The Equality of Opportunity Project shows local factors matter, but even more for black kids

We now have a rich understanding of how where you grow up influences your life prospects. As we reported last week, the new Opportunity Atlas shows down to the neighborhood level, using big data gleaned from anonymized tax records, how where you grow up influences intergenerational economic mobility.

One of the big questions is what geographic scale these effects play out: Is it the state or region, the metropolitan area, the county, the neighborhood or the school?

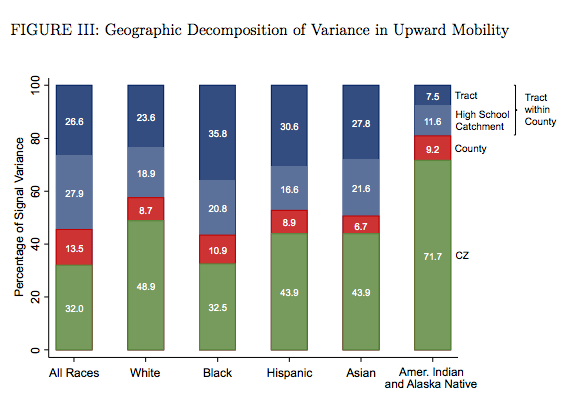

Raj Chetty, Nate Hendren and the researchers at the Equality of Opportunity Project have used their new, very detailed tract level estimates to estimate the contributions of different geographies to economic success. Essentially what they’ve done is to look to see how much more of the variation in individual outcomes is explained by looking at successively smaller geographies. So, for example, they look first at the variation in outcomes among “commuting zones”–large geographies that include metropolitan areas and surrounding rural counties.

Averaged across the whole US population, the variation in commuting zones explains about half of all the total variation in individual outcomes that’s attributable to geography. The other half comes from more localized effects–i.e. things that are different about the county you live in in the metro area, or your neighborhood or school district.

For black kids, the neighborhood you grow up in is even more important than your metro area

While on average, half of all variation is from these finer, neighborhood effects, there are important differences across racial and ethnic groups. The most striking outlier is black children. For black children, local neighborhood effects are even more important than larger regional ones. Compare, for example, black and white kids. For white kids, the commuting zone (metropolitan area) you grow up in determines about half (48.9 percent) of the geographic variation in your lifetime economic performance (local neighborhood factors make up the rest. For black kids, the commuting zone is far less important, making up less than a third (32.5 percent) of the variance. What seems to matter most is the characteristics of the local census tract and high school catchment area, which together make up more than 55 percent of the difference.

As we noted earlier, the latest report from the Equality of Opportunity Project makes it clear that neighborhood factors, like the poverty rate of your neighborhood, what fraction of your neighbors have finished college, and what fraction of nearby adults have regular employment, is a big contributor to intergenerational economic mobility. These highly localized factors seem to be even more important to the lifetime economic prospects of black kids.

The effects of poverty are highly localized

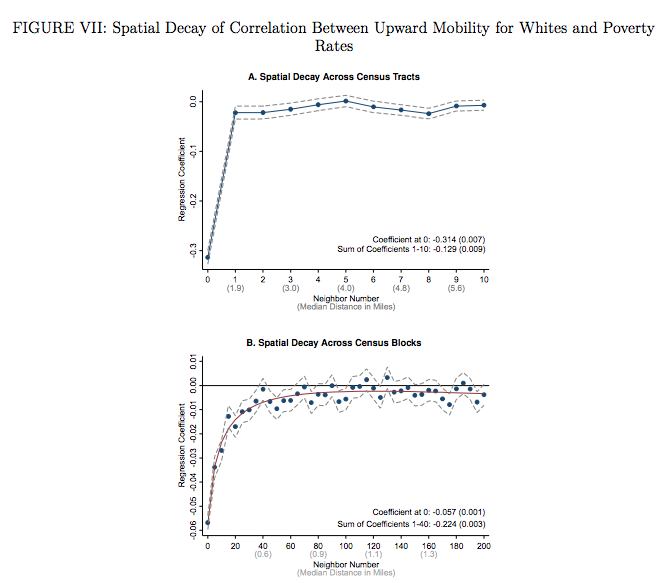

The authors dig deep into their data to try to better understand how the geography of poverty influenced children’s life outcomes. Which of your neighbors, in what physical area seem to have an impact on your prospects? Is it just those on your block or adjacent blocks, or do those who are further away have as great an impact. Using block level and tract level data, Chetty, Hendren, et al, compute a decay function (the rate at which the effect of neighborhood variables influences child outcomes declines with distance). The following charts show the impact of having neighbors with income below the poverty line on a child’s earnings as adults by the distance (in miles) from the place the child grew up. The negative numbers indicate that having neighbors living in poverty lowers adult income. This effect is relatively great for nearby households, but after 2 or 3 miles declines to almost zero.

Having poor neighbors nearby has a statistically significant negative effect on a child’s earnings as an adult. They conclude:

Having poor neighbors nearby has a statistically significant negative effect on a child’s earnings as an adult. They conclude:

In sum, neighborhood characteristics matter at a hyperlocal level. A child’s immediate surroundings – within about half a mile – are responsible for almost all of the association between children’s outcomes and neighborhood characteristics documented above.

The upshot of this work is a further confirmation that neighborhoods matter, and that if we’re serious about expanding opportunity for the poor, and especially poor children of color, breaking down the growing concentration of poverty in many of our urban neighborhoods has to be high on our agenda.

The Opportunity Atlas: Mapping the Childhood Roots of Social Mobility∗ Raj Chetty, Harvard University and NBER John N. Friedman, Brown University and NBER Nathaniel Hendren, Harvard University and NBER Maggie R. Jones, U.S. Census Bureau Sonya R. Porter, U.S. Census Bureau October 2018