In the interest of safety and advancing the state of the art, we’re putting our ideas into the public domain, and not patenting any of them.

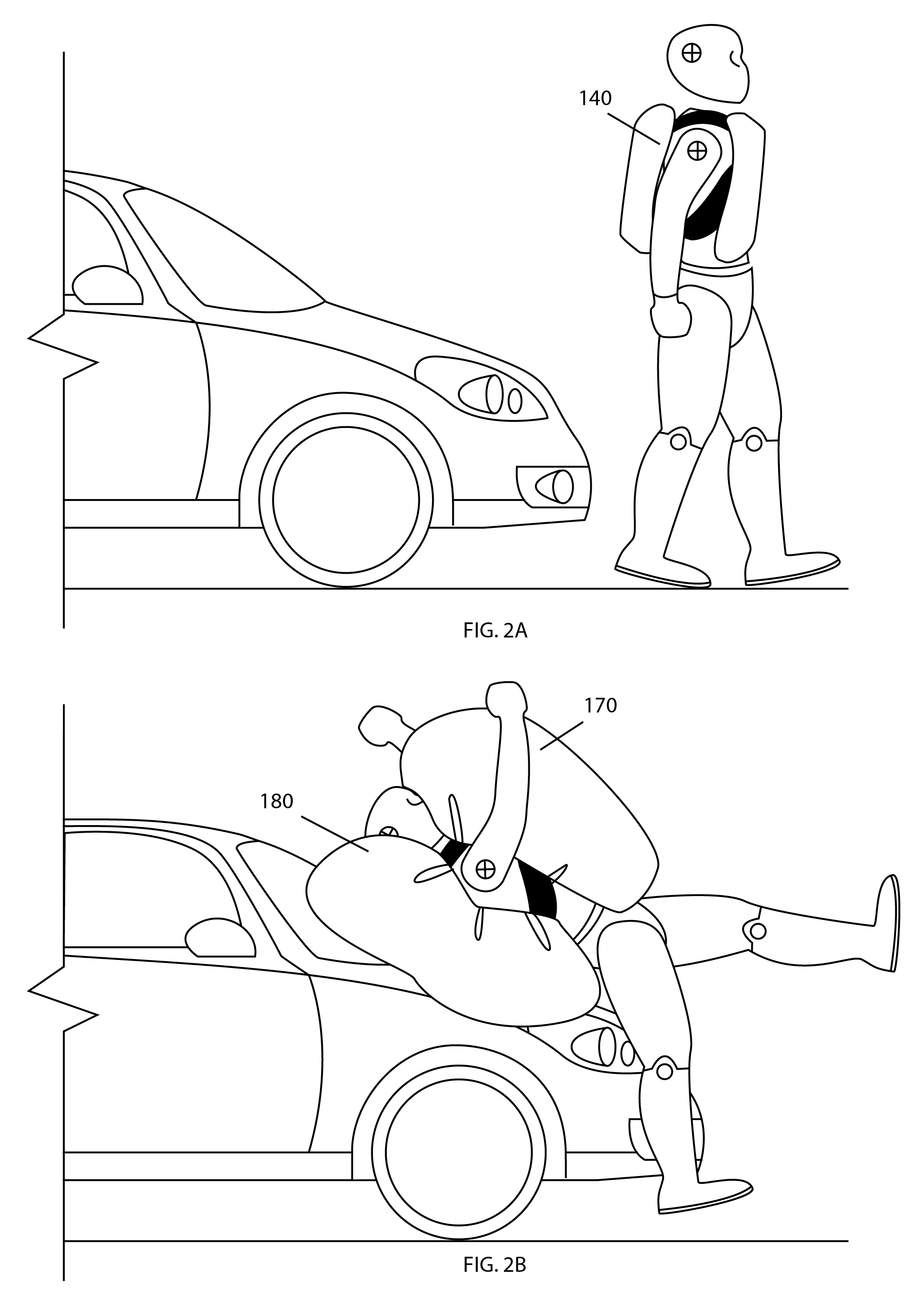

Personal airbags. Airbags are now a highly developed and well-understood technology. Most new cars have a suite of frontal impact, side curtain and auxiliary airbags to insulate vehicle passengers from collisions. The next frontier is to deploy this technology on people, with personal airbags. Personal airbags could have their own sensors, inflating automatically when the pedestrian was in imminent danger of being struck by a vehicle.

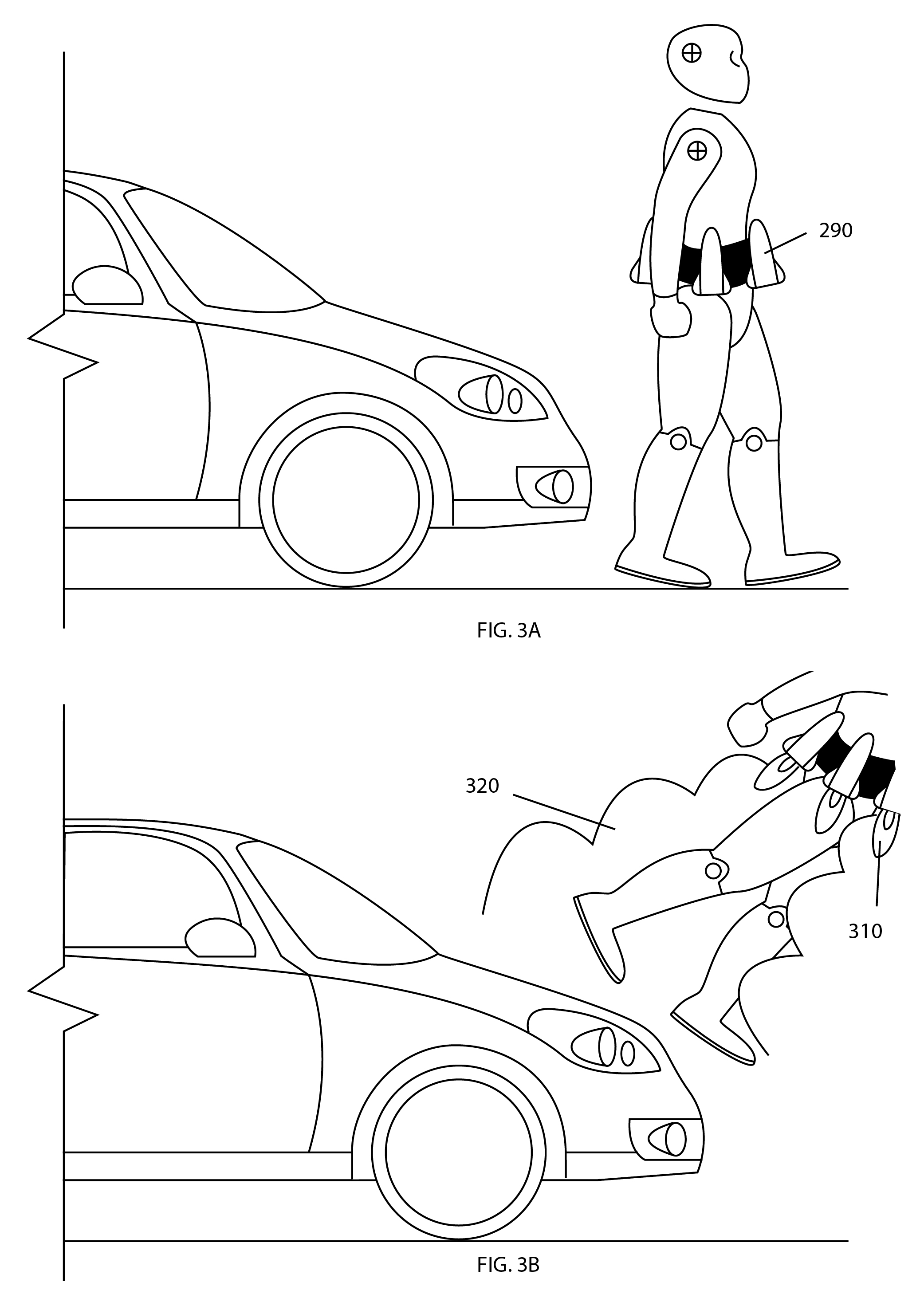

Rocket Packs. While a sufficiently strong adhesive might keep a struck pedestrian from flying through an intersection and being further injured, perhaps a better solution would be to entirely avoid the collision in the first place by lifting the pedestrian out of the way of the collision in the first place. If pedestrians were required to wear small but powerful rocket packs, again connected to self-driving cars via the Internet, in the event of an imminent collision, the rocket pack could fire and lift the pedestrian free of the oncoming vehicle.

We offer these ideas partly in jest, but mostly to underscore the deep biases we have in thinking about how to adapt our world for new technology. Let’s be clear: while these are labeled “pedestrian safety” technologies, they are really about making the environment better for cars and driving. Like crosswalks and electronic “walk-don’t walk” signs, these are not technologies that are needed in pedestrian-only environments. No matter how crowded, no mall, stadium, or concert hall has stoplights for pedestrians.

It has long been the case with private vehicle travel that we’ve demoted walking to a second class form of transportation. The advent of cars led us to literally re-write the laws around the “right of way” in public streets, facilitating car traffic, and discouraging and in some cases criminalizing walking. We’ve widened roads, installed beg buttons, and banned “jaywalking,” to move cars faster, but in the process making the most common and human way of travel more difficult and burdensome, and make cities less functional. And at some point, the existence of these kinds “pedestrian protection” technologies becomes a basis for rationalizing making the physical environment even more hostile to actual humans. The ultimate objective of much engineering practice seems to be to exterminate walking (if not walkers). As one Washington State engineer bluntly described Seattle’s 1950s era transportation plan: “Pedestrians, who are a constant hazard to city driving, are entirely removed.”

Everywhere we’ve optimized the environment and systems for the functioning of vehicle traffic, we’ve made places less safe and less desirable for humans who are not encapsulated in vehicles. A similar danger exists with this kind of thinking when it comes to autonomous vehicles; a world that works well for them may not be a place that works well for people.

Not all of our problems can be solved with better technology. At some point, we need to make better choices and design better places, even if it means not remaking our environment and our communities to accommodate the more efficient functioning of technology.

Thanks to Matt Cortright for providing the diagrams for our proposed pedestrian protection devices.