Last Friday, President Trump signed an Executive Order effectively blocking entry to the US for nationals of seven countries—Iraq, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen. We’ll leave aside the fearful, xenophobic and anti-American aspects of this policy: others have addressed them far more eloquently than we can at City Observatory. And while there’s no question that the moral, ethical and constitutional problems with this order are more that sufficient to invalidate it, to these we’ll add an economic angle, which though secondary, is hardly minor.

America is a nation of immigrants, and its economy is propelled and activated by its openness to immigration and the new ideas and entrepreneurial energy that immigrants provide. Its commonplace to remind ourselves that many of the nation’s greatest thinkers and entrepreneurs, Andrew Carnegie, Albert Einstein, Andy Grove and hundreds of others, were immigrants, if not refugees. All six of America’s 2016 Nobel Laureates were immigrants. The fact that America stood as a beacon of freedom, and a haven from hate and oppression, has continually renewed and added to the nation’s talent and ideas. Immigration has also played a critical role in helping revitalize many previously depressed urban areas and neighborhoods. As Joel Mokyr explains in his terrific new book “A Culture of Growth,” the key factor triggering the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution was the ease with which heterodox and creative thinkers could find sanctuary in other countries and spread their thinking across borders. The US was founded on the kind of openness and tolerance than underpinned this process, and flourished accordingly.

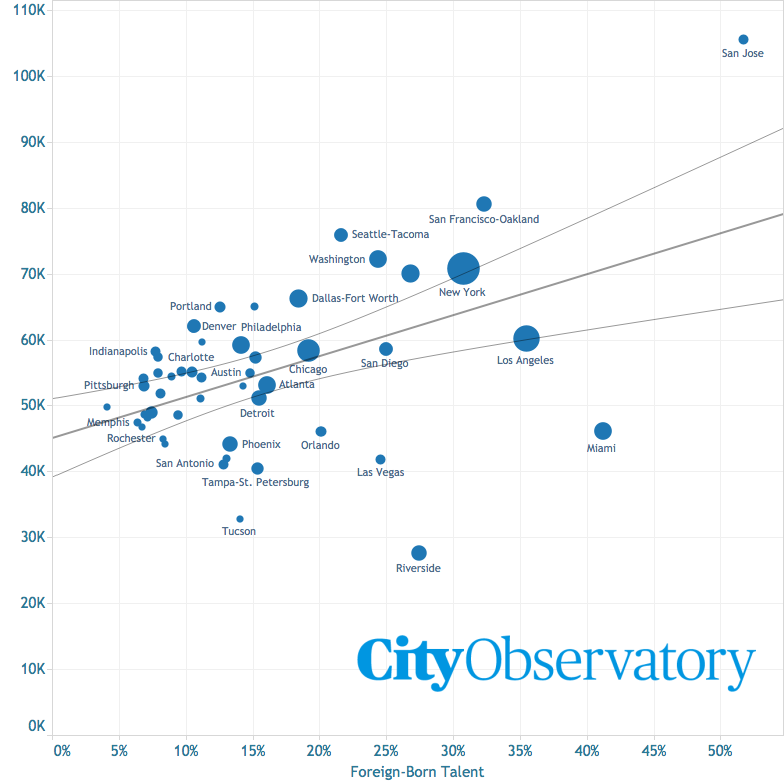

The critical role of immigration is abundantly clear when we look at the health and productivity of the nation’s urban economies. The metro areas with the highest fractions of foreign-born well-educated workers are among the nation’s most productive.

Metros with the most foreign born talent

Our benchmark for measuring foreign-born talent is to look at the proportion of a region’s college-educated population born outside the United States. We tap data from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, which tells us what share of those aged 25 and older who have at least a four-year college degree were born outside the United States. (This tabulation doesn’t distinguish between those who came to the US as children and were educated here, and those who may have immigrated to the US later in life as adults, but shows the gross effect of all immigration). In the typical large metropolitan area in the United States, about one in seven college educated adults was born outside the nation. And in some of our largest and most economically important metropolitan areas, the share is much higher: a majority of those with four-year or higher degrees in Silicon Valley are from elsewhere, as are a third of the best educated in New York, Los Angeles, and Miami.

Foreign born talent and productivity

We’ve plotted the relationship between the share of a metropolitan area’s college-educated population born outside the United States and its productivity, as measured by gross metropolitan product per capita. Gross metropolitan product is the regional analog of gross domestic product, the total value of goods and services produced, and is calculated by the Bureau of Economic Analysis. The sizes of the circles shown in this chart are proportional to the population of each of these metropolitan areas.

These data show a clear positive relationship between the presence of foreign-born talent and productivity. Several of the nation’s most productive metropolitan areas–San Jose, San Francisco, New York and Seattle–all have above average levels of foreign-born persons among their best educated.

Of course, these data represent only a correlation, and there are good reasons to believe that the arrows of causality run in both directions: more well-educated immigrants make an area more productive and more productive areas tend to attract (and retain) more talented immigrants. But it’s striking that some of the nation’s most vibrant economies, places that are at the forefront of generating the new ideas and technology that sustain US global economic leadership, are places that are open and welcoming to the best and brightest from around the world.

There are a lot of reasons to oppose President Trump’s ban on immigration from these Islamic countries. The most important reasons are moral, ethical and legal. But on top of them, there’s a strongly pragmatic, economic rationale as well: the health and dynamism of the US economy, and of the metropolitan areas that power the knowledge-driven sectors of that economy, depend critically on the openness to smart people from around the world.