There’s more evidence that housing market supply is beginning to catch up to demand in a way that is likely to moderate rent increases. Nothing, it seems, is more infuriating to those caught in a market of steady rent hikes that being lectured by some economist that what is needed to resolve the problem is an increase in supply. Nice to know, but that’s not going to pay the rent any time soon.

But just as after a long winter there are some early signs of spring, there are a few hopeful indicators from housing markets that the long promised relief from increased supply is starting to show up, at least in a small way. Today we look at two recent market reports, one national, and one quite local, that are beginning to indicate a market shift.

There’s no denying that rents in the US have escalated over the past several years. Overall rents are up 4.6 percent in the past year, and the national rental vacancy rate has plunged from more than 10 percent to about 7 percent, signaling that their are relatively more tenants bidding for every available apartment. As a result the share of households spending more than 30 percent of their income on housing has increased.

For the past several years—and for a variety of reasons—we’ve seen a surge in demand for rental properties. Some of that had to due, especially initially with the collapse of the housing bubble, and several million households being moved, quite involuntarily from the ownership market, into renting. At the same time, younger adults have been much more likely to rent that previous generations, and seem especially enamored of centrally located, walkable apartments in great urban environments. The net effect is that the demand for rental housing has risen steadily.

At City Observatory, we think there are two fundamental, and widely under-appreciated facts about housing markets. First, that when supply does catch up to demand, rent increases soften. Second, supply almost always moves much slower than demand. The supply of rental housing has responded only slowly; and has mostly struggled to keep up with increasing demand.

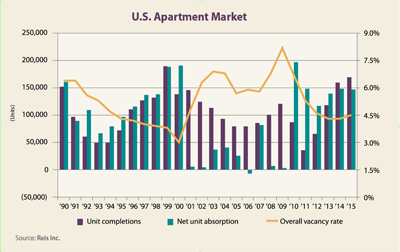

In the past few months there’s growing evidence that supply is starting to catch up. The market analysts at REIS follow national trends in apartment construction tracking delivery (the completion of new apartments) and absorption (how many newly completed apartments get leased. Absorption is a “net’ figure: the difference between the number of previously vacant apartments that get leased and the number of previously occupied apartments that become vacant over any time periods. The difference between the completions and absorptions drives vacancy rates. When lots more apartments get leased than new apartments are built, vacancy rates fall; when completions outpace absorptions, vacancy rates rise.

REIS tracks these numbers on an annual basis, and their estimates for the past three decades are shown here:

REIS analysts are reading the data to suggest that construction of new apartments is finally starting to have an impact on the market. REIS’s Scott Humphreys says: “It’s official: developers are finally building more apartments than there are renters to fill them.”

Similarly, at the blog Calculated Risk, Bill McBride reports on data from the National MultiFamily Housing Council (NMFC) which tracks vacancy rates for apartments around the country. Their data show that “market tightness” has been trending downwards for the past couple of years, and leads McBride to conclude that “it appears supply has caught up with demand—and I expect rent growth to slow.”

These data illustrate an important fact about supply and demand: Demand is highly volatile and can change quickly, while supply responds only slowly. Consider: the first decade of the 2000s was mostly a pretty bad time to be a landlord. A steady supply of new apartments was being built, but net absorptions fell short of the number of completions. In fact, at the height of the housing bubble, net absorptions were negative: more households moved out of apartments than moved in.

In the last two quarters of 2015, according to REIS data, completions outstripped net absorption by about 13,000 units in the third quarter and by nearly 15,000 units in the fourth quarter, with the result that the national vacancy rate ticked upward.

While national trends provide a helpful background, like politics, all housing is local. In an important sense, there really is no “national” apartment marketplace: apartments built in Cheyenne Wyoming really aren’t good substitutes for apartments in San Francisco. While there are broad national trends, the trajectory of supply and demand can play out differently in different local markets. The collapse of oil prices, for example, has dramatically altered the demand/supply balance in the oil patch town of Williston, ND, with the result that rents are off more than 20 percent from a year ago.

The evidence from one of the nation’s tightest housing markets, Boston, suggests that supply may be getting closer to catching up with growing demand. The Boston Globe reports that in the fourth quarter, rents in Boston increased by just one-tenth of one percent from the previous year, the smallest increase in five years. About 3,800 units came on line in 2015, and about another 5,000 are in the development pipeline. The news from Boston echoes reports from markets as diverse as Seattle, Denver, and Houston, that the growing number of new properties being completed is producing at least temporarily higher vacancy rates and more favorable rental offerings for tenants.

Nobody’s predicting a glut of unoccupied apartments—either in Boston, or nationally—that will push rents down. But slowly, and inexorably, the supply of housing is catching up to the demand, both in the aggregate and in the specific places where demand has grown most rapidly. It’s a reminder that if policy enables housing supply to expand, relief from higher rents can be delivered through the market.