The highway department’s claims it doesn’t have enough for maintenance are a long-running con

You’ve all seen the classic street con three-card monte. All you have to do to double your money is follow one of three cards that the dealer is sliding around the on the surface of the little table. No matter how closely you track the cards, when the shuffling stops, and the dealer asks you to pick one, you can be sure that its not the one you thought it would be. It’s a sucker bet, and you always lose.

But there’s another street hustler out there, who thinks the guy with a cardboard box and a handful of playing cards is a penny-ante player. If you really want to see how the three-card monte con works, there’s no one more masterful than the Oregon Department of Transportation.

The game they play is “find the money to fix potholes.” Everyone agrees we need to maintain the very expensive investment we’ve made in our roads and bridges (that, ostensibly is why we pay the “user fees” that go into the state highway fund). But no matter how much money goes into the fund—and the 2017 Legislature passed the biggest fee and tax hike in Oregon’s transportation history—the agency just seems to come up short when it comes to money for maintenance.

ODOT has been working this hustle for a long time (we’ll provide a bit of history in a moment). When it comes to finances the agency is very adept and shuffling the cards—and the money—so that no matter where you look, the money is elsewhere. The latest iteration of the three-card monte was dealt up by Oregon DOT director Kris Stricker, who announced that the agency doesn’t have sustainable funding to maintain the state’s roadways—in spite of the fact that its been less than three years since the Legislature passed a massive funding bill. Here’s the Oregonian’s coverage:

“Many will wonder how ODOT can face a shortfall of operating funding after the recent passage of the largest transportation investment package in the state’s history,” Kris Strickler, the agency’s director, said in a Wednesday email to employees, stakeholders and other groups, citing the 2017 Legislature’s historic $5.3 billion transportation bill. “The reality is that virtually all of the funding from HB 2017 and other recent transportation investment packages was directed by law to the transportation system rather than to cover the agency’s operating costs and maintenance.”

Now keep in mind that the agency got $5 billion in new revenue, and because the agency is marching ahead with several large construction projects (and borrowing billions to pay for them), that won’t leave enough to pay for repairs and agency operations.

But let’s be clear: That’s no accident. ODOT made decisions that created this problem. It understated the costs of big construction projects, and financed them in a way that automatically puts the repair dollars at risk. It told the Legislature that the I-5 Rose Quarter freeway widening would cost $450 million (and its price tag has since ballooned to nearly $800 million and could, according to the agency, easily top a billion dollars). These overruns will be paid for with money that could have been used to repair roads. ODOT is also choosing to pay for these projects by issuing debt secured by its gas tax revenues, and the covenants it makes with bondholders mean that if gas tax revenues go down (and they’re in free-fall now, due to the pandemic), that bond repayments get first priority, and all of the cuts fall on operations and maintenance.

And that’s not all. Not only has the agency chosen to paint itself into this budgetary corner, it also routinely takes money that could be used for maintenance and plows it into big capital projects.

As we’ve pointed out, ODOT has a long series of cost-overruns on its major projects. When a project goes over budget, the agency has to find the money from somewhere—and it always does. A good part of the dark arts of transportation finance consist of figuring out ways to take money in one pot and as the saying goes “change its color” so that it can be placed in a different pot. Two of its favorite tactics are “unanticipated revenue” and “savings.”

Here’s how they work. Sometimes the agency will budget money for a project, and it will cost less than expected (or be scaled back). Then those moneys are now “savings” and are free to be reallocated for other purposes. The “unanticipated funding” is even more obscure. ODOT can adopt a slightly more pessimistic revenue outlook at some point (by assuming for example that Congress lets the federal highway trust fund go broke); when that doesn’t happen the revenue outlook is re-adjusted upward accordingly and voila—there’s “unexpected revenue.” But notice that because the agency is responsible for estimating revenues and costs, it can easily choose to overestimate costs (to produce “savings”) or under-estimate revenues (to produce “unexpected revenue.”)

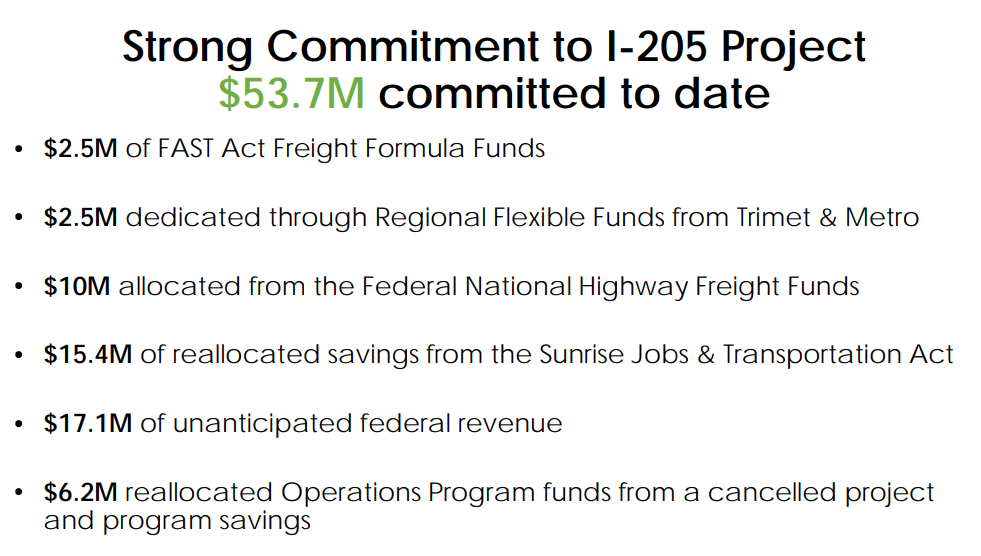

ODOT is currently employing both of these strategies to magically fund the widening of I-205—a project that the Legislature did not provide funding for. Here’s a slide from ODOT’s December, 2018 briefing on the project:

Most of these funds (regional flexible funds, “reallocated savings,” “unanticipated federal revenue” and especially the “operation program funds,”) could all otherwise be used to pay for ODOT operations and maintenance—but instead they’re being used here to fund a capital construction project.

That’s not an isolated example: the agency uses lots of funds that can be applied to potholes and repairs to finance new construction. In the case of the Columbia River Crossing, millions for project planning came from federal “Interstate Maintenance Discretionary (IMD)” funds that can be used for the repair, repaving and upkeep of Interstate freeways throughout the state.

Here’s the thing: nothing stops ODOT from using “unanticipated revenue” or “savings” to pay for repairs. Even when the savings are in programs that are nominally dedicated to capital construction, the agency could use the savings to offset other capital construction costs paid from its more flexible funds, and shift those second-hand savings into repairs. But it doesn’t do so. Like sleight of hand in three-card monte, the budgetary legerdemain always works in the dealer’s favor.

Nothing new: A long-running con

Anyone who has followed ODOT for any period of time knows that these tactics are dog-eared pages in its playbook. Consider the two biggest projects the agency has pushed since 2000, the $360 million, five-mile long re-routing of US 20 between Corvallis and Newport, and the failed effort to build the $3 billion Columbia River Crossing. In both cases the agency used or proposed financial sleight-of-hand to come up with the needed money.

Pioneer Mountain-Eddyville US 20

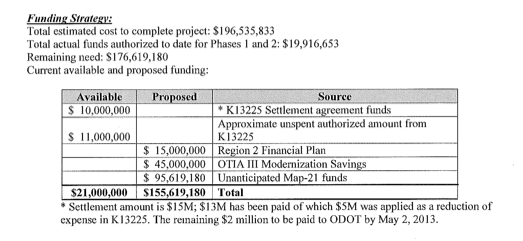

Originally, the Pioneer Mountain-Eddyville project was supposed to cost about $100 million, but through a prolonged serious of ODOT blunders, it ended up costing about $360 million. The agency found the money to pay for the cost-overruns from a combination of “savings” and “unanticipated revenue.” Here’s how they filled the last bit of the shortfall, according to ODOT’s own documents:

December 5, 2012 Memorandum from Matt Garrett to the Oregon Transportation Commission(US_20_PME_12_19_2012_OTC.pdf)

Most of the needed funds came from “unanticipated Map-21 funds,” with the balance coming from OTIA three modernization “savings”–OTIA 3 being a program to repair highway bridges. So when it wants to, ODOT manages to find money which could otherwise be used for maintenance and use it to cover the costs of capital construction.

The Columbia River Crossing

Consider the agency’s last proposed megaproject. In 2013, it sought legislative approval to go ahead with the $3 billion project, even though the state of Washington had pulled out—and taken its money and responsibility for covering half of all project costs with it. ODOT came to the Legislature asking for approval to incur debt for the project, and assured the Legislature that it had on hand all the money it needed to pay for Oregon’s share–initially $450 million, but with liability for vastly more–without the need to raise taxes. ODOT looked into its budget found “unanticipated revenue,” as reported by the Associated Press in its article “Bill proposes bridge debt but no funding source”

SALEM, Ore. (AP) — A bill approving a new Interstate 5 bridge over the Columbia River would authorize $450 million in bonds to pay for Oregon’s share, but it doesn’t say how the state would pay off the debt over the coming decades. Paying down the bridge debt would cost roughly $30 million per year. In the short term, the Oregon Department of Transportation can use unanticipated federal transportation dollars to cover the debt, lawmakers said. But after that money runs out in two to three years, the state would have to approve a new revenue source — such as a gas tax or vehicle fees — or reduce the amount of money available for other road projects. [Emphasis added].

Legislative leaders took ODOT’s word that there was money. House Speaker Tina Kotek’s spokesperson repeated ODOT assurances that the capital construction costs for the project could be paid out of ODOT’s existing revenue. Here’s Willamette Week, quoting Jared Mason-Gere of the speaker’s office in 2013:

“Speaker Kotek believes the committee structure this session allowed for a full and open consideration of the I-5 Bridge Replacement Project, while still moving swiftly enough to move the project forward. The committee considered the same elements of the bill the Ways and Means Committee would have, and worked closely with the Legislative Fiscal Office. The funding already exists in an agency budget. LFO has verified that the funds are available in the ODOT budget, and that they will not impact other existing projects. [Emphasis added].

So, when the agency wants to take on a huge mega-project, future budget considerations—even on the order of hundreds of millions of dollars which would directly reduce the agency’s ability to pay for future operations and maintenance—are no obstacle. Plus, in the case of the CRC (as with today’s Rose Quarter freeway widening and the Pioneer Mountain-Eddyville project) the revenue hit isn’t limited to the projected cost, but also includes a massive and undisclosed liability for cost overruns, which then directly impact operations and maintenance. The lack of budgetary flexibility to pay for operations and repairs today is a direct result of choices like this in the past to use or commit

Sell potholes, spend on megaprojects

If you’re a highway engineer, nothing is more boring that fixing potholes, and nothing is more glamorous than a giant new bridge or highway. While department leaders consistently swear that they’re committed to maintaining the system, whenever they get a chance, they either plan for giant projects for which they have no money, or low-ball the estimates on capital construction, knowing they’ll use their fiscal magic down the road.

The real giant, unfunded liability for ODOT is big new construction projects. The cost of the Rose Quarter project, which ODOT confidently told the Legislature would be just $450 million, has already ballooned to nearly $800 million, and could exceed a billion dollars if promised buildable covers are included. ODOT has said nothing about how these vast overruns would be paid for.

Meanwhile, ODOT is moving full speed ahead with plans for a revived Columbia River Crossing (now re-branded as “I-5 Bridge Replacement”). In its last iteration, the price tag for this project was north of $3 billion, and at this point ODOT has no money in its budget for its share of these costs. But it has allocated $9 million in planning funds to revive the project.

Paying Lip Service to maintenance, Paying interest on debt

ODOT officials talk a good game when it comes to the importance of maintenance. And while they apparently blame the Legislature for telling them to spend money on capital construction rather than fixing potholes, its sales pitch consisted of telling the public how much it cared about maintenance:

Here’s the agency’s current deputy director, Travis Brouwer, speaking to OPB, in April, 2017 as the Legislature was considering a giant road finance bill.:

Of course, patching potholes are far from the only thing ODOT has to spend money on. So how does the agency decide what to prioritize? According to ODOT assistant director Travis Brouwer, basic maintenance and preservation are a top priority.

“Oregonians have invested billions of dollars in the transportation system over generations and we need to keep that system in good working order,” he said. “Generally, we prioritize the basic fixing the system above the expansion of that system.”

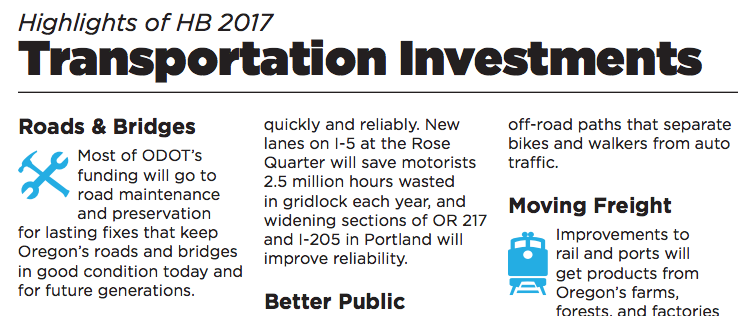

Back in 2017, the Oregon Department of Transportation put out a two-page “Fact Sheet” on the new transportation legislation. It’s first paragraph stressed that most of ODOT’s money would be for maintaining the existing system:

Generally, meaning, unless we decide to build shiny new projects—which they do. Make no mistake: When it comes to one of the agency’s pet mega-projects, there’s always money lying around, and if there isn’t, they’ll pretend like there is and charge full speed ahead, maxing out the credit cards to generate the cash.

In 2000, the agency was essentially debt-free. Since then, the share of State Highway Fund revenues spent on debt service has gone from 1 percent to more than 25 percent—and an increasing share of that debt burden is to pay off the costs of mega-projects. And, by definition, these debt obligations have first call on ODOT’s revenue, so the very act of debt-financing capital construction is a direct cause for the shortfall in funding for maintenance.

So, for example, look at recent decline in state gas tax revenues because of the decline in driving during the Covid-19 pandemic. The way ODOT has chosen to structure its finances, the budget shortfall lands disproportionately on operations and maintenance. The debt-cycle neatly provides a mechanism to implement a “bait and switch” strategy.

In three-card Monte, no matter which card you pick, ODOT will never have enough money for maintenance, but it will always be plowing money into big construction projects, and planning for even more.