Build expensive new “luxury” apartments, and wait a few decades

One of the most common refrains the the affordable housing discussion is “developers are targeting the high end of the market” and new apartments are just unaffordable. Left to its own devices, we’re told, there’s no way the market will build new housing affordable to the nation’s low and moderate income households. But the truth is that, with rare exceptions, the market has never built new housing for the bottom half of the income distribution.

In general, its the case that what affordable housing one finds today is housing that when it was first built, was occupied by people much higher up the income ladder. But as houses–and neighborhoods–age, they lose their market edge to new structures, and housing filters to progressively less affluent occupants.

This becomes clear when we take a longer-term perspective. Housing blogger Iain MacKenzie, who runs the definitive Next Portland website, tracking new housing and commercial developments in the Rose City, shared with us a couple of fascinating historical clips from the city’s paper of record, The Oregonian. They show that today’s affordable housing often started life as self-described “luxury” housing when it was originally built.

The first example dates back a half century, to the 1960s, when in the wake of urban renewal the city was building a wave of new apartments. The Oregonian of January 9, 1966 described the city’s booming market for new luxury accomodation:

“Luxury apartments, which start at $135 for a one bedroom unit and rapidly climb out of sight, have been sprouting in Portland at a breathless rate, and more are planned or abuilding. The total investment in such properties is certainly above the $100 million mark here.”

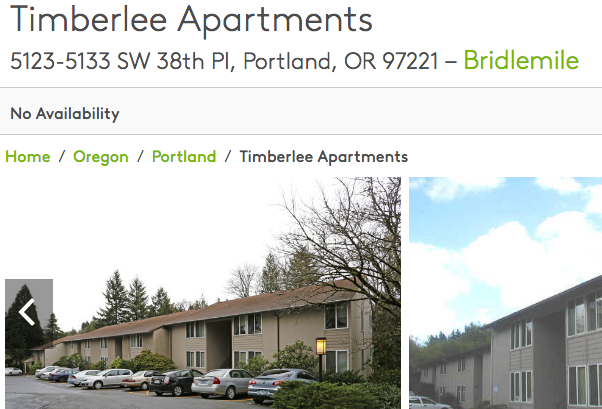

One of these complexes was the Timberlee in suburban Raleigh Hills, a close-in suburban neighborhood. According to the Oregonian, the Timberlee on SW 38th Place was one of the most prosperous of the 13 apartment complexes it examined in its story, with 97 percent of its 214 units rented.

Of course, the Timberlee Apartments are still around. While none of the units are currently for rent, according to Apartments.com, rents in the area run from about $1,000 for studios and one bedroom to $1,300 and more for two bedroom and larger apartments. By today’s standards, the Timberlee seems modest, and a bit dated, rather than luxurious.

The Timberlee apartments are typical of those that were built around the country in the 1960s and 1970s. As we’ve chronicled, similar vintage apartments in the Atlanta suburb of Marietta, started life as the preferred housing of (mostly white) young couples and singles, but as they aged, became so affordable that they constituted low income housing. The city spent $65 million of taxpayer money to buy and demolish these apartments, displacing hundreds of families.

Ian’s second clipping goes back just more than a century, to Christmas Day, 1910, when Portland was enjoying a small construction boom–interestingly, triggered by the advent of a tougher building code that would have made apartments more expensive or impossible to build in some neighborhoods. Just as with today’s inclusionary housing ordinance, there was a land rush as developers filed for building permits in advance of the deadline.

But back to our story. The 1910 article plays up the luxury of the new dwellings under construction.

The purpose of the builds is to establish a model for high-class apartments . . . The building will follow the latest style of construction in vogue in New York, and will embody the extreme of luxury with every possible attention given to comfort. Some new features in the way of modern conveniences will be introduced, the aim being to attract the desirable class of patrons, those who will be willing to pay as high as $150 a month for the five and six room apartments which they house will contain.

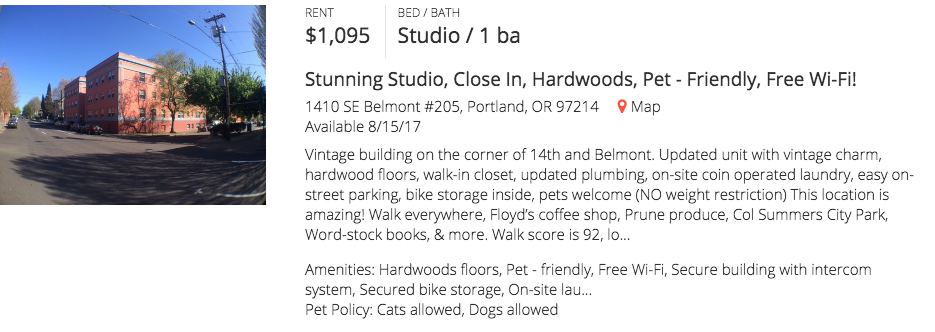

One of the new luxury apartment buildings constructed in 1910 was the Belmont Court, on the city’s growing East Side. Plans called for a modern 24 unit-apartment building with a range of conveniences.

Some fine dwellings of this class are being planned for the East Side. MacNaughton & Raymond have designed for E. L. Taylor a three-story brick veneer apartment-house 50×100, to be built at East Fifteenth and Belmont Streets and to cost $30,000. It will have seven three-room apartments on each floor and 24 in all, including the janitor’s quarters and two other suites in the basement.

More than a century later, the Belmont Court building still stands. In fact, two of its apartments are for rent just now. According to Zillow, average apartment rents in Portland are about $1,600 per month. With studio apartments renting at just under $1,100 they’re not exactly cheap, but they cost less per square foot than newly built units, and with a Walk Score of 92, there located in a neighborhood where one can conveniently live without a car.

Another interesting historical change. Described as three-room apartments when they were built, the Belmont Court apartments are today described as studios. They have a separate living area, kitchen and bathroom (each of which, a century ago, merited counting as a separate room). In an era when a large fraction of urban residents were boarders in boarding houses, a private kitchen and bathroom may indeed have been a luxury.

Here’s the takeway: New housing is almost always built for and sold to the high end of the marketplace. It was that way a hundred years ago and fifty years ago. But as it ages, housing depreciates and moves down market. The luxury apartments of two or three decades ago have lost most of their luster, and command relatively lower rents. And the truth is--that’s how we’ve always generated more affordable housing, through the process that economists call “filtering.” And the new self-styled “luxury” apartments we’re building today will be the affordable housing of 2040 and 2050 and later.

What causes affordability problems to arise is when we stop building new housing, or build it too slowly to cause aging housing to filter down-market. When new high priced housing doesn’t get built, demand doesn’t disappear, instead, those higher income households bid up the price of the existing housing stock, keeping it from becoming more affordable. Which is why otherwise prosaic 1,500 foot ranch houses in Santa Monica sell for a couple of million bucks, while physically similar 1950’s era homes in the rest of the country are either now highly affordable–or candidates for demolition.

Special thanks to Iain MacKenzie and NextPortland for their original research ideas and sharing these vintage news articles.