Oregon is utterly failing to reduce transportation greenhouse gas emissions

Instead of being down 10 percent by 2020, transportation greenhouse gas emissions are up more than 20 percent

Oregon will miss its 2020 GHG goal by 6.5 million tons per year

ODOT’s so-called “strategy” is really technocratic climate denial

In 2007, Oregon boldly adopted the policy of reducing its greenhouse gas emissions by 75 percent from their 1990 levels by 2050. The Legislature also set an interim goal of reducing greenhouse gases by 10 percent by 2020. Since transportation emissions are the single largest source of greenhouse gases in the state, much of the responsibility for meeting this goal necessarily depends on transportation policy.

The 2010 Legislature directed the Oregon Department of Transportation to fashion a strategy for meeting that goal. It labored, and came forth with an 130-page document in 2012, called the STS or State Transportation Strategy. That document was presented to–but significantly, not adopted by–the Oregon Transportation Commission. In 2018, the department published an update report presenting some emissions data and describing implementation efforts. On paper, at least, we’re led to believe that ODOT has an ongoing plan for addressing climate change. But independent data on emissions tells a different story.

The tale of the tape: Rising transportation greenhouse gases

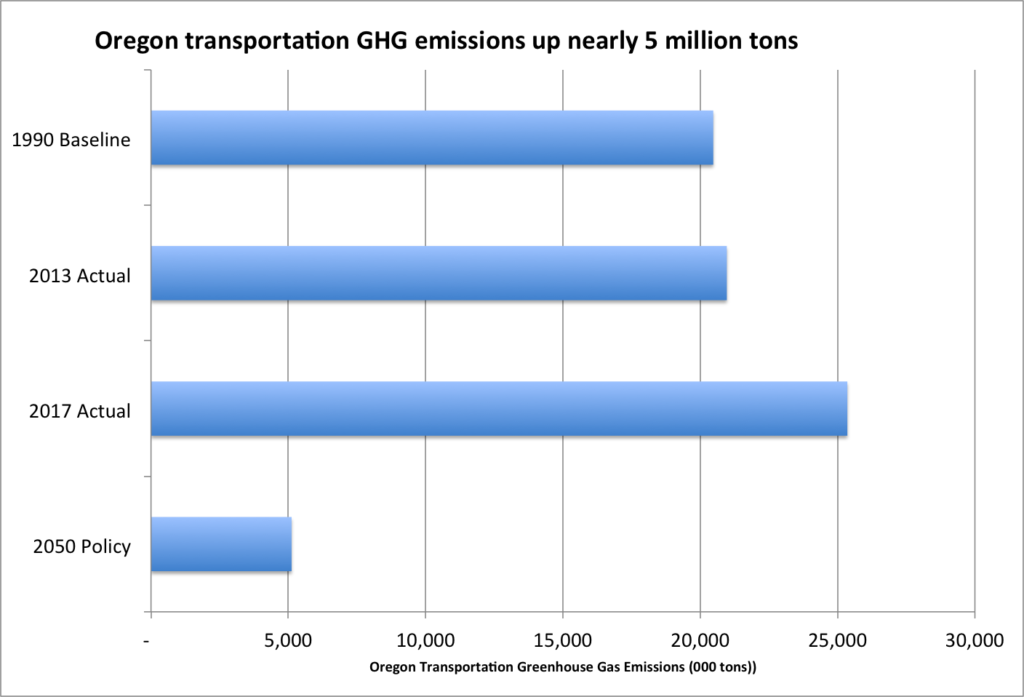

The tragic fact is that the state’s own greenhouse gas monitoring efforts show that the strategy is failing–utterly. In order to meet the state’s goal of a 75 percent reduction from 1990 levels, greenhouse gases from transportation–which were about 25 million tons in 1990–would have to fall to about 5 million tons per year by 2040.

In the past four years, according to data published by the State Department of Environmental Quality, greenhouse gases from transportation have increased by more than 20 percent statewide, from 21.0 million tons per year to 25.3 million tons per year. (Transportation emissions include sources other than cars, such as trucks, trains and aircraft, but automobiles and light trucks are the largest component of transportation emissions).

ODOT’s 2018 monitoring report concedes obliquely that it won’t come close to meeting the state’s climate reduction goals, but claims (falsely) that the state is making progress. As the report says:

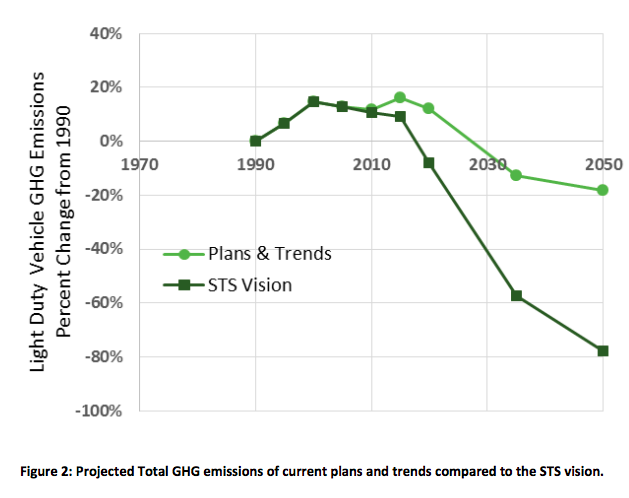

The chart below (Figure 2) shows an estimate of GHG emissions projected from current plans and trends, compared to the STS vision. The chart shows an uptick in emissions following the recession and projected reductions in the long term. In the long term it is assumed that vehicles get more efficient, which helps to bring the curve down. While the overall trend line is moving in the right direction, it falls short of the levels called for in the STS vision.

One key fact is missing from the 2018 monitoring report: the actual volume of greenhouse gases emitted by transportation. Figure 2 shows, very crudely and without much detail, an increase in greenhouse gases from 2010 to some unspecified year between 2010 and 2020 shows the “plans and trends” (light green) rising compared to a “STS vision” line (dark green declining).

Transportation GHG: Going rapidly in the wrong direction

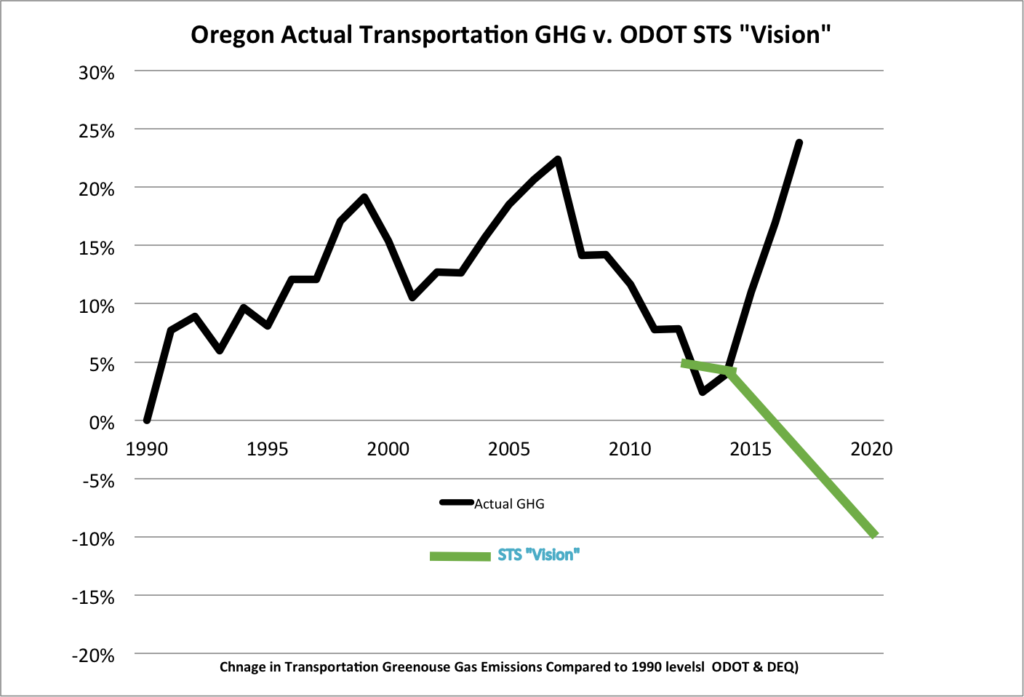

Let’s take a close look at the actual annual data for Oregon transportation greenhouse gas emissions as tabulated by the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality. They show year-by-year after 2012 a steady increased in transportation greenhouse gases.

Between 2013 and 2017, according to DEQ estimates, transportation GHGs in Oregon increased by more than 20 percent. Contrary to what ODOT describes as an “uptick” and an “overall trendline going in the right direction” Oregon is going rapidly in the wrong direction.

How much so?

Oregon will miss by a wide margin its policy of reducing greenhouse gases by 10 percent from 1990 levels in 2020, at least as applied to transportation. Instead of declining by 10 percent, transportation greenhouse gases will be up more than 20 percent (barring a dramatic reversal of the last four years trend). And, if the current trend continues, Oregon’s transportation greenhouse gas emissions will be 25 percent higher than in 1990, missing the goal by 35 percentage points.

Since the STS was written in 2012, Oregon has gone dramatically in the wrong direction. Focusing on percentage point changes tends to obscure the enormous size of the emissions increase: Oregon’s transportation greenhouse gas emissions have increased by 4 million tons per year. If emissions manage to stay flat from 2017 through 2020, Oregon will miss its greenhouse gas reduction target by 6.5 million tons per year.

The problem looks even more daunting going forward. The following chart shows the level of transportation greenhouse gases in Oregon in 1990, 2013, and 2017, and the level of greenhouse gases implied by the state’s goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 75 percent from 1990 levels. Through 2013, we had made essentially no net progress compared to 1990. Over the next four years, as noted above, we went dramatically in the wrong direction. Today, to meet our 2050 goal, we have to reduce greenhouse gases from transportation by 20 million tons per year, from 25 million today, to just 5 million in 2050.

Going in the wrong direction makes the task going forward vastly harder. In 2007, when the greenhouse gas policy was adopted, Oregon had 43 years to manage a 15 million ton reduction in transportation greenhouse gases; the state had to figure out how to reduce transportation emissions on an annual basis by about 350,000 tons per year each year to meet its 2050 goal. In 2020, with average emissions of about 25 million tons, we have just 30 years to make a now larger 20 million ton reduction, which works out to reducing transportation GHGs by 660,000 tons per year each year. The road has become almost twice as steep, and becomes more so each year we fail to make progress.

While ODOT acknowledges it may only reduce transportation greenhouse gases by a fraction of those mandated by state law, its report still characterize its efforts as “on track” in its conclusion:

With current efforts and our newer plans, Oregon is on track to reduce GHG emissions by 15-20 percent below 1990 levels by 2050, which falls far short of the STS vision.

The only sense in which this is “on-track” is that it is on track to fail. And this claim of a 15-20 percent reduction is based on no evidence showing how ODOT expects to reverse the more than 20 percent increase in transportation greenhouse gases in the past four years, much less generate additional, continued reductions in emissions.

In theory, the huge miss on the 2020 goal and the big increase in transportation greenhouse gases in the past four years ought to prompt additional, much more aggressive action. But that doesn’t appear in the 2018 update.

The plan is failing, and ODOT is doing nothing to respond

Even though the strategy calls for updates and bold action, the latest report, while conceding that the state’s efforts are inadequate, proposes no new actions. The original STS report promised regular adjustments, based on performance:

. . . the STS will be monitored and adjusted over time, as needed. While there are challenges and unknowns ahead that will require continuous adaptation and development of additional creative solutions, the groundwork established in the STS provides a fi rm base from which to build. Strategies already underway will receive increased support and new, effective and aggressive strategies that require enhanced levels of collaboration between the private and public sectors and across all transportation markets will be implemented.

(Oregon Statewide Transportation Strategy, 2012, page 108)

Significantly, while the STS was submitted to the Oregon Transportation Commission, it was “accepted” by that body, rather than adopted as a statement of policy. As a matter of law, the STS has no regulatory force, nor has the commission done anything other than say that they’ve read it.The STS is more an implausible conjecture than an actual plan. It’s a laundry list of largely speculative actions , all of which would be needed to be implemented by someone, but with no timetable or accountability for their actual implementation.

Even though it hasn’t been adopted and has no force of law, the STS functions as a kind of talismanic fig leaf for ODOT when it comes to climate concerns. Pressed by activists to acknowledge the seriousness of the climate crisis, OTC commissioners and department managers can point to the STS as their “plan” for responding.

The STS isn’t so much a plan as a carefully rehearsed list of excuses for failure

The trouble is, the plan does next to nothing to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The bulk of the STS consists of projections of age, weight and fuel efficiency of the future vehicle fleet, the carbon content of fuels. ODOT counted on a combination of tough federal fuel efficiency standards, a decline in consumer purchases of trucks and SUVs, growing adoption of electrical vehicles, faster replacement of older, dirtier cars and reductions in the carbon content of fossil fuels. As the 2018 STS update makes clear, everyone one of these projections has been wrong: fuel efficiency standards have been gutted, truck and SUV sales are nearly double those of cars, consumers are keeping cars longer than ever, electric vehicle adoption is far slower than forecast, and fuels are dirtier.

Little surprise than emissions have increased rapidly–ODOT isn’t undertaking any actions that would plausibly lead to their reduction. Aside from a few token efforts–like a handful of vehicle charging stations, and an Orego road pricing demonstration (which after four years of operation has only 611 of the 5,000 users it was seeking. Most of those who signed up for the program have dropped out. And, perversely, Orego’s flat per mile fee imposes higher costs on more fuel efficient, low emission vehicles. The STS also makes the unsubstantiated claim that so-called “intelligent transportation systems” (electronic road signs and ramp meters) will produce reductions in greenhouse gases (something its been caught lying about before).

In effect the STS isn’t a “strategy” at all: its an elaborate ruse, designed to deflect responsibility and create an illusion of action that actually allows the agency to continue business as usual.

ODOT’s advisory group includes climate deniers

It shouldn’t be a surprise that this plan is so feeble. In constructing the original plan, the Transportation Department relied heavily on the advice of those who either opposed taking strong action to reduce transportation emissions, or simply didn’t believe in climate change. As the update report makes clear, the Oregon Department of Transportation has selected a group of “stakeholders” including those who are climate denialists. As the ODOT 2018 STS Monitoring report says:

Stakeholder opinions varied from adamant support of the effort to fundamental disbelief in climate change and the need to reduce GHG emissions.

Oregon STS Monitoring Report, 2018, page 1

Stakeholders chosen by ODOT to develop the strategy included the American Automobile Association, the Oregon Trucking Association, and other groups with an interest in road-building. In short, the state’s climate reduction strategy has been authored by a group that is only in favor of meeting the statutorily prescribed objective if its not deemed too inconvenient. As the strategy document concedes:

The stakeholder groups guiding the process recognized the need to understand impacts to other outcomes beyond GHG emissions, such as health and equity. For example, changes to household costs was one of the primary outcomes the stakeholder groups looked to in assessing how hard to push on certain strategies, such as pricing.

And here we have the classic double standard: The Oregon Transportation Commission effectively tells climate activists that it has utterly no discretion to consider the climate impacts of its proposed $800 million freeway widening project, because the Legislature has instructed it to “git ‘er done” and build the project. But when it comes to a definitive adopted requirement to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 75 percent, ODOT defers to the undocumented opinions of a few stakeholders it selects to block a strategy because they think (without evidence) that it may be costly or inconvenient. Moreover, the claims that it would be too costly or inequitable to achieve greenhouse gas reductions aren’t documented anywhere in the STS report.

If anything, reducing driving will reduce the costs incurred by Oregon households. We have estimated that lower rate of driving in the Portland metropolitan area (compared to large metropolitan areas in the US) saves the region’s consumers more than $1 billion per year in expenses on vehicles and fuel compared to what they would pay if Portland were as sprawling and auto-dependent as the typical metro area. Further reductions in vehicle miles traveled reduce household costs.

With each passing day, the enormity of the climate crisis becomes more clear. In Oregon–as in most of the US–the biggest source of greenhouse gas emissions is transportation. In theory, Oregon’s statutory commitment to reduce greenhouse gases should motivate real action, but as state data show, we’re rapidly heading in the wrong direction. The ODOT STS has failed utterly to produce any progress–much stronger steps will be needed if Oregon is to do anything meaningful to address the climate crisis.